Two recently reunited lovers, both of them Palestinian intellectuals, catch up on a rooftop at dusk. Behind them lies the skyline of Jerusalem, a distant but undeniably felt presence. He, a novelist, tells her, a folklorist, about how he spends his days. He still works, but not through writing. “The intifada swept everything away, even my literary ambitions,” he says, unable to focus on a single work when behind every person he envisions “at least four novels, in search of times destroyed.”

Canticle of the Stones (1990) is a film that flows abundantly and unpredictably with many different strands and experiences, but the source is a conundrum: the irrepressible urge to articulate through word and images, directly and through metaphor, the experiences and aspirations of Palestinians in the face of total, aggressive denial. At the same time, there's the feeling that these representations fall short, or can’t fill the representational gaps, when Palestinians, individually and as a people, are constantly facing down the barrel of a gun. This systemic violence, segregation and erasure dictates the grounds on which Palestinians live. Likewise, art by and about Palestinians cannot be fully separated from this system of oppression. Or as the poet Marwan Makhoul put it, in a verse that has been widely shared in recent months during the genocide in Gaza:

In order for me to write poetry that isn't political,

I must listen to the birds

And in order to hear the birds

The warplanes must be silent.

In Canticle of the Stones, writer and director Michel Khleifi addresses this problem of artistic representation not as a theoretical matter, but as an inescapable part of the actual, lived reality of people subject to a militarized apartheid state, through a film that is disparate, expansive, and constantly in conversation with itself.

Its starting point is a Song of Songs for a time of perpetual war. A poetic melodrama where, after 15 years apart, two unnamed intellectuals reunite in Jerusalem in 1989, caught up in the tumult of the first intifada. The reasons for their separation are manifold. He (Makram Khoury) was imprisoned after attempting to prevent the destruction of his family home. Not long after, she (Bushra Karaman) left for America, to attend university and escape the violence and a stifled future, and also the loneliness of her separation from him and the strictures of her conservative family. Their reunion sparks a passionate but uncertain reignition of their affair. The film is a poetic account of the intervening years and the present in intimate, political and mythic terms, and takes place over several days in the hermetic no-man’s-land of a hotel.

As they burrow deeper into their own interior life, traumas and aspirations, and attempt to connect to a larger social and political sphere, the film expands beyond the couple's fictional domain into nonfiction, taking up many different voices. The dramatization of the couple is interpolated, scene to scene and sometimes shot to shot, with bracing documentary scenes of Palestinian life under occupation, depicting events like the Israeli military’s closure of a school and the staff and patients at an overstretched hospital.

