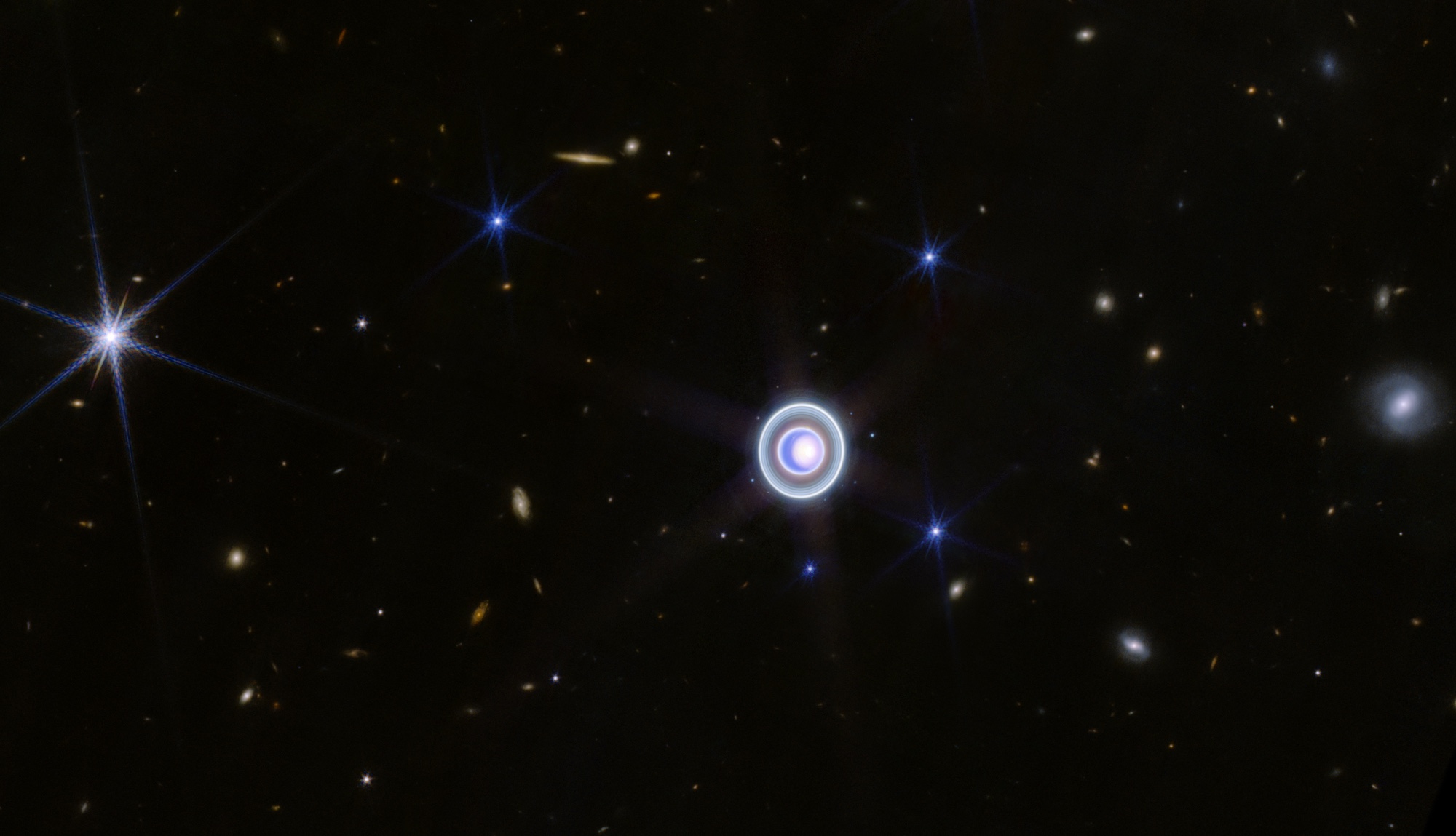

Not all science has to, you know, advance science. Sure, Webb is constantly discovering all sorts of neat things about our universe. But sometimes NASA decides to point its $10,000,000,000 space telescope at shiny things just because they know it'd make a good photo. And they're right! Here's Uranus, our oddball seventh planet, aglow in the black like the solar system's most intense Christmas light. And if Here's a cool picture of Uranus is a good enough justification for NASA, it's good enough for me.

