Who threw the glass in the street, man? That query has echoed in my head ever since I saw D. A. Pennebaker's 1967 documentary Don't Look Back, which captured in cinéma vérité the overwhelming attention that followed Bob Dylan to England in '65, while he was still a solo acoustic act on stage. The documentary crystallizes what is probably the most commonly shared cultural image we have of Dylan: a skinny dude with sunglasses and messy hair and disordered energy, speaking in snide riddles, beset by clueless questions from square reporters.

The glass incident is a representative scene—a bunch of young people, some talented and some not, all on mild drugs, bumbling their way through banal human interactions. Dylan is the de facto host of this hotel gathering, since he's the center of his own universe, and he has to deal with it when some unruly guest makes the dangerous choice to throw glass out the window. He explores the question with confrontational vigor, emanating a "Who the hell are all you people?" frustration within the intense confidence of a famous genius. Making a little cameo here is the Hurdy Gurdy Man himself, Donovan, who kindly offers to help clean up, but Dylan ignores him to argue with some guy who appears too drunk for his own good. Dylan faces up to him with masculine swagger. "Either be groovy or leave, man. You don't have to be groovy for me; just be groovy for anybody who you wanna be groovy for." It's a disorienting mess given meaning by the presence of a camera.

The Pennebaker film provided the template for Cate Blanchett's Oscar-nominated performance in Todd Haynes's obliquely Dylan-inspired film I'm Not There, from 2007, which I once thought precluded the making of a straight biopic like A Complete Unknown. A man who tried so hard to be an enigma wouldn't allow himself to be explained in such a formulaic, linear way.

I have yet to see Timothée Chalamet's portrayal, which has been in theaters for a week. I'm not excited. 1961–65 is already the most picked-over and depleted chapter of Dylan's mythos. If I were making a movie, I would have started with the glass—with the sheer absurdity of being surrounded by unpredictable strangers and the pressure to be Bob Dylan for all of them. From there, I'd follow Dylan through the motorcycle crash, his retreat from the spotlight, his active attempts at career sabotage, his first marriage, and I would peak it with a much more interesting live performance than the Newport Folk Festival in 1965: the 1974 "comeback" stadium tour with The Band, where he screamed all his old hits in altered form for a crowd that badly wished it had been at Newport instead. That's the moment, to me, when Dylan the iconic entertainer and Dylan the mysterious musician reach a fragile truce. It can't be a coincidence that the album that followed, Blood on the Tracks, is the landmark that critics still use to judge him in the present day.