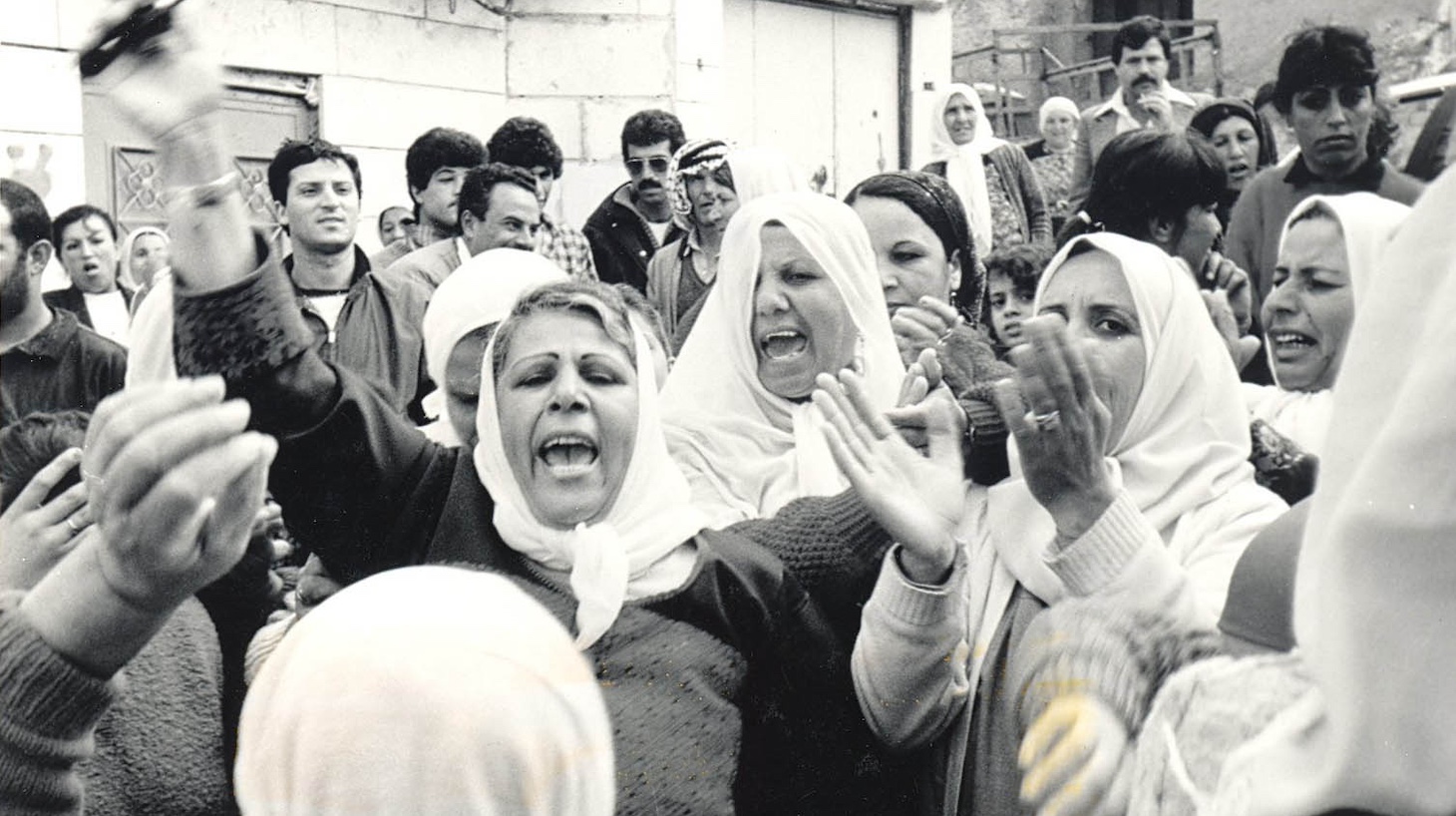

In the film’s back half, following the folklorist who aims to study how "the myth of sacrifice" unfolds through the intifada, it moves into Gaza and the film becomes increasingly dark, despairing and fractured with shots of civil destruction, dead and wounded bodies and their bereaved loved ones. The film’s rhythm here changes, moving in shard-like scenes more organized but not unlike the glut of images of death and destruction flowing out of Gaza today.

Although there are moments where the tale of the two lovers and the world around them, fiction and nonfiction, converge, often these disparate strands chide and chafe against one another, to profound effect. The construction of the film's two separate but coexisting parts contrast dramatically. The scenes of the two lovers are carefully rendered in an impressionistic manner, weaving together different layers of stylization: theatricality, mythicization, historicization, realism. The documentary scenes, in contrast, are defined by their unpredictability, polyphony and immediacy, and the striking repetition of Palestinians looking directly into the camera lens.

The impetus of Canticle of the Stones’ striking mixture of drama and documentary, its insistence on drawing in as many experiences as possible, was born both in the moment, in response to the conditions of the intifada, and from Khleifi’s developing ideas about how to represent the Palestinian experience. Khleifi arrived in Jerusalem in early 1989 with the idea to make a poetic film about children martyred during the intifada. However, overwhelmed by the sheer violence and scale of the situation, he abandoned that idea for a film that would take in as much as possible.

The starting point was still poetic. In the span of a week, he composed a long series of verses that eventually would make up the two lovers’ dialogue. The poem was written in response to a piece by Marguerite Duras, published in the French newspaper Liberation, that praised Ariel Sharon, who at the time was Israel's defense minister. Disturbed, as Duras was a clear and stated influence on his work, Khleifi constructed an answer in the shape of a film that in part can be read as a variation on the Duras-scripted Hiroshima, Mon Amour (1963). Both films are about lovers captivated, scarred and drawn to each other through their personal and collective historical traumas. In the case of the Canticle of the Stones, the bloodthirstiness of the modern, imperial age doesn’t just rage in the past. Instead, it consumes bodies and minds in equal measure, past and present. Alive and unrelenting, battering the edges of Khleifi’s fiction like a hurricane laying siege to a house.

Khleifi has said he conceived of his canticle as an attempt to gain and impart some necessary distance, a wider historical and cultural perspective, to what was happening on the ground. And yet the film is not so distanced that it becomes remote, for his approach to shooting brought a critical, in both senses of the word, immediacy.

