LOS ANGELES — Few have been spared in the raids. They’ve taken people who came to Southern California from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. They’ve taken people from garment shops, street carts, farms, packinghouses, taquerias, big-box stores, home-improvement stores, and car washes. They've taken a union president (since released) and multiple U.S. citizens. They’ve taken people from what feels like every zip code, from the far-flung Coachella Valley to the manicured lawns of Pasadena, which shut down multiple city programs on Saturday after people got taken from a local park, to the grimy streets of Hollywood, where masked agents targeted a Home Depot in the heart of the city—just off a freeway, two blocks from local TV news station KTLA, and pretty widely known as one of the easiest spots in town to find a day laborer.

The fear of more raids has bled into everyday life, and led countless people to stay home. Even if you aren't afraid, you have friends or family or coworkers who are, and it's impossible to avoid the constant warnings about the latest ICE raids springing up across social media. There is the sense of communities trying to stand up an immune system under duress, the better to warn vulnerable people in time.

Even my bus ride Saturday down to the protest outside Dodger Stadium just felt a little emptier than expected. It's not quite that nobody is here; this is the second-largest metro area in the United States, universally recognized as one of the world's megacities, and it is plenty crowded. Still, it's hard to ignore the sense of absence created by the disappearances, and the uneasiness that results from who is doing them: federal agents in unmarked vehicles who don't show their faces or give any identification, and who leave behind no way for people to find where their loved ones have been sent.

Those disappearances were part of what brought more than 100 people to protest just outside Dodger Stadium. The Dodgers are a beloved part of Los Angeles culture, and a central tenet of the city's sense of itself. Yes, there are other sports teams, but none embodies LA and how Angelenos put themselves out into the world quite like Dodger blue. The Lakers are Hollywood's team, all glamor and global stars, with pop culture royalty sitting courtside. The Kings are beloved, but niche. The Sparks have, sadly, stunk. The NFL teams are new, the soccer teams are even newer, and the Clippers are, well, the Clippers.

But the Dodgers? That's Los Angeles, baby. They never left Echo Park for the suburbs or downtown or tried to turn the area surrounding their stadium into some kind of entertainment megaplex. They feel local; if you live on the east side, you can get to a game easily by way of a short drive or public transit, and a whole lot of people still go on foot. Sure, they've had stars, but at various points in history, the most famous person associated with the Dodgers was Vin Scully, a man who was mostly a voice on the radio, and then on TV. Until recent years, going to a regular-season game was even pretty cheap; all you had to do was buy nosebleed seats and bring your own food. It's the Dodgers' interlocking LA logo that every other team in town borrows and reprints in its colors, it's the Dodgers logo people get tattooed, and it's the Dodgers logo that everyone throws up with their hands when they get on camera.

This is not an accident. The Dodgers have marketed themselves as the community's team, and their history and that of Los Angeles tend to rhyme—the team that broke the color line in MLB by signing Jackie Robinson, although Robinson never played a game for the Dodgers in his birthplace. The team's legends include Mexico's Fernando Valenzuela (at the height of Fernandomania, more than double the amount of people listened to Dodgers broadcasts in Spanish than English), Korea's Chan Ho Park (the first Korean-born player in MLB history and still massively famous in his home country), and Japan's Hideo Nomo, all of whom became stars with the Dodgers, all from countries with strong ties to LA's immigrant communities. The team's biggest star right now is an immigrant, too. Their bond with LA's Latino community is undeniable; as Gustavo Arellano wrote recently in the Los Angeles Times, the team has "fostered a Latino fan base unlike any other in U.S. professional sports."

It was a very diverse group at the Saturday protest, but nearly everyone that I spoke to was Latino, and they all talked openly about how important the Dodgers are in their community, and how embedded Dodgers fandom is in the culture, with generation after generation growing up going to Dodgers games and rooting for the team. "It feels like they are family," Josue Pivaral told me, pointing out that right behind him were Dodgers advertisements for their upcoming Hawaiian shirt night, a Yoshinobu Yamamoto bobblehead giveaway, and the recently held black heritage night. The team's near-total silence about the raids, he said, "feels like a betrayal." As Ruben Pivaral put it, it's not like they wear clothing with the logo for the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce when they travel.

Not too long after the raids ramped up earlier this month, rumors swirled around LA social media about the Dodgers lending out their parking lots to federal agents. But the Dodgers stayed silent. That silence felt louder as both of downtown LA's professional soccer clubs, LAFC and Angel City, issued statements and had supporter sections that took action by going almost completely silent during games and bringing protest signs. I was at the first Angel City game since the raids began, and it was genuinely strange to be at a game with no supporter chants and drums to lead the way. When the supporter section did chant, near the end of each half, it was either "chinga la migra" or "ICE out of LA!" Members of the LAFC supporters group drummed in LAFC gear at the "No Kings" protest downtown, while Angel City is selling a T-shirt that says "Immigrant City Football Club," with net proceeds going to Camino Immigration Services.

