Oh, God, I wouldn’t shut up about it. I was telling all my friends. I texted every doctor and health care worker I know. I was getting the COVID-19 vaccine tomorrow.

Since the spring, I’ve been volunteering at Prevention Point Philadelphia, a needle exchange and social services provider in the Kensington section of the city. I first learned of Prevention Point workers getting vaccinated for COVID-19 when I saw my boss there, Clayton Ruley, had posted to Instagram that he’d been vaccinated. Mainly, I was interested in telling him a joke about how now that I knew there were special vaccine stickers, I really wanted the vaccine. Ruley told me that as a volunteer I should be eligible for the vaccine, too. He gave me contact info for the city’s vaccination effort.

I emailed at 11:30 a.m. and had an initial response within the hour. I would receive the Moderna vaccine the next day at 3:20 p.m.

I spent the rest of the day talking to everyone I could. I told friends, I told sources, I cold-called people. I hadn't even received the shot yet, and yet I was blabbing about it all over. The first question was to find out: How, exactly, was I eligible for the vaccine? The city's health department clued me in.

The Pfizer vaccine began its rollout on Dec. 13. On Dec. 21, the Moderna vaccine began shipping. Vaccines are allocated to the CDC, which splits them up between the states and selected large cities with their own contracts with the government. Philadelphia is one of those cities.

Philly started getting its vaccines the week of Dec. 16. The city gave most of the vaccines to hospitals and left them to decide how to begin vaccinating its workers. But it held off a portion of the vaccines to give to health care workers not affiliated with hospitals.

One example is the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium. The group, founded in April, operates COVID-19 testing sites in Philadelphia’s black neighborhoods. Another is Prevention Point Philadelphia, where I volunteer.

“They've got high levels of exposure as well, but they're not really associated with a traditional health care model,” says Jim Garrow, the health department spokesman. “From our perspective, they're high risk. We want to make sure that we get them vaccinated, but we can't push them off to the hospital... That's why the city is running this kind of small clinic just again, for those targeted folks who have that high level of exposure. We want to get them vaccinated as soon as possible.”

Prevention Point executive director Jose Benitez told me they serve about 15,000 people; that means they have several hundred thousand interactions with clients a year. He advocated for Prevention Point to be included on this early vaccine rollout, and says about 70 people were vaccinated—with more on the schedule.

