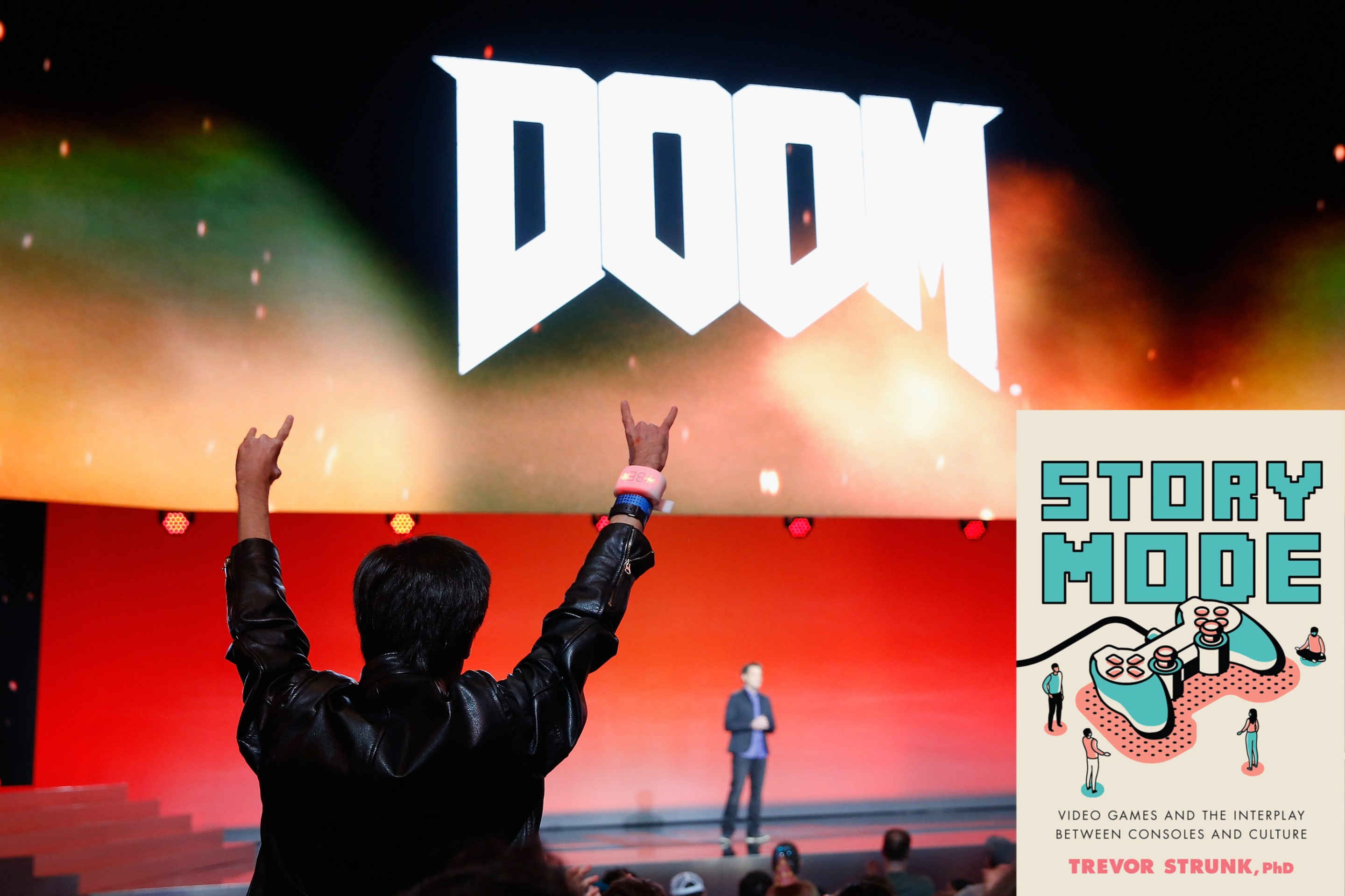

The following is an excerpt from Story Mode: Video Games and the Interplay Between Consoles and Culture, by Trevor Strunk. It's available for pre-order now.