Meanwhile, the Dodgers told the singer Nezza to not come back after she sang the national anthem in Spanish—a version commissioned by the U.S. government, no less. They barred a fan who brought a sarape, and they just kept on saying nothing, beyond manager Dave Roberts's brief words that the raids were "unsettling." Before Thursday's raids, only fan favorite Kiké Hernández and Spanish language broadcaster Jaime Jarrín had issued any statements of substance about what was happening.

So I wasn't surprised when protestors flooded Dodger Stadium last Thursday, after footage showed the federal agents from the Home Depot raid heading over there. The organization's strategic silence had by then come to feel like something much more pointed. The Dodgers issued a statement saying they had denied the agents entry, although the reality is more complicated; photos showed the same vehicles from the Home Depot raid at Dodger Stadium, and one Echo Park Rapid Response community member told the Los Angeles Times that a CBP officer told her the agents brought the people there to process them because "we can’t do it in the Home Depot parking lot because the public makes it dangerous." That night, the team kicked out a fan who brought an "ICE Out Of LA" sign to the game, though they followed that on Friday with the announcement of a $1 million pledge toward helping immigrant families.

None of that stopped protestors from showing up on Saturday. Each person I talked to had the same message: Given how much the Dodgers have profited off the city's Latino community, they weren't doing nearly enough to show that they were willing to return that support in kind, especially after the team had already visited Donald Trump in the White House and said nothing about the erasure of Robinson's story from official government history.

"A million dollars is nothing for the Dodgers," Martha told me on Saturday. "It's bullshit!" Martha said she was Mexican American, first generation, and had lived in LA her whole life. She knew how much pride Latinos took in Dodgers baseball. After watching the Dodgers stand on the sidelines while Latinos were terrorized and kidnapped, she told me that she thought "you don't give a shit about your community, you just see dollar signs." Of course the Dodgers needed to do more, she said, because "you can't be neutral in this society anymore."

Despite the heat, the group out on Saturday kept spirits high. The crowd included all ages, even little kids who lived in a nearby building and came down to join. The crowd grew, but never got out of control; no law enforcement showed up, either. Most of the noise was car horns honking in solidarity. One car drove by with a giant banner on the passenger side that read, "Dodgers Must Say No ICE." This being an LA protest, the most popular song played was "FDT"; Micheladas, hot dogs, and agua frescas were for sale. The signs were creative: "Tangerine Tyrant," read one; another said "Trump Don't F*ck with the Streets," which appeared over an image of the entire Sesame Street gang dressed like protestors.