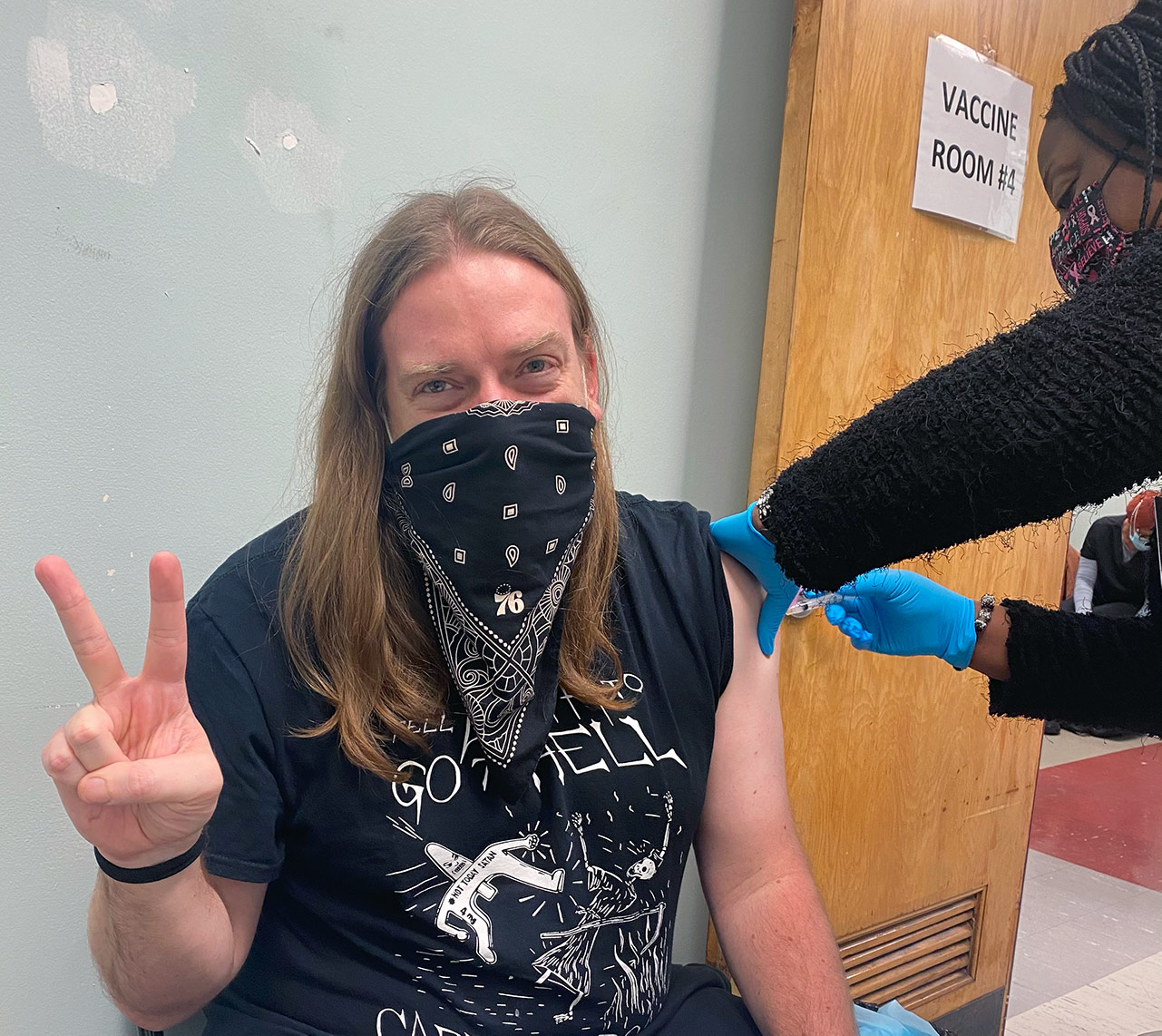

I was one of those 70. I put on a mask, tied a bandana around it, and went into the city clinic on the afternoon of New Year’s Eve. They took my temperature. I waited in a socially distant waiting room for a little bit. Workers in masks and face shields directed me to sign in, make an appointment for the second shot and, eventually, to a waiting room.

One worker checked me in, asked me some questions I do not remember, and we were off. It went quickly. And then it was over. I got my shot. It didn't hurt. The longest part of the experience was afterward, when I had to wait for a mandated 15 minutes to make sure I wasn’t experiencing any instant side effects. I talked with workers about sneakers for much of it. A timer went off and I was free.

Side effects were minimal. I was a little tired the next day, and that’s about it. My second dose is on Jan. 28. I do not plan to ease up on any of the precautions I've been taking in my daily life, but I do plan to keep volunteering at Prevention Point. For the pun alone, at least.

When I left the clinic, I felt great. But I also felt guilty. Why did I deserve to be one of the first 10 million people in the world to get the vaccine? Sure, there was an easy way for anyone in the area to do what I did: All they had to do was go back in time to the spring and start volunteering regularly at Prevention Point.

But there is a real problem with the vaccine rollout. The development of the vaccine—Pfizer and BioNTech’s, without U.S. Operation Warp Speed funding, and Moderna’s, with $1 billion of it—was an incredible technological breakthrough. A website from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia says that, on average, it takes 10-15 years for a vaccine to come out. It is unbelievable anyone received the vaccine before the end of 2020.

But the stated goal of Operation Warp Speed is to “produce and deliver 300 million doses of safe and effective vaccines with the initial doses available by January 2021.” We are at fewer than 5 million vaccine doses administered right now. The day before I got the vaccine, WHYY reported more than half the doses in Philly hadn’t yet been used.

On television Monday morning, the White House attempted to claim victory despite not vaccinating the 20 million people they said would be vaccinated by the end of the year. “What we said our goal was, was actually to have 20 million first doses available in the month of December. Those are available,” Health and Human Services secretary Alex Azar said on Monday. Even this technical parsing of language doesn’t quite make sense; there were only 13 million doses distributed through Saturday.

In Daytona, thousands of seniors waited in line overnight for their vaccine. Another line in Florida stretched for miles overnight, but only the first 600 people got vaccinated. Some doctors suggested giving just one dose of the vaccine, instead of two, in order to speed the process. (It's not just the U.S.; France only inoculated 500 people its first week.)

Some people have gotten the vaccine in stranger ways than I have. A man I know got it because his workplace received extra doses and they didn't want them to go to waste. A man shopping in a supermarket in Washington D.C. was asked by a pharmacist if he wanted to get the vaccine because they had leftover doses.

The good news, at least for people where I live, is that Philadelphia has planned ahead. A new Vaccine Advisory Committee, made up of 40 locals representing nonprofits, academic medical centers, and city officials will decide how things go moving forward. Garrow told me the city struggles with planning going forward due to uncertainty.

"It's tough for us to to sketch out exactly what's going to happen,” he says. “If, you know, lightning strikes, and a new president ramps up production and by the end of February a million doses roll into the city, then any planning we had for April and May doesn't make any sense. So when we developed our plan and submitted to the CDC this fall, none of it is really tied to timelines—it's tied to kind of a basic understanding of what we know is the phases and then like a buffet of choices, how you would go about vaccine [distribution] in this type of situation.”

The city expects to set up large vaccination clinics. It also expects to distribute the vaccines to pharmacists. Benitez told me that Prevention Point, which has done vaccinations in the past, hopes to offer its clients the opportunity to be vaccinated as more doses are made available.

As of yesterday, only 28,476 doses had been given out in Philadelphia. I no longer feel guilty about getting the vaccine—the ultimate goal is to vaccinate as many people as possible, and at this point the country is struggling to get its stockpiles into people's arms in a quick and orderly fashion—but I do feel lucky, and I wonder if I lucked into this because of the slow rollout, or in spite of it. Either way, the luck I feel is tinged with regret that I, or anyone else, needed to be lucky at all.