People have been quoting The Simpsons to me so often, and for so long, that even if I don’t recognize the quote, I am able to recognize that it's from The Simpsons. When I do recognize the quote, it’s not because I've seen that episode, but that so many people have quoted it before. People quote The Simpsons like it’s a secret handshake with the whole world—and at this point, it basically is.

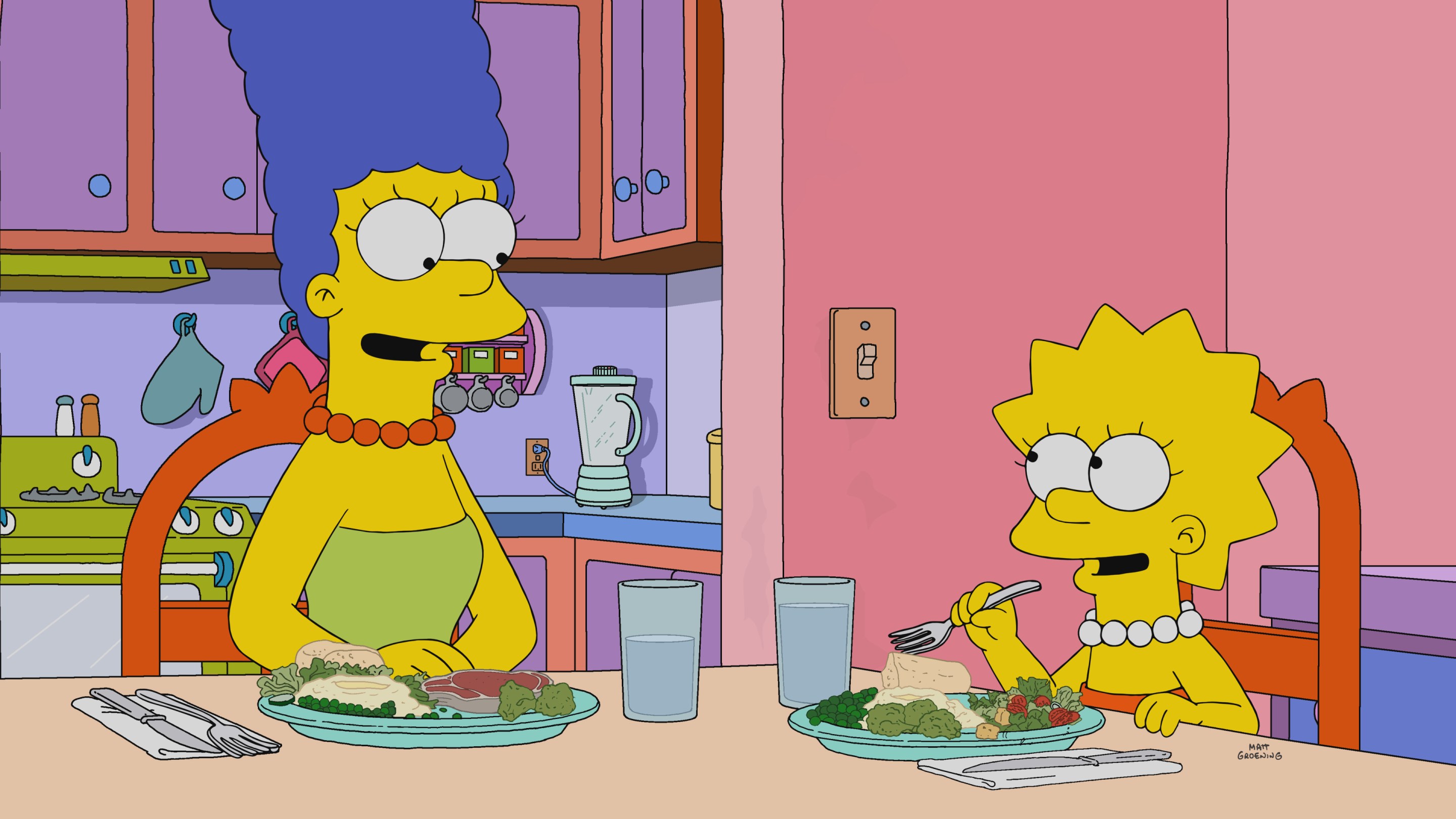

The Simpsons is going into its 37th season. Thirty-seventh. It's so embedded in the culture that someone like me, who never really watched it, still can’t escape its influence. The remarkable thing about people quoting The Simpsons is that they still do it like it’s niche. It remains a mark of a particular sort of taste in a way that quoting any other highly successful network television show could never be. The Simpsons is an institution. Who quotes institutions?

