The first time I saw Blanche DuBois, she was just words on a page. I was a teenager with somewhat sophisticated reading tastes, and so I'd bought a skinny paperback copy of the Tennessee Williams play A Streetcar Named Desire. I moved through it quickly and at least partially recognized its greatness, but I was almost entirely focused on the character of Stanley Kowalski. Someone just reading the script of a play has to create a "performance" almost entirely with their mind, but Stanley helps you out plenty. He's blunt, harsh, dominant. In contrast with Blanche, whose inefficient dialogue hovers around the edges of what she means, Stanley creates a forceful impression.

STANLEY:

What does it cost for a string of fur-pieces like that?

BLANCHE:

Why, those were a tribute from an admirer of mine!

STANLEY:

He must have had a lot of—admiration!

BLANCHE:

Oh, in my youth I excited some admiration. But look at me now!

[She smiles at him radiantly]

Would you think it possible that I was once considered to be—attractive?

STANLEY:

Your looks are okay.

BLANCHE:

I was fishing for a compliment, Stanley.

STANLEY:

I don't go in for that stuff.

BLANCHE:

What—stuff?

STANLEY:

Compliments to women about their looks. I never met a woman that didn't know if she was good-looking or not without being told, and some of them give themselves credit for more than they've got. I once went out with a doll who said to me, "I am the glamorous type, I am the glamorous type!" I said, "So what?"

BLANCHE:

And what did she say then?

STANLEY:

She didn't say nothing. That shut her up like a clam.

I think, also, that a teenager is an especially harsh audience for Blanche. In that early stage of life, aging is a future you want to experience, not a process to dread. In my introduction to the character, I was very unkind. I thought she was weak and delusional and ultimately pathetic—a grown woman who just couldn't hack the world.

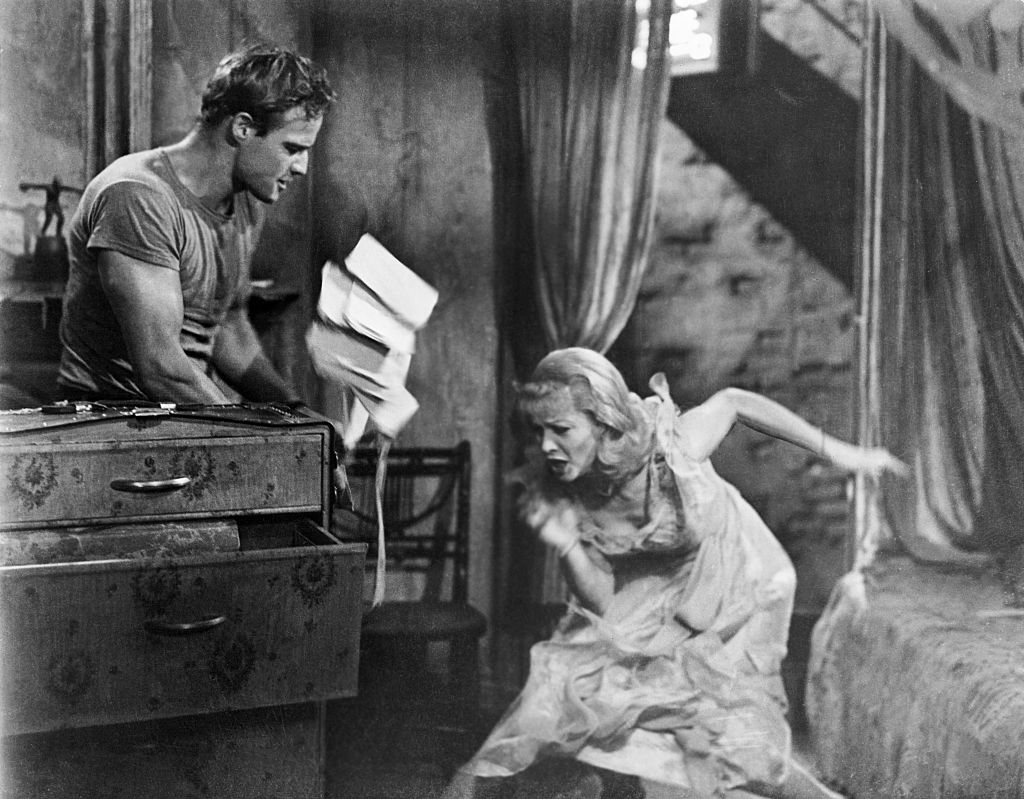

My second experience with Blanche was watching the 1951 Elia Kazan film adaptation of Streetcar. There, she was played by Vivien Leigh—or, at least, I guess she was. All I could see was Marlon Brando as Stanley. That inscrutable voice, those sledgehammer arms, that rock-hard torso. I don't know if any man on screen has ever exuded such raw sexuality before or since. In one of his all-time iconic performances, Brando commands every frame, using his gravity and his physical perfection to ensure both the story and the viewing experience revolves entirely around him. Despite the Hollywood revision to the ending, neither of the women seemed to stand a chance against him. I was obsessed with what he achieved here. Stanley's nasty, abhorrent behavior may have made me want to throw up if I thought about it too intently. But it made me feel.

My third run-in with Blanche was when I saw her played by Marge Simpson in Oh, Streetcar! I thought Marge had moxie, but the unconventional nature of the production definitely interfered with my connection to her performance, and I saw the character mostly as a means for comedy.

