If 2023 began as the year of the Cocaine Bear, Elizabeth Banks's magnum opus about a bear on a coke-fueled rampage, it ended as the year of the Cocaine Shark, thanks to the low-budget horror flick Cocaine Shark and the unrelated Shark Week documentary Cocaine Sharks. The documentary intended to investigate rumors that swirled for decades, suggesting that sharks might have dabbled in the blocks of cocaine that frequently litter Florida's coasts; just last month, 65 pounds of cocaine washed up on a beach in northern Florida. Cocaine Sharks dared to ask the question: Would the Sunshine State's abundant marine life really let all that cocaine go to waste?

It's not that sharks are particularly inclined toward snorting a gill-full of cocaine, but Cocaine Corals or Cocaine Jellyfish confer none of the danger or intrigue as a shark on stimulants. The documentary team dumped packages designed to resemble cocaine bales into the ocean to see if sharks would bite. Some did. And though the team did not actually offer the sharks a bump of real cocaine, they offered the predators a bait ball of highly concentrated fish powder intended to trigger a similar dopamine rush, according to Live Science. The sharks went wild. "I think we have got a potential scenario of what it may look like if you gave sharks cocaine," Tom "The Blowfish" Hird, a marine biologist said in the documentary. "We gave them what I think is the next best thing."

It bears (sharks?) mentioning that Shark Week and its descendants are not known for scientific rigor, and often spread junk science and misinformation. Scientists do not know how a shark would react to cocaine, and giving a shiver of sharks a sack brimming with fish powder seems like a very accurate way to test if sharks like fish powder, but a less accurate way to test if sharks like cocaine.