It’s difficult to find reviews of DOOM that aren’t retrospectives. The game was as much a flashpoint for modern gaming when it was released in 1993 as any other game in history, and it arguably influenced the medium for American gamers more than any other. As a result, there is a preponderance of retrospectives on DOOM, but not many contemporary reviews that are available without a robust archival search.

Still, for DOOM this is fitting. This was a game that spread via nonconventional means, from newsgroup posts to shareware kiosks in the local Staples in my case, along with many other cash-poor eight- to ten-year-olds. The way shareware worked—for those readers not currently knocking at the grim reaper’s dusty door—is that you would buy an inexpensive floppy disc or, later, CD-ROM that contained a piece of a game on it. It was a bit like a demo disc before mass distribution and fast internet speeds made demos more plausible for modern releases. Shareware’s origin in the early 1980s is generally linked to three men: Andrew Fluegelman, Jim Knopf, and Bob Wallace created software (inter-PC communication, database management, and word processing, respectively) that they wanted to market in new ways. Vacillating among “freeware,” “user supported,” and “shareware,” the three men basically created the strange interstitial marketplace of free-but-not-without-strings software that we now know well as we search for, say, a flashlight or white noise app on our phones. Such a breakthrough in the market was fairly staggering for 1982, and Wallace noted on an episode of the television show Horizon2 that he came up with the idea through the influence of psychedelics (an early forbear of infamous drug-software conflationist and current quantum suicide victim John McAfee, perhaps).

But fantastic origin stories aside, it’s fair to describe the impact of shareware on the marketplace of early computer gaming as epochal: it leveled the playing field for distribution in a marketplace that, due to relatively less complex developmental tools than we have today, was already surprisingly level. This benefitted many companies, two of which we’ll spend some time with here: id Software, producers of DOOM, and Apogee Software, which produced the raucous violence-and-attitude drenched Duke Nukem 3D. Furthermore, the two companies worked together to produce 1992’s Wolfenstein 3D, generally considered to be the grandfather of the first-person shooter, or FPS genre, with John Carmack (who later helmed the development of DOOM) and Tom Hall of Commander Keen fame developing the game while Apogee published it. It perhaps says something about the small (if we’re being friendly; incestuous if we’re not) world of video game development that these two publishers were responsible for three of the most seminal FPS games in the genre, though id Software is the name most readily recognized for its development. Wolfenstein 3D and DOOM, released just a year apart, relied on the buzz and word of mouth that shareware promised.

To make the analysis about me for a moment (a terrible mistake in almost every situation): I was too young to get into Wolfenstein 3D, though I’d heard the same rumors every kid had: violent Nazi killing, robotic Hitler, and so on. But DOOM hit a sweet spot: an early 1990s environment in which the prevalence of family computers meant a lot of households had a floppy drive available from which kids, aided by the laissez-faire parenting of an America on the cusp of a financial boom, mainlined violent video games their parents wouldn’t necessarily approve of. The catch about shareware, though, is that the game developers absolutely want you to buy the full game, too. And so for me and many other players, DOOM was limited to only the first third of the game, with an ending sequence that left you on a cliff-hanger: the main character, Doomguy, had to descend into Hell itself to fight his way back to Earth. DOOM provided so much action and gratuity at the outset that it wasn’t really necessary to get more, not if you were too young or inexperienced to master the timing and patience needed in an FPS. Instead, the game existed, specterlike, on almost all of my friends’ computers in its half-finished form.