Stupid TV, Be More Funny: How the Golden Era of the Simpsons Changed Television—and America—Forever is a long title for a reasonably concise answer to this question. It’s kind of an oral history, but kind of not at the same time, because this book has a clear anchor: writer Alan Siegel. By his own admission, the Ringer staff writer and now author (his book came out in June and is available here) has spent much of his professional life trying to figure out why The Simpsons had such a hold on his generation. He's a middle-aged white guy, which means when The Simpsons hit television in 1989, he was exactly the right age to receive it in a formative way. And he’s the perfect guy to write this book, because The Simpsons, regardless of how huge it got, was conceived by and for guys like him. To get at the essence of its staying power is to be attuned to that core from the inside—and to be self-aware enough to interrogate it. As Siegel acknowledges, The Simpsons was deemed "subversive, progressive and ground-breaking," but it was all of those things within the limits of a group of straight white guys, specifically "super smart, super funny, super nerdy" straight white guys. With The Simpsons, Siegel writes, "the nerds were cool," before the cool nerds would come to define pop culture.

So how did the outsiders get inside Fox? They had some insiders who trusted them. The origin story circulating around the time it premiered was: Edgy indie cartoonist makes it big. It’s true that without Matt Groening, The Simpsons would not exist, but without co-developers Sam Simon and James L. Brooks, The Simpsons wouldn't come to dominate the culture in the way it has. Brooks was, at the time, the very respected co-creator behind successful sitcoms like The Mary Tyler Moore Show and Taxi (not to mention Broadcast News, a perfect movie). It's hard to imagine, but this was the era in which a studio as big as Fox—struggling for a hit at the time, but still—could just want to make a guy like Brooks happy. That meant Brooks could ask for what he wanted, and what he wanted was what any artist in Hollywood wants: zero executive interference. "That meant no notes on scripts," Siegel writes. While that kind of demand would be unheard of now, it was rare back then, too. But it sounds like it was staunchly honored for Brooks’s sake. "We truly never saw Fox executives," writer Jeff Martin says in the book. "We didn't know what they looked like.”

The Simpsons was designed to appeal not to media executives but to Harvard Lampoon grads, because that's who Simon—with whom Brooks had worked previously—wanted to appeal to. Siegel calls the magazine "a finishing school for comedy nerds," and writer Jon Vitti tells him of Simon (who died in 2015), "It was important to him to make The Simpsons feel different than other half-hour shows, to have conceptual comedy elements like SNL and Letterman did.” So Simon hired young guys like Conan O'Brien to work alongside older veteran late-night comedy geniuses like John Swartzwelder. The latter would become the most prolific writer on the Simpsons staff—responsible for many of the old-timey references and for flawless scripts that served as a model for everyone else. ("To alcohol, the cause and solution to all of life’s problems!” is a Swartzwelder line.)

Animated shows like The Simpsons usually came out of storyboards, not writers’ rooms, but this one was run like a sitcom with the directive from Simon that "every Simpsons episode should be like no other Simpsons episode we've ever done." Not only were the writers free of notes, they were free to play. They played with structure, with chronology, and packed the episodes with layers of jokes. Then the show hired a cheap animation studio (Klasky-Csupo) and actually listened when they said Groening’s black-and-white drawings would not fly on television. That’s why The Simpsons literally became multi-colored.

But the show also had some reins on it to keep it from going off the edge entirely. That was Brooks, whose mission was to keep it grounded in reality—as well as in the family—which meant if you fell off a cliff in this cartoon, you died. Siegel writes that Simon gave the show its brain, Brooks its heart. Throughout his book, he repeats the uplifting mantra that held it all together, keeping The Simpsons ultimately buoyant: In the words of writer George Meyer, life is "absurd, and punishing, and undignified. But it might be worth living."