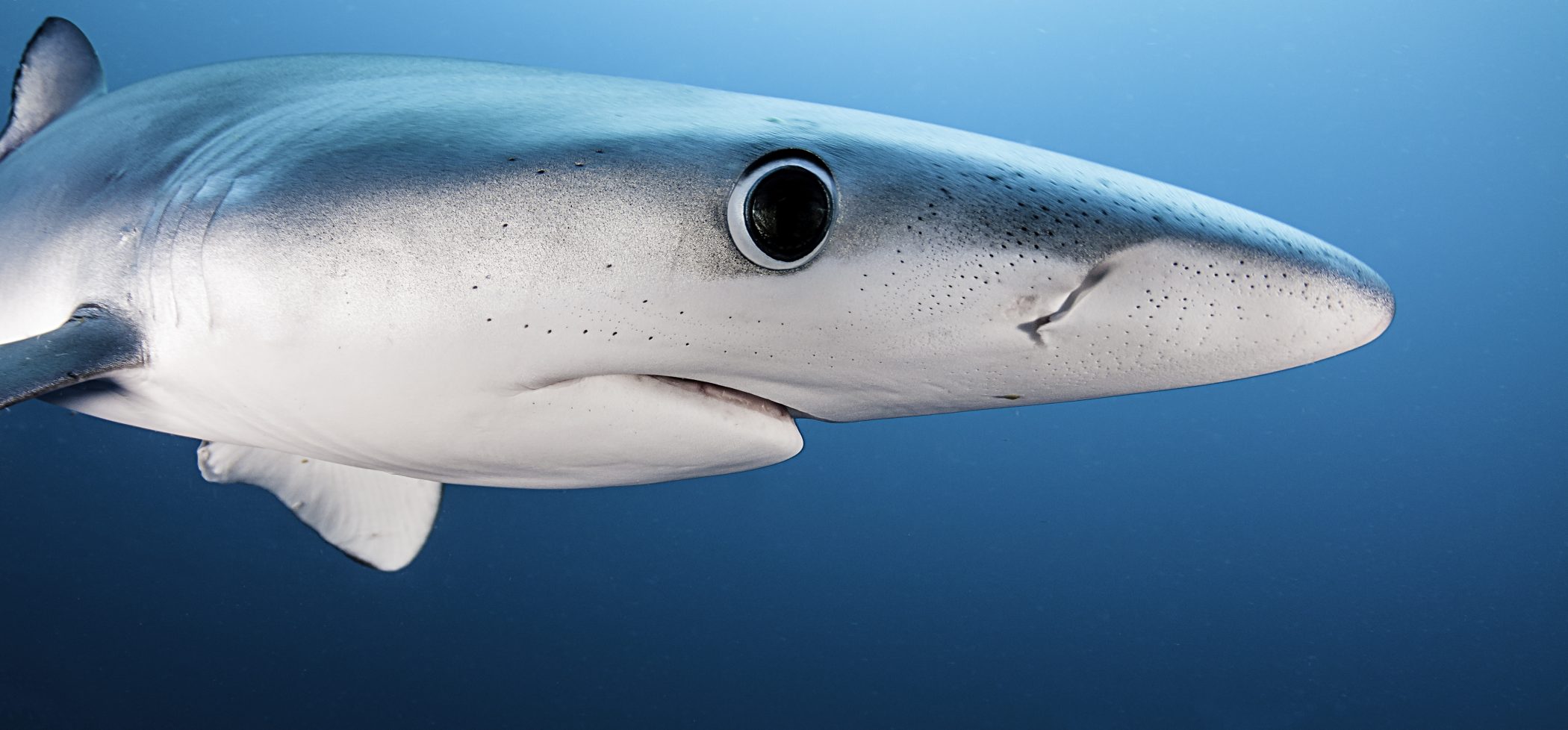

Tragically, Cocaine Sharks did not uncover any evidence of sharks actually ingesting cocaine or any traces of the illicit drug in the system of any fish. But this month, scientists in Brazil finally tracked down some sharks that happened to be on cocaine and reported their findings in Science of the Total Environment. Specifically, they found traces of cocaine in the muscle and livers of 13 Brazilian sharpnose sharks found near the coast of Rio de Janeiro. The news spawned sensationalist headlines about seas "infested with 'Cocaine Sharks,'" giving people yet another dubious reason to fear the cartilaginous fish (or declare they, too, were having a brat summer).

In some ways, sharks are late to the party. The elasmobranchs are far from the first wild creatures to be hopped up on illicit drugs. In 1985, the 175-pound bear that would later become Elizabeth Banks's muse discovered cocaine dumped by a parachuting smuggler and immediately died of an overdose. But now, many populations of wildlife around the world are constantly exposed to cocaine and other illicit drugs in a haunting, ceaseless party that is, at best, making them feel a little weird, and at worst, actively harming them.

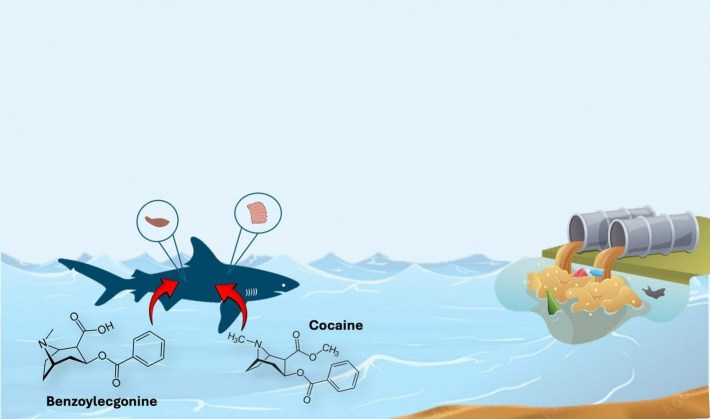

Although Cocaine Sharks suggested a shark's primary means of accessing cocaine would be something as cinematic as tearing into smugglers' freshly jettisoned bales of product, the reality is both more underwhelming and deeply worrying: Most wild animals are exposed to cocaine via our wastewater. When people use cocaine or other drugs, their urine and feces douse sewage with pharmaceutical traces. And most of the world's wastewater treatment plants are not designed to completely remove the byproducts of drugs like cocaine or meth, resulting in drug-tainted wastewater entering local aquatic ecosystems. This is a problem around the world, from the Thames and Arno Rivers in Europe to the waters off the Brazilian coast.

It's unsurprising that anything living in a river or ocean tainted by wastewater would get some pharmaceutical swill in their system. The first big study to this effect was published in 2009, when researchers found a trickling sludge of meth, ecstasy, cocaine, and other illicit drugs in rivers in Nebraska. When scientists conducted laboratory tests to determine what cocaine did to various species, they found a slew of harmful effects. Brown mussels exposed to cocaine had elevated levels of dopamine and serotonin, which could affect their reproductive system. Zebrafish had reduced cell viability and fragmented DNA.

One experiment exposed critically endangered European eels, which move from freshwater to the ocean over the course of their complicated lives, to the same amount of cocaine found in some rivers. The eels' muscles swelled and even broke down, and they experienced increased levels of the stress hormone cortisol, which could delay the eel's ability to bulk up before migrating to the Sargasso Sea to breed. Eels living in rivers near England's Glastonbury Festival are immediately doused with ecstasy and cocaine when the festival concludes.

It's still unclear what effects cocaine might have on sharks, but one imagines that none of them are good. The new paper only collected data from 13 sharpnose sharks sourced from small fishing vessels, meaning they never got a chance to observe their behavior in the wild. But the researchers found the sharks had about three times higher levels of cocaine than benzoylecgonine, its primary metabolite. This suggested the sharks might have ingested cocaine that had not already passed through a human body, but was instead dumped directly into the water or drained from an illegal refining lab. The extreme levels of cocaine found in the sharks' bodies might also be related to their position on the food chain, similar to how tunas bioaccumulate high levels of mercury: Cocaine Shark may have only become possible because of thousands of nameless Cocaine Fish, each of whose life story could spawn a hit movie in a never-ending franchise.

Correction (11:38 a.m. ET): An earlier version of this story incorrectly referred to Cocaine Bear as Elizabeth Banks’s directorial debut. We apologize to Pitch Perfect 2.