For the older crowd who did enjoy the full experience, however, DOOM was a monolithic network-destroying beast, slowing and crippling university networks that hurriedly banned the game before students connecting over Netplay for multiplayer player-versus-player (PVP) ruined campus internet networks. The absolutely essential David Kushner monograph Masters of Doom, which chronicles the history of the game, includes an excerpt describing the reception of the game at Microsoft headquarters as nearly religious; people reported spending sleepless nights playing DOOM with their friends. I could spend the entire chapter rehashing the cultural impact of the game hitting the adult gaming scene, particularly as concerns multiplayer, but the main takeaway is this: so popular was the game that widespread workplace and campus rules had to be put in place to save the network capacities of these early internet connections. Productivity was unsalvageable.

Of course, the game that was ruining workplace productivity and infrastructure wasn’t innocent Tetris or the nationalistic Wolfenstein 3D—it was a game in which an ultraviolent marine gleefully murdered demons on a satanic Mars. Pentagrams, blood and guts, and quippy lighthearted riffs on the life and death of people, zombies, and monsters were plentiful. id Software’s loose sense of social propriety fueled this with an initial swastika-shaped level as a “tribute” to Wolfenstein 3D, which was later removed, as well as a difficulty selection screen that included the options (from easiest to hardest) “I’m Too Young to Die,” “Hey, Not Too Rough,” “Hurt Me Plenty,” “Ultra-Violence,” and “Nightmare.” The first episode of DOOM, the one that my friends and I played again and again, was called “Knee-Deep in the Dead.” The game did not shy away from the violent elements it presented and in fact revelled in them, which encouraged its famously robust mapmaking fanbase to continue the aesthetic of difficulty and gore in many self-made maps distributed free with id’s blessing.

Of course, I’d be remiss in not mentioning the most infamous DOOM mapmaker, Eric Harris, one of the two boys who committed mass murder at Columbine High School in 1999. In a video he made, Harris claimed that the Columbine shooting would be just like DOOM and that the shotgun he had was straight out of the game. Harris’s DOOM maps are rather typical entries in the genre, not particularly interesting in any way, which makes them troubling for parents searching for some sort of reason after the fact and seeking to blame the game. It’s no surprise that six years after its release, DOOM, which had garnered a reputation as a fairly over-the-top game, was being hailed as the step too far that games had been trying to avoid since their inception. David Grossman, for Accuracy in Media, said the game was “a mass murder simulator,” and the implicit fear that this simulation is what lead Klebold and Harris down the path to a violent reality set in quickly and solidified even more quickly. Indeed, infamous lawyer-cum–culture warrior Jack Thompson had filed a suit in 1997 alleging that Wolfenstein, DOOM, and pornography had led to a different school shooting by a boy named Michael Carneal. The suit sought $33 million in damages and was dismissed quickly, but the germ of the idea was there: the games that these kids all played were similar and so must have impacted their behavior.

The idea isn’t totally out of left field, but—particularly in the case of DOOM—it ignores the massive popularity of the game in favor of a narrative that depicts it as somehow niche and dangerous. As I’ve intimated above, you’d be hard-pressed to find a kid who liked video games who hadn’t played DOOM or DOOM 2 by 1999. Furthermore, the violence in DOOM and, particularly, in its successor from Apogee Software, Duke Nukem 3D, was sophomoric and rude but primarily drew from the tradition of the schlocky horror comedy of the early 1990s. Duke Nukem 3D lifts lines from Rowdy Roddy Piper’s commanding role in John Carpenter’s They Live, growling, “It’s time to kick ass and chew bubble gum. And I’m all out of bubble gum.” Meanwhile the aggressively goofy quality of the violence in DOOM recalls Sam Raimi’s 1992 film Army of Darkness far more than Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò. The jokes are often sexist, ableist, and in poor taste, but they are jokes you’d expect from the shock jocks of the early to mid-1990s, a period that gave us the warmed-over Airplane! retread of the Scary Movie franchise.