When the show premiered on Dec. 17, 1989, as a Christmas special, The Simpsons writers expected a cult following—it became a cultural behemoth instead. “We thought America was responding to our really smart jokes," writer Jay Kogen tells Siegel, "and then Fox gave us research that said that the audience likes the pretty colors, and they like it when Homer hits his head." From the start, Groening had said, "a perfect Bart Simpson action is really smart and really stupid at the same time." The show’s ability to do two things at once—to work for both kids and adults, but also to work inside the system while commenting on it at the same time—meant a wider audience. People who liked Dan Castellaneta’s take on the script’s "annoyed grunt" ("D'oh!") could quote that alongside the people who ate up the show’s “cromulent” vernacular. Still, no one had set out to make catchphrases. Simon was clear that Bart’s lines that took off—“Eat my shorts!” “Don’t have a cow, man!” "¡Ay, caramba!"—were all derivative because kids are derivative. And the references to pop culture, like an entire episode satirizing Scorsese’s 1991 thriller Cape Fear, appealed to Siegel’s generation in a similar way.

"Some felt like inside jokes. And that's a big reason why Gen Xers and elder Millennials loved the show when we were growing up. We inhaled TV, music, and movies," Siegel writes. "Inadvertently, we invented modern nerd culture. It became our shared language." He also writes about the online newsgroup alt.tv.simpsons, a proto-fan site, where—in a tone that is now incredibly familiar —"mixed in with valid criticism and good-humored insight was a sense of entitlement." This is how you get people treating The Simpsons like an inside joke as it sells out merchandise in the malls of heartland America.

While people still quote The Simpsons, it’s rare that those quotes come from more recent seasons. The show’s golden age is considered around Season 2 to 10, which means the last time it was considered really good was in 1999. Swartztwelder thought they peaked earlier than that. “I’ve always thought Season 3 was our best individual season," he told The New Yorker in 2021. "We had learned how to grind out first-class Simpsons episodes with surprising regularity, we had developed a big cast of characters to work with, we hadn’t even come close to running out of storylines and the staff hadn’t been worn down by overwork yet."

In that time, the showrunners changed—David Mirkin, a live-action director, was particularly good at producing indelible images like Homer in the hedge—writers rotated out, they started hiring more women. Siegel devotes a few pages to women being sidelined in the early seasons of the show, resulting in the female characters being less developed. As producer Larina Adamson puts it, of the Simpsons team: "They came from backgrounds, you know, where I don't think a lot of 'em had a lot of female interaction." To avoid stagnating, the show stayed nimble, which meant it ventured outside reality more, but that also meant it lost its footing. As Siegel writes, "Homer got painfully dumb, the story lines got zanier, the jokes got broader, and celebrity guest stars multiplied."

That The Simpsons’ golden age still carries a bit of swagger is a function of social media being a larger version of its early online community, in part because there’s nothing else like it—the industry no longer makes room for creative work like this. Everything is run by executives and their notes now. And the power that businessmen have accumulated over the past two decades has come at the expense of the artists. The kind of protected freedom the Simpsons creators got‚ not to mention those elaborate lunches that added up to $300,000 a year—the trust which produced so much experimentation has been replaced by an assembly line of sure things.

“It’s kind of the Silicon Valley shift of focusing more on the business, making sure that the business doesn’t get lost in the creative,” Sony Pictures TV president Jeff Frost said in 2021, of how the landscape had changed. Instead it’s become the other way around: The creative is now lost, or at least often really hard to find. There's a reason Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg’s latest show, The Studio, revolves around Hollywood executives and even includes an episode called "The Note." Goldberg, who wrote for The Simpsons in 2009, has said The Studio came out of their early years in the industry, right after The Simpsons stopped being great. “When we were young writers in need of a job, we were in a notes session with an executive,” he told Emmy Magazine. “In the middle of the meeting, the exec put his head in his hands in defeat and said, ‘I got into this because I love movies — but now I have this fear that my job is to ruin them.’”

Because Swartzwelder always had the best lines, I’ll end with this quote he gave The New Yorker about the halcyon days, when executives like this could be banned from the room: “All we had to do was please ourselves. This is a very dangerous way to run a television show, leaving the artists in charge of the art, but it worked out all right in the end. It rained money on the Fox lot for 30 years. There’s a lesson in there somewhere.”