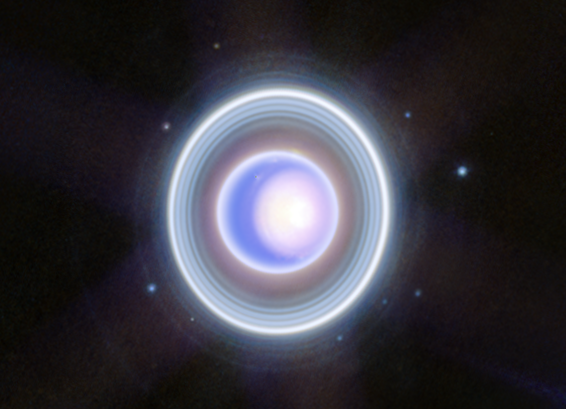

In the image released today, a closeup of which is below, we're looking down at Uranus and 14 of its 27 moons from above its northern hemisphere. Uranus has an axial tilt of more than 90 degrees, believed to be because it took a hit from another protoplanet in the solar system's early days. This means we get good end-on looks at its 13 ring systems, which itself are pretty unique: they're notably younger than Uranus itself and did not form with the planet, leading to speculation that they were once a moon or moons that were destroyed by impacts.

We're seeing Uranus here from Webb's Near-Infrared Camera, which is why it looks so different from the only close-up, true-color images we have of it, from Voyager 2's visit in 1986. In those, Neptune appears a pale, placid cyan—frankly, our most soothing planet to look at. Here, though it looks active, more accurately reflecting Uranus's actual dynamism. Its seasonal polar cap is visible; further south, storms wrack its atmosphere; its many moons swarm, some even within the rings. The planet's rotation is fast, with a day only lasting about 17 hours, so this image is actually a composite of several Webb snaps—Uranus is too alive and moves too quickly to pose for photos with exposure time of longer than a few minutes.

Uranus is an ice giant, a slightly misleading term that refers to the heavier, more volatile elements that make up it and Neptune, as opposed to the primarily hydrogen-and-helium gas giants Jupiter and Saturn. There's very little ice there: it's mostly gas and liquid, a steamy, goopy, and very cold morass of water, ammonia, and methane. We couldn't land on Uranus because there's nothing to land on, and anything that tried would be rapidly destroyed by the extreme temperature (−371.5 °F has been recorded) and crushing pressure. Uranus is still a pretty big mystery for something so close by; we still don't even have a model that satisfactorily explains how ice giants form.

Scientists very badly want to learn more. In the most recent Planetary Science Decadal Survey, basically a NASA wish list, a Uranus Orbiter and Probe was given the highest priority by respondents. It's been nearly four decades since Voyager 2 made a high-speed flyby within about 50,000 miles of Uranus, and much of its atmosphere was concealed by a haze at the time. But even that unsatisfyingly brief visit revealed 11 new moons, two new rings, and a misaligned magnetic field. Imagine what we might learn from an orbiter that spent up to five years investigating Uranus, and would make multiple close flybys of its major moons, some of which have been speculated to have liquid water oceans. We'll have to wait a while. NASA is currently eyeballing a launch in the mid-to-late 2030s, with arrival around Uranus some 14 years later.

So we'll have to make do with pictures for now. It's a rare treat that Webb even turned its eye on our own solar system in the first place, as it's really designed for ultra-distant objects, whose high redshift means their emissions appear in the infrared. It's why Webb is in many ways better suited to teach us about exoplanets than our own neighbors. But, again, sometimes a cool image is reason enough.