Ultimately, the blood and gore of DOOM as well as the satanic imagery therein was transformed by Klebold and Harris into something that was viewed as darker and with a clearly violent, antisocial intent. It is easy in 2021 to scoff at this and associate DOOM’s jokey schtick with the kind of eye-rolling apologia reserved for early 1990s comedy films. But in the moment, society was desperate for some sort of explanation for how two kids could snap and kill a dozen classmates. And the FPS genre, installed on untold numbers of school computers along with more refined successors such as Quake, was an easy target and indeed a specifically named influence on these school shootings.

If DOOM cocreator John Romero hadn’t shot himself in the foot by claiming that his 2000 game and famous critical flop Daikatana was “going to make you [his] bitch” in wide-ranging ads in almost every video game publication, we might have a fascinating history of id Software fighting its persistent reputation as purveyors of murder, death, and aberrant social behavior. As it stands, the twin forces of Daikatana and the twelve-years-delayed Duke Nukem Forever made id Software and Apogee (now 3DRealms) afterthoughts throughout most of the 2000s. Although the impact of these games never abated—for DOOM, the fan community remains strong and now is able to play and trade their maps over far more stable and speedy internet connections—FPS games veer away from its schlocky and fun forebears in the year 2000 and beyond. Some games like Painkiller and Blood, not to mention console greats like Goldeneye and Perfect Dark for Nintendo 64, retained the basic genre premises of 1) first-person perspective and 2) gun held slightly above waist level, blasting anything that moved. And Halo wore its influences on the early days of first-person shooters on its sleeve.

But by the early 2000s, we were seeing fewer games like DOOM that dealt in the fantasia of ultraviolence and more games that tried to replicate the everyday violence of military encounters. The cultural tide had turned away from DOOM, controversy and all. What is less clear is at what specific point that tide turned. It’s plausible to say that post-Columbine, FPS games began to change the way they embodied violence, swapping out blood and guts for more nuanced or tactical encounters. Or perhaps 9/11 marked the turning point, since FPS games next evolved into the military shooters we now associate with the genre.

Suffice it to say that between 1999 and 2002, all of the most important and defining FPS series for the next decade released their first installments, and all of these games were pointedly not like DOOM. Part of this had to do with the rise of Sony’s Playstation 2 and Microsoft’s XBox and the way that they made 3D combat more aesthetically pleasing and more viable for multiplayer, the prioritization of which changed the mechanics and aesthetics of the genre. But a much larger part, I suspect, had to do with heightened concerns over the cartoonish and hyperviolent DOOM style of shooter, as well as a feeling of heightened paranoia and wounded American exceptionalism in the wake of 9/11.

The first of these series, at least, could have been motivated by the former, even if it missed 9/11 by the skin of its teeth: Medal of Honor, the highly realistic World War II military shooter, was released in October 1999. The war game genre was by no means new and had dominated the simulation game scene for years at this point. But there was something more action based and less tactical about Medal of Honor that was new; this was certainly a game marketed to the same history buffs who would play, for example, the Sid Meier simulations of historical sea battles in Pirates! but, simultaneously, the game found an audience in the same demographic of players that so enjoyed DOOM six years earlier. In his review for Next Generation, Jeff Lundrigan explains the success of the game, saying that “few things are more satisfying than shooting a Nazi in the face,” and this more nationalistic reasoning certainly enabled the game to escape, for the most part, the intense scrutiny of moral groups after Columbine.

However, this deference to the non-DOOM FPS games should not be written off as time-and-place specific explanations. Even in its more recent iterations, the DOOM franchise has been a lightning rod for cultural panic. DOOM (2016) got this write-up in Common Sense Media, an infamous media guide for parents: “Creatures are not only blown apart, they’re also torn apart by the hero. There’s a steady stream of blood and gore, as well as lots of satanic imagery. Such curse words as ‘f--k’ and ‘s--t’ are uttered by different characters. Our hero is also oddly abusive and needlessly smacks droids who’ve just handed him a weapon upgrade.” On the other hand, Medal of Honor’s 2010 release was reviewed with some hesitancy, as “an extremely realistic, intense, and violent military game that takes place in modern-day Afghanistan, a setting that might bother some families, particularly those with members currently enlisted in the armed forces.”