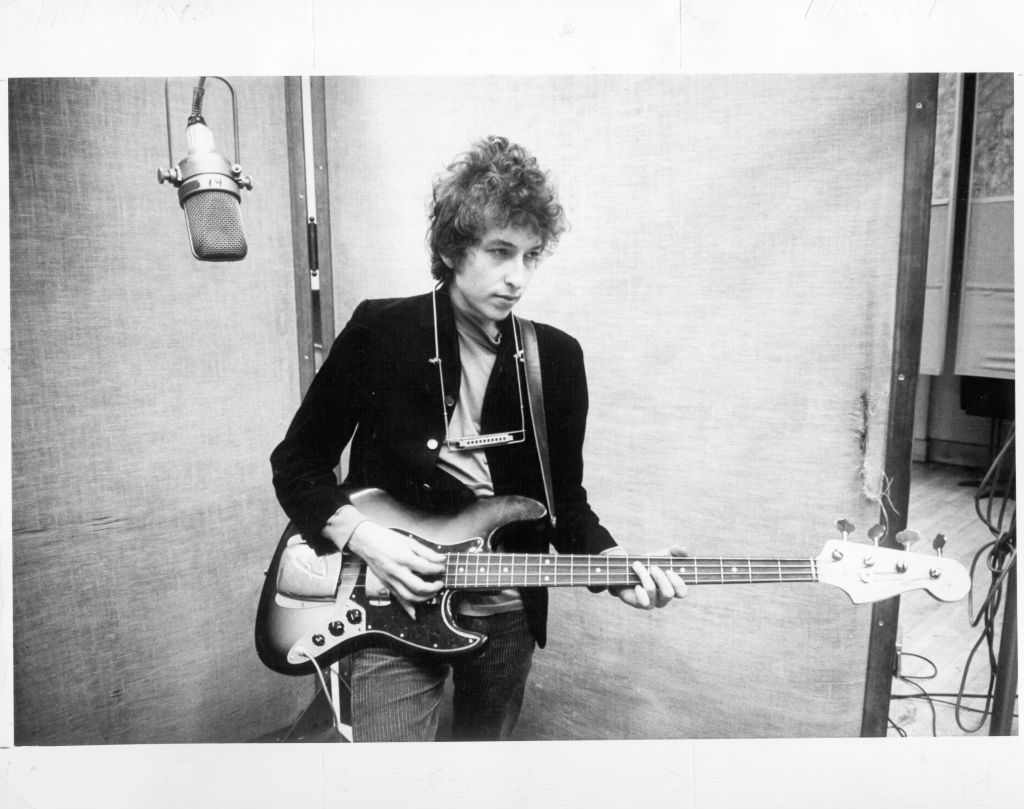

I think about Bob Dylan often. Not as much as I did when I was, like, 20. But still. I had my mind blown by a car radio playing "Like a Rolling Stone" when I was a kid. I got a budget greatest-hits collection. I followed that into maybe a halfway complete set of albums. And then I became the kind of person who goes even deeper. I read Chronicles and explored the bootlegs and deep cuts and covers, looking for value in his Christian phase and forming opinions on Daniel Lanois's production. I saw him live once, in 2013, one of those trademark shows where the crowd is mostly paying homage to something that once was, and fans struggle to admit to themselves that they don't actually recognize the songs that he's playing. I used to have this big poster of him in the studio in the mid-'60s that I carried around from bedroom to bedroom when I lived in Ann Arbor, in this sort of overwrought homage to something I once heard about Van Morrison keeping a picture of Lead Belly.

I still listen to Dylan a lot, and I like to talk about him even more. His music and lyrics lend themselves to endless discovery. He's so prolific that it's a genuine challenge to listen to everything—a treasure hunt to find the best of what he did outside the core canon. But what I stopped doing, once I got old enough, is worshiping him.

Something Dylan's always been amazing at is acting like he knows everything. This is bolstered by the fact that he's probably written dozens of transcendental lines, but it's also a big part of his offstage charisma. Whether he's the unreadable old man of today or the amped-up chatterbox of the '60s, he's always given the impression that he knows a secret and you can't have it. I fell for this bit hard when I was a kid, both with Dylan and with Neal Cassady, the freewheeling all-American id that Jack Kerouac immortalized in On the Road. They had momentum. They went after what they wanted. They could go to New York. I yearned for that freedom.

Last month I read Kerouac's Visions of Cody, about him and Cassady, revisiting that pair for the first time since I was a teenager. I found it a little annoying and exhausting, the way Kerouac rambles weightlessly, like a coin flipping in midair that never actually comes down on either side. I realized what I had actually envied most, back then when I read about them for the first time, was that they had means of transportation, and therefore a means of escape.

I don't roll my eyes anywhere near so hard at Dylan, whose body of work I still venerate. But it was funny, at age 29, returning to Don't Look Back and seeing for the first time how young he is, and knowing how much anyone at that age still has left to learn. With the added experience of having gone to parties in my early 20s, I could perhaps understand him now as a guy who was fighting to keep it together, who was just saying words and waiting to see what stuck, who badly wants to be cool, who's still figuring out what kind of drugs he likes in his system, who's not entirely sure about the relationship between actions and consequence. Nobody can or should be like that forever, but it's kind of a fun place to be, still testing the guardrails of adulthood while feeling the freedom that comes with decades of possibility ahead of you.

If I end up seeing A Complete Unknown, it'll probably just be to look at Chalamet's often-imitated, never-duplicated beauty on a big screen. I cannot imagine that there's anything more to that mainstream version of Dylan that hasn't already been covered. But I think I'll find meaning in his work forever, and not just because I want to know who threw the glass in the street. Dylan's 83 years old now. That's a whole life for me to catch up to, tied to album after album of wild turns and sober reflections. It's still four more years until I get to Blood on the Tracks.