Defector has partnered with Baseball Prospectus to bring you a taste of their work. They write good shit that we think you’ll like. If you do like it, we encourage you to check out their site and subscribe.

This story was originally published at Baseball Prospectus on November 22.

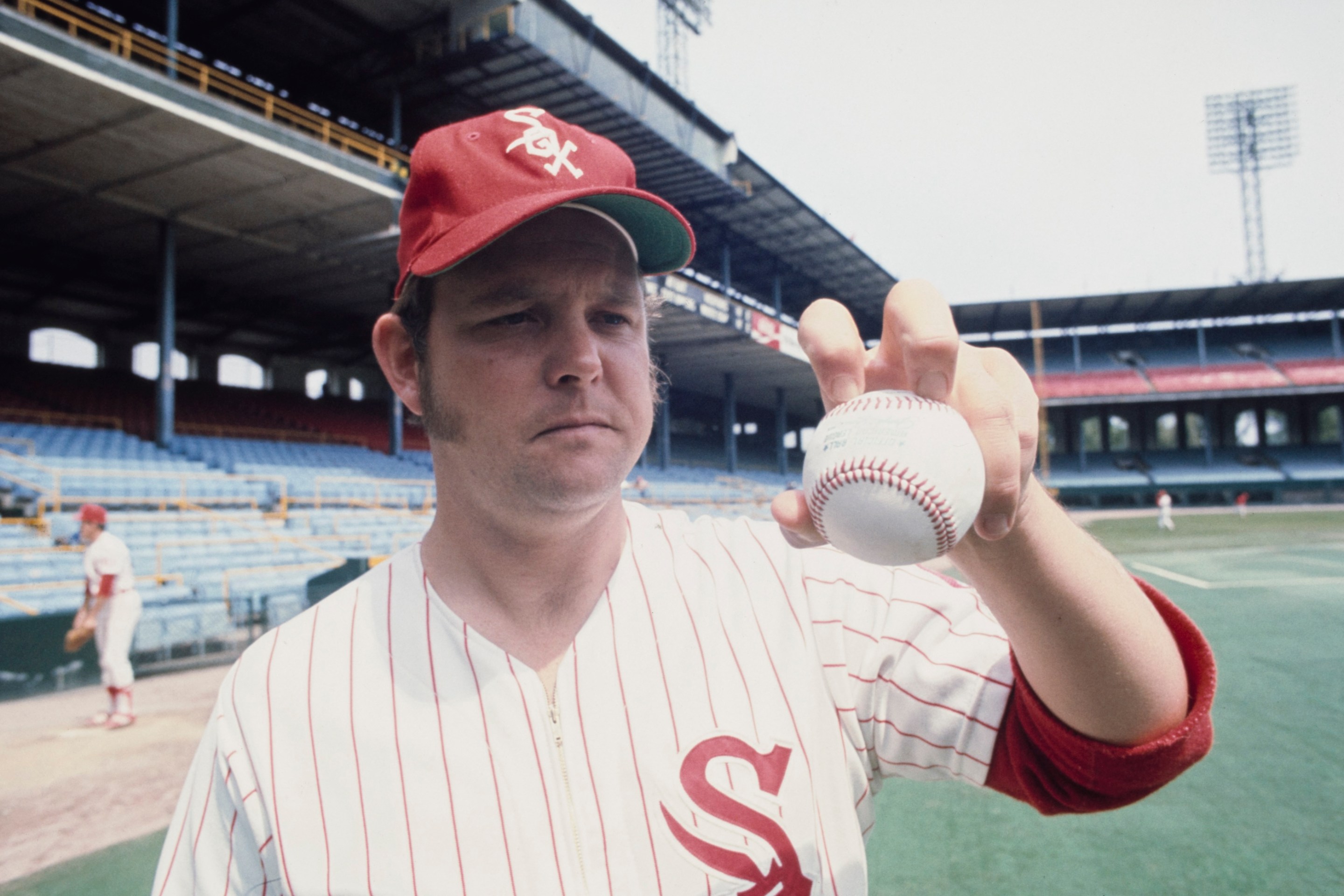

It is springtime, 1972; you can tell because there are men in the background, wearing high-waisted red slacks. Wilbur Wood is frozen in action, despite containing the least potential energy of any man ever. The intended iconography is of the pitcher, post-release, glove raised, ready to field his position. Instead his left arm, encased in a wrinkled warmup jacket layered beneath his uniform, dangles limply from the shoulder. His cheeks are puffy, but whether from tobacco or the previous evening’s debauchery, it’s impossible to tell. His eyes are both tired and bored at the same time, a level of sun-creased weariness only possible in an older generation of ballplayer, the kind who spent their childhood scrubbing foundry ladles, smoking entire packs of cigarettes daily, or both. This is not a man who is playing a kid’s game. This is a man who is working, and would prefer to be off work.