The difference between Common Sense Media’s reviews here is subtle in terms of wording but comes through clearly: DOOM (2016) is violent in the bad way; Medal of Honor (2010) is violent in the often troubling but ultimately necessary “good” way. Especially after Electronic Arts “recently took out the option to play as the Taliban in the online head-to-head mode.” The accolades heaped upon Medal of Honor (1999) rely on this equivocation, because a heralded game wherein the entire purpose is to make Swiss cheese of other human beings on a war-torn battlefield only can be heralded if it is also “necessary.” A reminder of history—of how good it can feel to shoot a Nazi, if properly labeled as a Nazi, on a battlefield in 1944 in Normandy—is what the FPS genre needed to elude the third rail of Columbine. The mood in America after 9/11 certainly helped move this mindset along. Battlefield 1942 (2002) and Call of Duty (2003) were both World War II FPS simulators that launched enormously popular franchises, both of which still exist as of this writing.

Meanwhile, Tom Clancy’s incredibly popular Rainbow Six series continued apace for third-person games that could be brought in under the umbrella of “patriotically acceptable violence against others.” The reviews of these games once again tell the tale of the moment far better than I could and were possible only in their sedimented and entirely un-self-conscious patriotic semiotics in the strange hyper-reactionary moment in America after 9/11. The editors of Computer Games Magazine ranked Call of Duty the sixth best computer game of 2003, saying, “This game ups the ante in the WWII shooter arena, and makes everything that has come before it seem as outdated as France’s army.” The shot at France of course mirrored the then-current discourse surrounding its refusal to aid America’s war against Iraq and the frequent legislation attempting to rename french fries “freedom fries.”

Meanwhile, Battlefield: 1942 was described by the same magazine, one year earlier, as “a near-perfect balance between fun and realism.” It’s important to take a moment here to pause before rushing through the greatest hits of these franchises, particularly Call of Duty, which has become one of the fabled “too big to fail” game franchises that define yearly release schedules, as the question that goes unasked in these reviews is, when did the idea of realism in these shooters become something to be desired? Jack Thompson, who attempted to link DOOM to school shootings, continued to castigate violent video games. But although he’s attacked games like Grand Theft Auto or Halo or—the closest analogue to any of the patriotic FPS genre discussed here, the terrorists-versus-operatives fan-made success Counter-Strike—he seemingly does not worry overmuch about Call of Duty or Battlefield or Medal of Honor. One of Thompson’s most aggressive complaints against Rockstar Games’s Grand Theft Auto franchise is that it allows you to kill police officers—virtually, in a game that is not real. He even has attempted to elicit the help of police officers in his quest against the franchise, albeit with limited support.

That said, Thompson has a long history of pro-police litigation, even as the domino that tipped Ice-T and Body Count’s termination from their contract agreement with their label Time-Warner Studios for their song “Cop Killer.” To make it clear that this whole police/military thing is a blind spot, this is a man who tried to ban an evangelical Left Behind game, saying the violence in the game was unacceptable due to its affiliation with Christianity. Thompson’s targets are the outliers, the purposefully provocative, and yes, at times, the offensive or obscene. But those targets were never the military or the police. Even as the Call of Duty franchise evolved to include more adult, contemporary themes such as torture or, in a recent release, the ability to drop white phosphorus on enemies, it received criticism from some players who argued that “the White Phosphorus killstreak perk . . . provides no context and does not effectively convey how horrible such a weapon is” but was met with unconcerned silence from most everyone else.