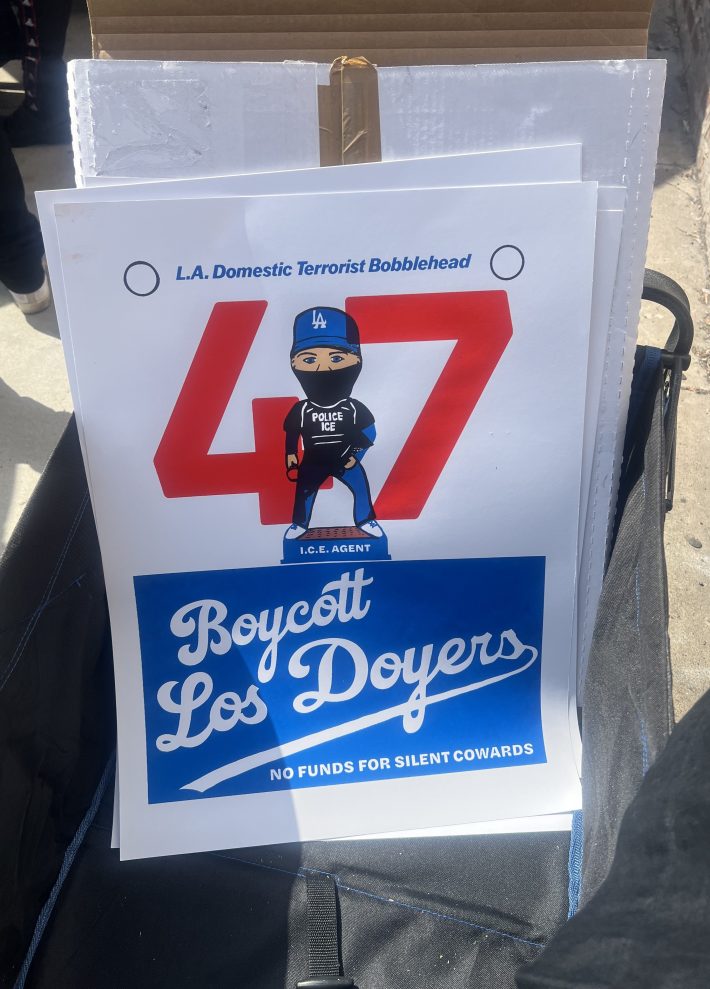

Gilda Posada brought signs that read "Boycott Los Doyers," followed by "No funds for silent cowards." The sign featured a riff on a bobblehead, but dressed like an ICE agent, its face almost completely covered but for the eyes. "We bleed blue—and right now LA is bleeding and they are staying silent," she said. And that $1 million? "We deserves a million dollars for every day they stay silent." All that talk about community? "If they say it's about community, here we are!" Posada brought 100 signs with her, and they were very popular. By the time we spoke, just a few were left.

I've lived in LA for more than a decade now, and I've never seen the city like this. This felt different than the fires or the floods, more ominous. I asked Posada about that, and she told me that she had felt this before, during raids in the 1990s. That round of raids, which followed another in the 1980s, led to the California Republican party backing Proposition 187—a 1994 ballot measure that sought to bar undocumented people from using taxpayer funded public services, including public schools. The measure passed, but it was later struck down as unconstitutional by a federal judge; the backlash helped transform California into the Democratic stronghold it is today. Those words on the Statue of Liberty saying "Give me your tired, your poor/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free?" A whole lot of Californians and Angelenos believe in that, and they are vigilant about protecting it. Since Prop 187, California has declared itself a sanctuary state, expanded health insurance access to low-income people regardless of their immigration status, and elected just one Republican governor, Arnold Schwarzenegger—an immigrant.

I haven't gone to a Dodgers game all season, because even before the raids began, the tickets are just too damn expensive. I went to my first game of the season on the same day as the protest; some friends had invited me weeks earlier, before the raids started. Walking through Dodger Stadium, with its giant mural paying tribute to Valenzuela, its many reminders about Robinson, and its incredibly diverse fanbase, its Spanish-language music between innings, while clutching the Ice Cube bobblehead that was that night's giveaway, I could see why people would be reluctant to quit the team. It felt that same way that Disneyland makes you feel as a kid; everything is orderly, everything makes sense, and everything is magic. It's how you might want the world to be—legible, safe, inclusive, good.

That feeling has always required a certain sanding off of the harsher truths in team history. Under all that order, quite literally, are the Latino communities that were razed to build the stadium; for all that happy diversity, there are the decades it took them to retire Valenzuela's number, and now that conspicuous institutional silence on the raids. The union president who was arrested by law enforcement? His union represents Dodger Stadium employees, who only got their most recent contract after threatening a strike. As L.A. Taco's Memo Torres put it, talking about "the big blue elephant in the middle of the city," Dodgers games are getting more expensive, their fanbase is being terrorized by ICE, and "the Dodgers now are an organization that's just focused on money and their own personal interests."

Even the Ice Cube bobblehead's packaging couldn't tell the full story of how and why such an item came to exist. It mentions Ice Cube performing before Game 2 of last year's World Series, and that was a nice moment, but that's not what first rocketed him to fame—the answer there was his role in the seminal Compton rap group N.W.A., one of The Most LA Acts imaginable, and also the one that performed "Fuck Tha Police."

But dammit if the illusion isn't so tempting despite all that. I don't doubt that everyone in the crowd, minus the tourists, knew about the raids. Many probably wanted and needed the escape of going to a Dodgers game, to watch a good baseball team play and share a sense of community with your fellow fan, or just to feel normal for a few hours. People in LA want to love their baseball team; even at the protest, one popular chant was "Do better Dodgers!" led by a young girl who got the bullhorn. The Dodgers know all this, and like any corporation would, they take advantage of that. They know they just need to do the minimum to keep people coming; they know that there is no percentage in doing more than they need to do.

Immigration is one of the stories the U.S. tells about itself—my own family immigrated here from the shtetls of eastern Europe, and I'm just the second generation born here on my father's side; you can probably tell a similar story about your family. But freewheeling and greedy corporations are another American story, from Standard Oil's monopoly, to the Pacific Gas and Electric Company poisoning the water around the California town of Hinkley, to the subprime lending crisis. Angelenos want the Dodgers to acknowledge and support one American story, the one with all of us in it. The team has done that in the past with the easy stuff, heritage nights, Pride nights, themed hats, and the like; it has not always been seamless, but they have done it.

And now vulnerable members of the community are being whisked away by masked men, with no due process and no accountability and no end yet in sight. As idealistic as it might sound, of course so many Angelenos want the Dodgers to rise above the calculation that defines corporate American history and stand up for the immigrant city in which they play, and in which they are so deeply embedded. It's a reasonable thing to want, and not remotely too much to ask. Whether the Dodgers will rise to that challenge remains to be seen.