Last year, a battle began in Portsmouth, N.H., over whether to use artificial turf on the athletic fields. Proponents argued that grass fields were hard to maintain, especially after a rainfall, and artificial turf would allow for most consistent use. But the drawbacks outweigh the benefits: Artificial turf, usually made from rubber and synthetic materials, often contains per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Exposure to certain levels of these "forever chemicals" can lead to health effects such as an increased risk of cancer, fertility problems, and damage to the immune system.

Portsmouth had already been dealing with high levels of PFAS in its water, due to a firefighting foam that had been used at a now-closed Air Force base. With this in mind, the city sought out a vendor who promised that the installed turf would be free of these chemicals. The project was approved in 2019, and the field opened two years later. Within months of opening, the local environmental group Non Toxic Portsmouth found in an independent test that the field contained these chemicals after all, a finding later confirmed by the city. Despite this, the city council voted to keep the turf, in part due to support from local students.

Across the U.S., places like Portsmouth are confronting the same question: Do we use artificial turf or ban it? In Martha’s Vineyard, the area’s planning board and a local high school have entered a legal battle over the surface. Bills have been filed this year in Connecticut and Massachusetts to ban its use. Boston successfully banned the installation of any new artificial turf on its public fields last year. Artificial turf may cut costs, but it’s bad for the environment and bad for those who play on it. It’s time to get rid of it.

According to Dr. Sarah Evans, an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Medicine and Public Health at the Icahn School of Medicine, artificial turf poses three primary health risks: exposure to forever chemicals, burns caused by excessive surface temperatures, and a higher rate of physical injuries.

“Artificial turf is made up of a number of different chemicals, including chemicals that have been linked to cancer, like benzene, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons; chemicals that are toxic to the nervous system, like lead; and chemicals that interfere with reproduction, like plasticizers and other hormone disrupting chemicals,” Evans told me. “You can breathe those chemicals in, you can encounter them through the skin, and they might get absorbed through the skin, but we also see a lot of cuts and abrasions that happen on turf. So then you have open skin, which can even further increase the ability of chemicals to get absorbed into the bloodstream.”

Additionally, accidental ingestion is a possibility, and indoor fields with less ventilation make airborne exposure to these particles a greater issue. The presence of these chemicals elicited concern earlier this year when the Philadelphia Inquirer tested pieces of old turf from the demolished Veterans Stadium and found the presence of 16 different PFAS. Six former Phillies players who played during the time of this turf's use died of the same type of brain cancer, all before the age of 60. In response, the team released a statement saying it had consulted several brain cancer experts who said there was no proven link between the turf and the deaths.

There is plenty of evidence demonstrating the harms of forever chemicals, but proving a specific link between artificial turf and detrimental health outcomes is difficult.

“One challenge with doing these studies is that many of the diseases that are associated with exposure to these chemicals take many years to develop,” Evans said. “There is a federal study that one of the goals of that study is to look at exposure characterization. But one thing that can be done is to look at the chemicals that are actually in the body immediately after play on turf. And so that’s something that the federal study is looking at and will hopefully release data on.”