Meanwhile, the popular gaming press of the early 2000s, primarily gaming webcomics that had become enormously popular like Mike Krahulik and Jerry Holkins’s Penny Arcade and Tim Buckley’s Ctrl+Alt+Del, made Thompson a celebrity of sorts, producing comics that still get posted every so often in which the characters break the fourth wall and solemnly lecture Thompson on the fact that games do not make people violent and that gamers are very good people, just do not push us any further, Mr. Thompson. It’s all very earnest and silly, but there is something alarming about the lack of critical vision here. The goal, seemingly, is to refute Thompson’s admittedly nonsensical attempts to tie real-world violence, in terms of an active causal relationship, to video games. In effect, though, Thompson’s critics simply perform the same sort of essentialism, arguing that no representation of violence in a video game is bad. This has led to a blind spot that explains why we see no substantive critique of the war crimes and brutality of the mainstream FPS series of the moment. Even the critiques of Halo and Counter-Strike feel weak compared to the full-court press against the now-primitive-looking DOOM.

The defense of games by the Thompson critics essentially whitewashed any decision by any company in the future vis-à-vis violent or extreme representation. It is carte blanche to produce whatever content desired with the guarantee that the players of the games will not revolt against the games based on content alone but instead on some mixture of content and execution. In essence, it is the direct opposite impact of Thompson’s attempted bans, and it obscures the more obvious blind spot that Thompson, gamers, and any of the morally outraged parent groups had regarding earlier FPS games: that if you include the military, specifically the U.S. military, violence is not only sanctioned, but often considered solemn, necessary, even profound. And if the more metaphorical sanctioning of military violence in video games doesn’t resonate, consider that in 2002, the U.S. military released its own game, America’s Army, which was literally and openly intended as a recruitment tool.

Free to all, the game was, according to its own FAQ, meant to show “the whole world . . . how great the U.S. Army is.” During an interview with GameSpot, Casey Wardynski, the officer who conceived of the game in 1999, says that he is “a research PhD. I run an analytic cell here at West Point and most of our analysis is on labor economics, and, for example, incentive structures.” Wardynski doesn’t see any real relevance between this specialization and the free game he has spearheaded that lets kids have fun with their friends and is licensed and controlled by the U.S. Army, so we can take him at his word, of course. GameSpot, for its part, pushes back on Wardynski almost not at all, the closest they come being: “Do you still come across the question that asks if there is a disconnect between the entertainment value of America’s Army and the sometimes, maybe oftentimes, grim reality of the real world battlefield?” Wardynski’s answer? “You can’t escape the central point, which is armies are built to employ force.”

Wardynski is right, of course, but this is meant to mesh with his argument that the game supports the “volunteer army” of the United States. Wardynski is a recruiter here first and foremost, and to paraphrase an old joke, the way you know that recruiters are lying is if you can see their lips moving. But the controversy around this game was limited to academics like David Nieborg who were appalled by the obvious propaganda of a free video game made by the army telling players what the “army is really like.” Punk rock group Propaghandi included a song on its 2005 record Potemkin City Limits called “America’s Army (Die Jugend Marschiert)” that critiqued the game by comparing Wardynski to a Hitler Youth spokesperson. Games artist Joseph DeLappe attempted to subvert the multiplayer in America’s Army to critique the illegal war in Iraq by posting the names of soldiers and the dates they were killed in chat for a project called “dead-in-iraq.” Based on the documentation on his website, the response to the project was one part bemused confusion and another part “lol.”

Suffice it to say, America’s Army did not receive the same opprobrium reserved for DOOM or Grand Theft Auto, despite being a literal attempt to encourage kids to create material death and destruction in an organization built to employ force. In fact, Jerry Holkins of Penny Arcade said this about the franchise: “These America’s Army games really seem to enrage some people. I have it under good authority that [my wife’s] not crazy about them either. That’s fine, you can all be wrong together.” This is, of course, the same Holkins who was so aggrieved by Jack Thompson’s rage against games that he and his co-creator donated $10,000 to charity in order to show him up. Kudos for the donation, of course, but the inability to connect the fact that the army is banking on precisely the same logic as Thompson in order to enlist kids helped to preserve the massive smokescreen that military shooters would provide for overt militarism and propaganda in the years to come.