Defector has partnered with Baseball Prospectus to bring you a taste of their work. They write good shit that we think you’ll like. If you do like it, we encourage you to check out their site and subscribe.

This story was originally published at Baseball Prospectus on October 23.

Clayton Kershaw is terrible in the postseason, unless he isn’t. Every year he seems to cruise through opposing lineups, until he doesn’t, and then the postseason choker narrative only gets stronger. Perpetually brilliant in the regular season, Kershaw always manages to find a couple extra runs to tack on his ERA in October.

But behind every Kershaw performance there is a managerial decision lurking: Dave Roberts decides to keep him in, usually just long enough to get him in serious trouble. Roberts has long been criticized for not pulling his ace earlier, which is an inevitable judgment with the hindsight we have and the runs we’ve seen roll in against him. A bit of statistical analysis shows that Roberts has probably been making the wrong decision with Kershaw on the mound even without the benefit of hindsight. A careful look at his performances might show that Kershaw ought to have been removed a little sooner nearly every time.

It’s often deeply unfair to criticize managerial decisions. Sure, some are head-slappingly obvious brain farts even in the moment, but it’s easy to forget that managers have to make the calls under immense pressure, with a time limit, and without knowing how any of the following plays will turn out. A lot of the criticism of Roberts has come from the retrospective position of knowing that Kershaw would give up runs. It takes a lot more courage to pull your ace in the moment.

The problem with a retrospective analysis, no matter how sober and reflective, is hindsight bias, the pernicious human tendency to justify a choice based on what happened afterwards. Because we know what fate was awaiting Kershaw—often, he was lit up—we’ll be tempted to say that he should have been pulled earlier. With the benefit of hindsight, he should have! But it’s not fair to Roberts, who didn’t know what would happen at the time, to judge him on a retrospective standard.

Instead, we need an objective way to judge Roberts’ performance based on the information available to him at the time. Of course, it’s impossible to get inside his head, but thanks to Statcast, we do know a little something about Kershaw’s fatigue level, based on the speed and break of his pitches. As it declines, so too does his performance, and once it crosses a critical threshold, the Dodgers would be better off with one of their (usually) excellent relievers, rather than a winded and diminished ace.

In order to avoid the trap of hindsight bias, I built a Random Forest model to predict Kershaw’s value on a pitch to pitch level, using the speed and break of his pitches, the pitch type he was throwing, and most importantly, his pitch count. I trained the model so it only knew about Kershaw’s regular season outings from 2017-2019; it was completely blind to what had befallen him in October.

The model takes Kershaw’s performance data on each pitch and spits out an estimate of how valuable he will be (in runs) on the next pitch. There’s a lot of noise from throw to throw, but if his predicted value starts to slip over a 5- or 10-pitch run, that’s a good indication that it might be time to pull him from the game.

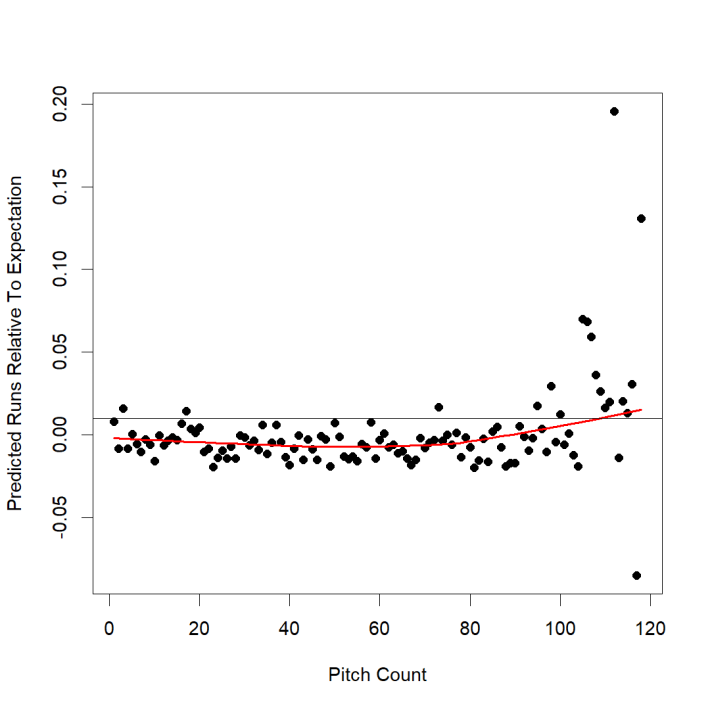

In the regular season, the model tends to forecast Kershaw’s performance (the red line in the chart below) starting to fall below a reliever only around the 100th to 110th pitch. (The black line represents the expected run value of a reliever on the same scale.) That’s about how long Roberts (or any modern manager) tends to leave their pitcher in, on a good day. After that point, his performance (like most starters) starts to explode in terms of run expectancy (not to mention, his injury risk probably starts to increase as well).