The fourth time I saw Blanche was on Saturday night, in the Brooklyn Academy of Music's import of Rebecca Frecknall’s London production of A Streetcar Named Desire. I was there for Stanley—as were, I believe, most of the '90s-born women in attendance—because he was played by soft-boy-turned-gladiator Paul Mescal, a heartthrob whose star power far eclipsed his castmates. But finally, surprisingly, I found myself zeroing in on Blanche, and loving her instead of the abuser who pushes this tragic heroine into the abyss.

Mescal wasn't flattered by the Brando comparison (who would be?), but with a less caricatured performance he was able to make Stanley's moments of uncontrolled anger stab dangerously through the majestic space. Even from far away in a cramped balcony, however, my brain kept telling me "That's Paul Mescal!" every single second I looked at him, at least through the first act. That sort of giddiness is going to hinder the work, but luckily, I did not have the same issue with Patsy Ferran. She was unknown to me going into the show, and so she was only Blanche DuBois—the definitive version.

This Streetcar uses a very minimalist set with only a couple tricks up its sleeve—Springfield's Oh, Streetcar! probably spent more on its production than this did. To use a Stanley Kowalski word, I can't help but feel a little swindled when one of the most expensive shows in the city opts for such a sparse presentation. But what the plain elevated square on stage does do is allow the performances and the script to work for everything. Williams's words are the muscle—authentic, heavy, tirelessly tense in every scene—and Ferran's fresh, bold work gives them a perfect home.

When I'd thought about Blanche before this weekend, I imagined her as a lost girl who'd wandered into a place where she didn't belong. In the Vivien Leigh version, it's almost like Kazan transplanted a character from Gone With the Wind onto his set, and for this reason Blanche's struggle to cope feels natural. Frecknall's Streetcar, on the other hand, is breathlessly energetic—played not with the mournful melancholy of a long hot summer in the South but all the clever zip of a speakeasy at midnight. The lone drummer high above the stage, almost playing God, keeps us on our toes. The dialogue abhors empty space. Early on, Stella describes her husband as special because of "a drive that he has," but the whole play has this ceaseless hunger, this irreverent intensity, that makes you feel its epic drama in your blood.

In this version, you realize that Stanley Kowalski is only really around some of the time. It's Blanche who's the engine throughout, and Ferran brings manic charm to the role that obscures the fact that we all know she's doomed from the outset. Her Blanche remembers that she isn't just a little lost schoolteacher; she's also a woman who's had to learn on instinct how to survive the seediest of Mississippi men. She's well-read and resourceful and can talk and talk and talk, but it's only as she spirals that her words get less coherent or grounded in a recognizable reality. Until then, she holds her own as a flirt and as an older sister. She spars with Mescal on stage, giving a little and taking a little, instead of getting steamrolled by his masculinity. She has just as much power as anyone, until the rest of the characters conspire to take her down.

It was this early Blanche monologue that really emphasized the difference, when she tells Stella how she lost the plantation where they grew up:

I, I, I took the blows in my face and my body! All of those deaths! The long parade to the graveyard! Father, mother! Margaret, that dreadful way! So big with it, it couldn't be put in a coffin! But had to be burned like rubbish! You just came home in time for the funerals, Stella. And funerals are pretty compared to deaths. Funerals are quiet, but deaths—not always. Sometimes their breathing is hoarse, and sometimes it rattles, and sometimes they even cry out to you, "Don't let me go!" Even the old, sometimes, say, "Don't let me go." As if you were able to stop them! But funerals are quiet, with pretty flowers. And, oh, what gorgeous boxes they pack them away in! Unless you were there at the bed when they cried out, "Hold me!" you'd never suspect there was the struggle for breath and bleeding. You didn't dream, but I saw! Saw! Saw! And now you sit there telling me with your eyes that I let the place go! How in hell do you think all that sickness and dying was paid for? Death is expensive, Miss Stella! And old Cousin Jessie's right after Margaret's, hers! Why, the Grim Reaper had put up his tent on our doorstep!… Stella. Belle Reve was his headquarters! Honey—that's how it slipped through my fingers! Which of them left us a fortune? Which of them left a cent of insurance even? Only poor Jessie—one hundred to pay for her coffin. That was all, Stella! And I with my pitiful salary at the school. Yes, accuse me! Sit there and stare at me, thinking I let the place go! I let the place go? Where were you! In bed with your—Polack!

Reading it with the Leigh version of Blanche in my head—a melodramatic, slow, breathy voice—she sounds flighty, meek, untrustworthy, and of course prejudiced. In Ferran's hands, however, this monologue is an absolute jackhammer. It's fast and accusing and filled with the gnarled rage of a woman forced to bury her feelings under a role of polite servitude. For those who weren't in the audience, imagine if the above was spoken with the breakneck frenzy of Barbara Stanwyck ordering around a man on the silver screen. For the first time ever, it got me on Blanche's side, and I never wavered from there. In this Streetcar, it's so much easier to realize that Blanche is both erudite enough to immediately recognize an Elizabeth Barrett Browning line in the wild and shrewd enough to immediately recognize Stanley for the beast he is. In my previous conception, Blanche started low and ended low. Now, I can appreciate the cruelty of her destruction.