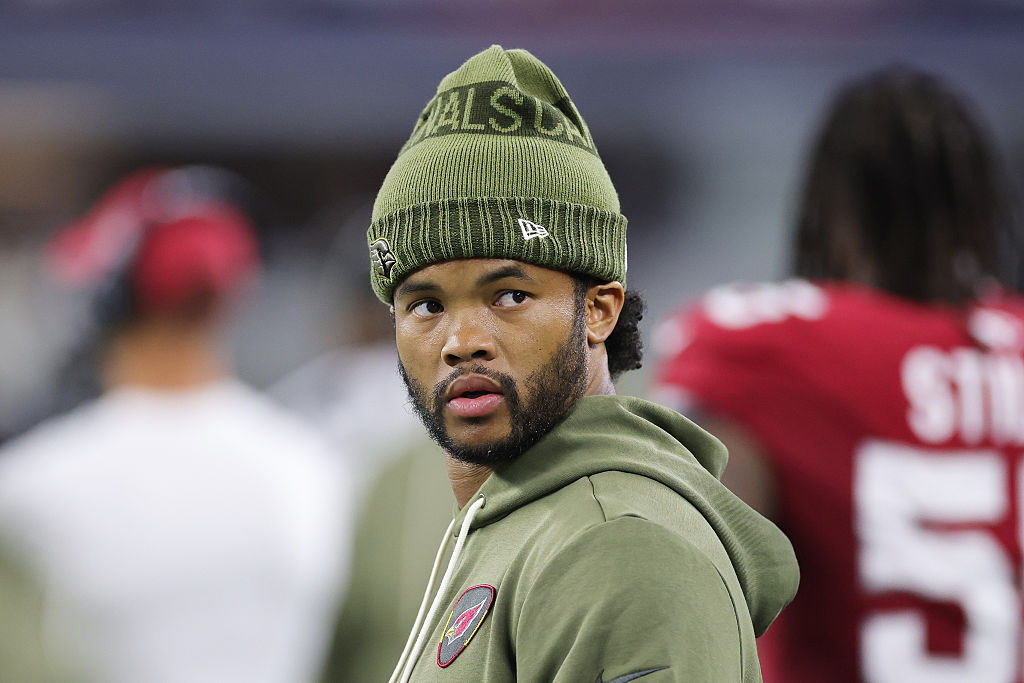

Perhaps due to this lack of data on chemical harms, most arguments for eliminating artificial turf focus on the risk of physical injuries. This risk is why NFLPA president J.C. Tretter spent last year pushing for natural grass to replace turf, citing the higher rates of non-contact lower-extremity injuries, specifically involving the knee. Such a move by the NFL would also lead to change within Major League Soccer: At present a handful of MLS teams use artificial turf, because they play their games in football stadiums.

Whether artificial turf contributes to injuries is contested. Some research has suggested the risk varies by sport: Some studies from soccer show no significant risk difference between turf and natural grass, while other studies that look at professional and college football show an increased risk for lower-body and knee injuries respectively. On the other hand, a recent study looked at the risk of injury for high school students across sports and found that athletes were 58 percent more likely to sustain an injury on artificial turf.

“I think one of the things that we’re seeing is that there’s increasing pressure in communities that have high school teams to play on what they perceive to be the cutting-edge, high-tech, artificial turf fields,” Evans said. “And so the injuries that you see at the professional level are trickling down to the lower levels, to high school communities.”

As with most things bad for our health, artificial turf use has troubling environmental impacts. One issue is its inability to absorb water like natural grass does; this leads to rainwater runoff, which can then carry chemicals into waterways. One study investigating the water retention properties of artificial and natural turf lawns found runoff carrying plastic fibers away from the former. In January, researchers in Japan published a paper noting rubber tips from an artificial turf field draining into surrounding sewer pipes. The researchers placed some of these tips into goldfish tanks and found that the goldfish readily ingested them—indicating yet another potential source of chemical exposure, not only to players on the field but to surrounding communities and wildlife.

Municipalities and homeowners increasingly are turning to artificial turf as a replacement for natural lawns, particularly in places where climate change and water-use constraints make grass-growing difficult. While this is put forward as a solution to conserve water in places without much rain, it creates new problems even in the relative absence of runoff concerns: Insects have difficulty burrowing in and out of the soil, which then affects other creatures in the food chain.

Despite all these harms, proponents of artificial turf often put it forward as a solution with claims of superior durability and longevity. However, these turf fields can only last about a decade and produce a huge amount of waste once they need to be replaced. Solid-waste industry analysts reportedly estimate that 1-4 million tons of this waste will be made in the next decade—waste that, again, contains problematic chemicals. Artificial turf manufacture also produces carbon emissions, and turf generally is not recyclable. A Pennsylvania turf-recycling plant announced in 2021 has yet to open, and has instead been given notice for violating environmental standards due to the accumulation of material. Whatever time or upkeep savings turf may offer are more than offset later when dealing with the sheer amount of waste.

For Evans, the policy implications are clear: “Communities should at a minimum impose a moratorium, if not a ban, on installing these products.”

As we deal with the effects of climate change impacting every aspect of our lives, the pressing challenge is how to design alternatives or change lifestyles to improve health and environmental effects. We try to find “greener” solutions problems, and then it turns out that those solutions aren't actually green at all, or might be better in the short term but more harmful over the long run.

While not every place might have the climate of Springfield, Mass., it may serve as a useful model. The city has implemented an organic grass field program that ensures public fields are maintained naturally and without the use of harsh chemicals. Since launching the program in 2014, the number of fields have doubled and usage has generally increased, according to the Toxic Use Reduction Institute at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. Grass fields may require routine maintenance, and there may be instances in which play has to be delayed, but these costs are minor compared to the benefits of less exposure to PFAS.

The artificial turf bans being debated in places like Portsmouth represent a step in the right direction. In many different ways not exclusive to municipal sports, we have sacrificed the climate and public health at the altar of convenience. These decisions will catch up with us, but there is an opportunity to change the outcome for the better. It's not too late to take restorative action and ban turf.