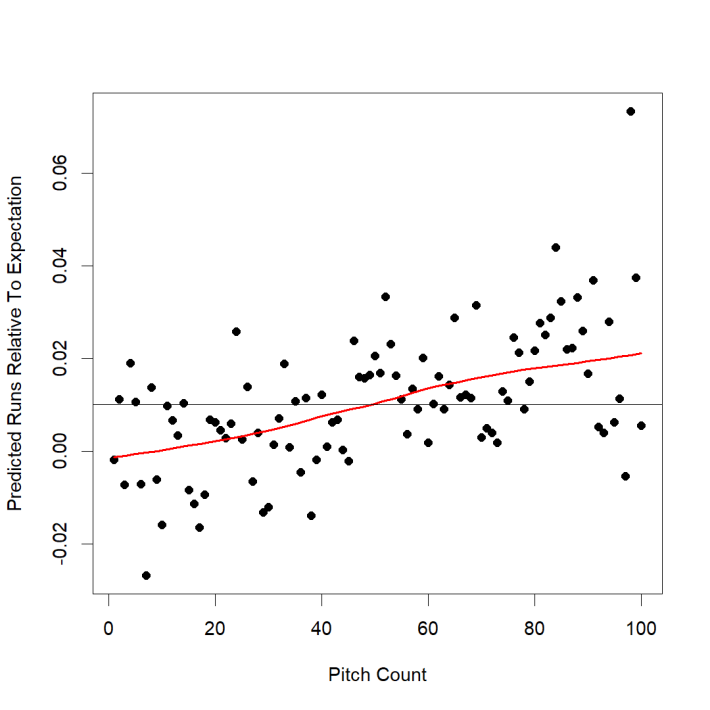

I took the same model and had it predict Kershaw’s expected runs performance in the postseason by pitch count. Here, it had a very different take on when the ace ought to be pulled.

The red line, representing a smoothed estimate of Kershaw’s performance, crosses the black line, representing the reliever who is available to replace him, at pitch number 50 instead of pitch number 110. Roberts does tend to pull his ace early in the postseason, but only by about six pitches. His average pitch count rises to about 94 pitches, according to Devan Fink, long, long after the model thinks his performance would be bested by the relief staff.

This gives some credence to the idea that Roberts is keeping the Dodgers legend in too long. But the model doesn’t tell us why it thinks Kershaw should be pulled early in the postseason. For that, we have to go to his performance indicators.

The most obvious flag that a pitcher is fatigued is when his fastball velocity goes down. By that standard, there’s nothing that suggests Kershaw has a problem in the postseason. He tends to throw significantly harder in October than in the regular season, and on top of that his velocity doesn’t drop as quickly over the course of his pitch count. In regards to pitch speed, at least, there’s no sign that Kershaw has a playoff problem.

However, there is a tell-tale sign that Kershaw’s performance is degrading, one that Roberts seems to have missed. Starters tend to throw their fastballs more early on, blowing by hitters, before going more to their secondary stuff later in the game to earn tougher outs. Kershaw is no exception to this pattern: Early on, he throws about 50 percent fourseamers, which declines over the course of his pitch count to about 33 percent by the end of the game.

He goes through the same progression in his postseason starts, only he does it much faster. In the playoffs, it takes him about 30 fewer pitches to show the same decay from one-half fastballs to one-third fastballs. There’s a crucial point the model seems to use to determine when his performance is failing, and that’s when he’s down below about 40 percent fourseamers. At that point, in most Kershaw starts, the model starts to forecast bad performance, and he often hits that level much earlier in the postseason—as soon as 50 or 60 pitches in some starts.

There are some very important considerations that this model cannot handle right now. The most important is reliever availability. Right now, the model assumes that a league-average reliever is always there to cover any innings the starter can’t. But that’s not how rosters work: Managers don’t have an infinite supply of perfectly average relievers available to them for the rest of the game. Rather, they have a finite supply of very particular bullpen arms, each with their own strengths and weaknesses, recent performance and possible injuries, and limited endurance. As a result, the model can sometimes suggest a manager ought to pull a starter implausibly early in a game, though this does not appear to be the case in Kershaw’s regular season starts.

Along the same lines, the model can’t ask Kershaw how he’s feeling the way Roberts can. All it has is the performance data to go on, although it’s possible that in some cases that’s a better guide than a pitcher’s self-report. In this case, Kershaw is indicating his fatigue in the way he goes to his secondary pitches earlier. For whatever reason, when he feels like he needs to call on his slider and curve more, that seems to be an excellent signal that he’s reaching the end of his rope.

Even though this analysis calls Roberts’ decision making into question, it doesn’t exactly vindicate Kershaw either. Perhaps he’s simply exhausted over months of regular season throwing, but the venerable lefty really doesn’t seem to have the same stamina in October. It’s on Roberts to make the call to pull him—and if he had, Kershaw’s ERA might not have ballooned so much—but it’s also on the ace to keep a little bit of his best stuff for the most crucial moments. In the end, his postseason choker narrative may be as much a product of the lingering fatigue of a long season as it is Roberts’ too-slow hook.