OAKLAND, Calif. — Right after Domingo Germán pitched his perfect game last Wednesday, the scrum assembled in the Coliseum’s press lounge. There was the TV camera pointed at a backdrop emblazoned with a New York Yankees logo. That was where Germán, Aaron Boone, and catcher Kyle Higashioka would deliver the expected platitudes about the historic night.

Unexpectedly, I was also there, standing around and waiting while my phone blew up. Some were the text messages you’d expect after a night of sports history, some form of “that was awesome you got to be there for that!” And then there was the other kind. That one was some variation upon “I’m so sorry you had to experience that.”

“Do you even have thoughts other than *screaming* rn,” one of my friends texted me.

“No” was the only reply I could muster.

I was at the Coliseum to work on a story and had gotten all of my interviews done pre-game, but I always stick around to watch the game; as a baseball writer who loves the game, why would I leave? I figured I would watch some baseball, on my first regular-season big league credential after 11 seasons in the minors. Maybe I would find some more stories that way, too. Or maybe not, but I figured it would at least be an enjoyable night at the ballpark.

What I got was something much more complicated than that. It was, for starters, just the 24th perfect game in MLB history; it was thrown by Germán, who was suspended 81 games at the beginning of 2020 for violating the league’s domestic violence policy. As The Athletic would later report, citing anonymous league sources, Germán had slapped his girlfriend at a gala and later became so physically violent that she hid from him and reached out for help.

Earlier in the week, I’d found that a person who had sexually harassed me was getting more professional recognition. At the time, that made it hard to focus; how could someone who caused so much hurt be recognized as if it never happened. I’ve also survived intimate-partner violence and lived with that trauma, which shrunk to the size of a footnote in my abuser’s success. And then there I was, watching Germán’s perfect game. It was a familiar feeling; in the shadow of that historic success, it was as if everything Germán had done never happened.

This wasn’t ever the way I wanted to write about witnessing a perfect game.

About the fourth inning, I realized Germán was perfect. I didn’t think much of it, as someone who made an offhand tweet two weeks ago saying I would never see a no-hitter. And then it kept going. In the sixth, he struck out two more A’s batters, swinging. In the perfect seventh, another strikeout. All the while, tweets flooded my timeline about Germán’s past abuse, reminding me of all the abuse I've survived. I kept watching. I had a job to do.