The rest of pre-production and production took place in its entirety over a period of four weeks. The filming of the scenes with the two lovers and of daily life during intifada were interspersed. Shooting the documentary scenes often interrupted and reshaped the fictional scenes, and Khleifi and the crew persisted despite the near-constant threat of arrest or even death posed by the IDF. For instance, at one point while the crew was trying to film a martyr’s funeral in Gaza, a soldier put a gun to Khleifi’s head.

This frictional style is reminiscent of the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish, who responded to the intertwined challenge of speaking for himself and for millions of Palestinians by writing poetry that, to quote Edward Said, is “a harassing amalgam of personal and collective memory, each pressing on the other. And the paradox deepens almost unbearably as the privacy of a dream is encroached on and even reproduced by a sinister, threatening dream…”

In an interview with Jadaliyya, Khleifi calls his similar approach a dialectical one, and explains some of the difficulty of articulating certain fundamental questions and fruitful responses about the Palestinian experience, whose multi-layered dimensions have been flattened under extreme pressure and contradictions:

How can I convey the "story" of a people without pictorial memory? What is the intellectual, mental, and temporal path for writing memory in general? Then came other questions that I needed to find answers for in my films about how many accumulated temporalities do we live through simultaneously? How do we deal with a present that becomes instantaneously a past?

These tensions animated Khleifi’s cinema from the beginning. Born in Nazareth in 1951, Khleifi is part of the first wave of Palestinian filmmakers and artists born after the Nakba and raised on those Palestinian lands that now constitute Israel. He grew up with Israeli citizenship and therefore with a greater freedom of movement than most Palestinians. Still, he was firmly a second-class citizen—his childhood was cordoned and steered by strict curfews, military patrols and permits—who belonged to a people whose world has been expressly designed as a panopticon. Khleifi is conscious of and interested in the disparities of the Palestinian experience, as it varies by class, gender, regional, political and other factors, and seeks to articulate them in his art.

For Khleifi, art plays a powerful but ultimately ambiguous role when it comes to liberation. It can expose injustice and power but can’t fully push past it. This comes through in the similar endings of his first two films, Fertile Memory (1980) and Ma’loul Celebrates Its Destruction (1984). Both involve a homecoming where a person displaced in 1948 is brought back to the land they once lived upon and still claim. The scenes could be framed as straightforward statements of revolutionary defiance and positivity, where the dispossessed’s irrepressible sense of justice and humanity takes an imaginative leap over colonialist state power, turning back the clock and taking back the land. However, after the initial frisson, the atmosphere of both scenes becomes one of anguish and confusion. The act of return, once realized, doesn’t feel like victory. The enduring injustice of colonization is reinforced as a problem of the present.

This melancholy differs greatly from the work of Palestinian filmmakers of the generation before Khleifi’s. This earlier generation is epitomized by the Palestine Film Unit, for whom art and armed struggle for liberation were co-constitutive; posters the Unit produced brandished both cameras and weapons held up together. Unit member and scholar Khadijeh Habashneh has recounted how members of the Unit and its sister organization, the PLO’s Photography Department, had fought as fedayeen, and that a cameraperson would often lead the way for soldiers in battle.

This reality is depicted in Scenes of the Occupation from Gaza (1973), a documentary short directed by Mustafa Abu Ali. A dystopian mosaic like the Gaza scenes in Khleifi’s film, the atmosphere of Scenes of the Occupation from Gaza is less despairing, instead expressing a determined fury. A steady pulse of anger runs through the film, surfacing in the quick, recurring cuts to a handgun and a grenade. It climaxes with a young man being questioned by the occupation forces. As the soldier looks to his notepad, the young man gives him a look of indignation, a rebellious flash of anger the soldier doesn’t register, but the camera does. The film responds to the man's look with a match-cut to a final, lingering shot of a grenade, followed by a title card that reads "Long live the Palestinian revolution." This storm of images gives voice to an individual’s, a filmmaker’s and a collective's urge for revolution.

Though Canticle of the Stones is a more ambiguous film, that same look is time and time again directed at the camera. It’s a look of pain but also persistence, a defiant grasp not just for life but for assertiveness and subjectivity, against the odds. It’s given voice near the end of the film when one dispossessed Gazan says that even if Israel were to erase every single Palestinian, the stones would throw themselves.