Wood both played and pitched like he stepped out of the 19th century. A bonus baby thrust into the majors as a teenager he could never establish himself with his hometown Red Sox, nor later with the Pirates. It wasn’t until a trade to the White Sox, and its elder statesman and fireman Hoyt Wilhelm, that Wilbur Wood became Wilbur Wood. The young man had practiced the knuckleball for years, and Wilhelm sat him down and helped him with some of its finer points: an over-the-top motion, to give the pitch more drop, and to lock the wrist into a snap-push follow through that prevented any twist that might give the ball spin. For two years Wood teamed with Wilhelm to provide the slowest, and one of the most effective, relief tandems in baseball. When the Hall of Famer moved on, Wood took over as fireman, saving 52 games between 1968 and 1970.

The knuckleball has always carried with it not just a mystique, but a sense of fraternity. Unlike triple-digit cutters and frisbee sweepers, the products of genetic jackpots and endless training, the knuckler feels like something anyone should be able to do. And as it becomes obvious that it is not something anyone can do, that inclusivity is replaced by an invisible exclusivity: That these men gifted with this talent are different, but in a way that can’t be characterized, or predicted.

We’ve come to accept the death of the knuckleball, its spirit, without really understanding why it’s dying. It’s a sense of upward mobility lost, the fading idea that we too might have something hidden inside us, on the edge of our fingertips. Our celebrities and our athletes are no longer the children of tradesmen, but millionaires. The amount of time and money it takes to be special is so great that it’s too late for many of us, and even our children; one must peer ahead generations to see opportunity.

Even in Wood’s time, it was often too late. In 2019, Mark Liptak interviewed Wood, who explained what he said to so many pitchers who approached him in their own times of trouble:

See, if you are trying to learn the pitch because you’ve had an injury, it’s too late. I used to get a lot of calls when I was playing from pitchers who got hurt, and they’d ask about throwing it. The knuckleball isn’t something that’s learned overnight. I threw it for years, from when I was in high school. It takes that long to get used to it. What major league organization is going to give a pitcher three or four years to master the pitch?

The knuckleball isn’t a tinkerer’s pitch. As Wilhelm told Wood in 1966, as the younger pitcher struggled to gain confidence with it, you either throw it all the time or not at all. You had to specialize, but that specialization wasn’t like the kind that marks modern training. It isn’t pushing for a fraction more, an extra wrinkle. You have to cut yourself off from all other futures, long before you can ever know what they hold, and settle on this one. Today a 25-year-old can barely be expected to settle on a profession.

This is why the knuckleball is so romantic: It’s always seen as a last resort, the chips all pushed in, ignoring the fact that the truly successful knucklers had this escape plan mapped out well in advance. For Wood, after five failed major-league seasons, it was the only choice, and the right choice. He was, in those invisible italics, a knuckleballer. But even among those he was special. He threw his slower than the Niekros and Hough and even the quadragenarian Wilhelm. He threw it for strikes; his 2.4 walks per nine innings was the best rate of any modern practitioner of the butterfly. He needed fewer pitches, and could throw more. And he had, locked in that same code, a particular resilience that made him not just great, but alone.

Occasionally a player will break baseball. They’ll display some talent, produce numbers that cannot be, like a solar eclipse or a rain of frogs. They disorient, discomfit. Occasionally these outbursts are simple, and direct, like the record-setting home run race of 1998, or Ohtani’s destruction of the unreachable 50/50 season. Sometimes it’s more subtle: Four times, a pitcher has posted an above-average ERA beyond the age of 45; Wilhelm posted three of those efforts, and Satchel Paige the fourth. Wood’s superpower was even more imperceptible than that. In 1971, a spring injury (and Wood’s holdout, which prevented him being traded) got him relocated into the starting lineup. Wood said he preferred relief; he liked showing up believing he could pitch in every game. He did his best to accomplish that as a starter, as well.

Over the next five seasons, he averaged 45 starts and 336 innings a year. He won 106 games—only 12 active starters have more than that number in their careers—and threw more innings than Jacob deGrom has in his 11 major-league seasons. He accumulated more rWAR (39.1) than Fernando Valenzuela, Jake Peavy, or Catfish Hunter in their lifetimes. Just by being there, and throwing strike after strike, every fourth day, and sometimes every third if the situation called for it.

They’re ridiculous numbers, deadball-era numbers, so much so that it’s easy to ignore them as some sort of anachronism, teleported into modern day. There is no film of him pitching online, and if there were it would have been destroyed. He does not fit baseball. He was the last pitcher to throw 345 innings in a season, to start 45 games, to start both games of a doubleheader. He was the last of his kind, in the sense that he was the only one of his kind.

If he had enjoyed the untroubled path of the aging knuckleballer, he’d probably be in the Hall of Fame today, the way Wilhelm coasted into it. But just as quickly as he became Wilbur Wood, he stopped again. He took a comebacker to the knee and fractured it; weeks before the end of the season, he slipped on a patch of wet grass and broke it again. When he did return to action the next year, he admitted that he wasn’t himself. He kept bracing for that next hard hit, getting his glove up a little too quickly, letting go an instant too fast. His knuckleball suffered, and before long, it was all over. He was one of the best pitchers in the league for nine years, four of them in relief. He didn’t last quite long enough to sear himself into the histories.