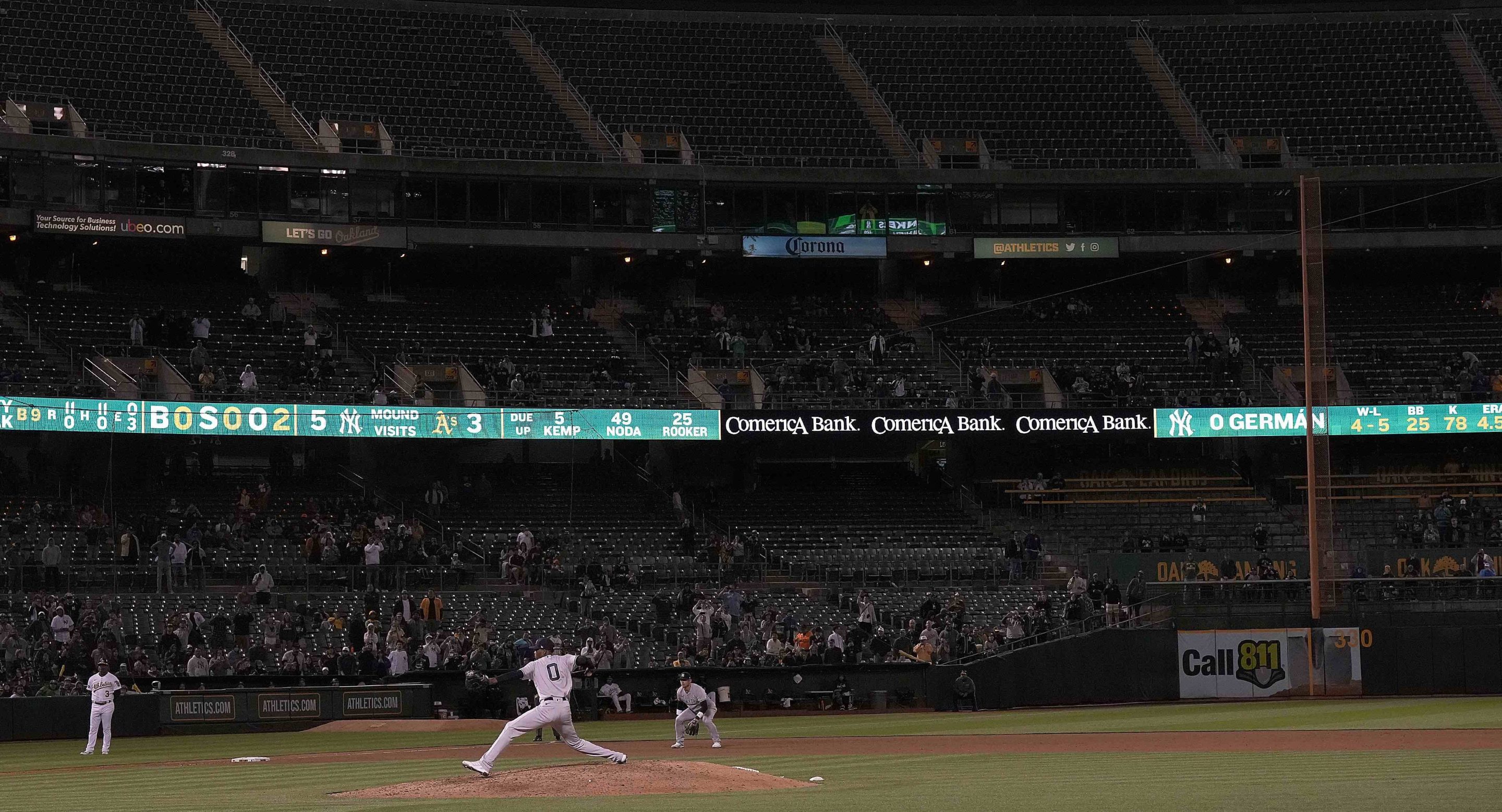

It did not get easier. Around the eighth inning, I texted a friend: “I AM GOING TO THROW MY PHONE OFF THE VALUE DECK.” I’d said the same thing to that friend a decade ago, also while at the Coliseum, when my abuser wouldn’t stop contacting me. The press box wasn’t a place for me to have a trauma response, but a friend’s inbox certainly was. Later, when the perfect game became official, I stared blankly at the field. A crowd of mostly Yankees fans chanted phrases like “PERFECT GAME.” I texted my friends, “I cannot believe I am so displeased at seeing a perfect game.”

When you’re in a scrum, you don’t know what the person next to you has been through. You probably don’t know much about them at all, beyond their name and outlet. That night at the Coliseum, I was one of them—a name with an outlet attached, another human body in the scrum, trying to compartmentalize everything because I was still a journalist, and there to do my job.

And then, suddenly, I was standing next to Germán and interpreter Marlon Abreu as they were being asked questions such as Is Oakland your second-favorite city now? All the while, I thought about my harasser and the recognition he was receiving. Witnessing Germán throw a perfect game felt familiar, but on a larger scale. The feeling overwhelmed me. I couldn’t speak when he was available for questions.

Germán’s suspension was brought up only once, to Boone, by a reporter asking how much Boone had seen Germán grow since then. “A ton,” Boone answered. “Those of you who know him or are around him ... He’s such a sweet guy. He’s definitely been through a lot and taken ownership of a lot. It’s important to him to be a good teammate and a good guy, and he works hard to do that.”

Again, these were the expected platitudes, but this sort of non-answer to a not-quite-question still cried out for a follow-up. But how? How do you ask a follow-up question about precisely how Germán has taken ownership? What does “a lot” actually mean when it’s clear those speaking only want to focus on the perfect game? Were Boone’s circular compliments about growth supposed to be enough? The scrum moved on to other questions, but I couldn’t. I thought about pressing, but couldn’t bring myself to. Nobody told me not to ask, but nobody really had to. I could feel it in the room. Nothing felt like a “right” time to press further.

Nothing felt right overall. I spent an hour in the press lounge after the game, waiting for each interview but frozen with the sinking feeling of having just watched what should be an incredible feat marred by the actions of who completed it. When Higashioka said it was a “privilege” it was for him to be behind the plate catching that night, all I could think about was how what felt like a privilege for him could cause so much pain for so many others.

I know I was not the only baseball fan who felt so horrible that night. There are other survivors of harassment and abuse who also love the game of baseball, and they also watched a man who once got so physically violent that his girlfriend had to hide from him get lauded as if all that never happened. Perhaps some of them were in the press room with me, and similarly unsure how to move.

Germán apologized publicly in 2021. MLB said, along with the 81-game suspension, that he would do counseling and make a donation to a nonprofit that works with victims of domestic violence. I have no way of knowing if his apology was genuine, or if he changed his behavior afterward. Maybe he did. Maybe he didn’t. I only know that for myself, as a survivor of sexual harassment and an abusive situation, watching his perfect game felt like a reminder of my own experiences, and watching as that performance washed away that stain after the fact felt exhausting, and familiar. I was never afforded a personal apology from my harasser or my abuser, something I know I will never get, nor do I seek.

What should’ve been a milestone moment ended with me, hours later, finally able to let my guard down and scream into the night in the Coliseum Complex parking lot. For me, it will always be the worst perfect game in MLB history.