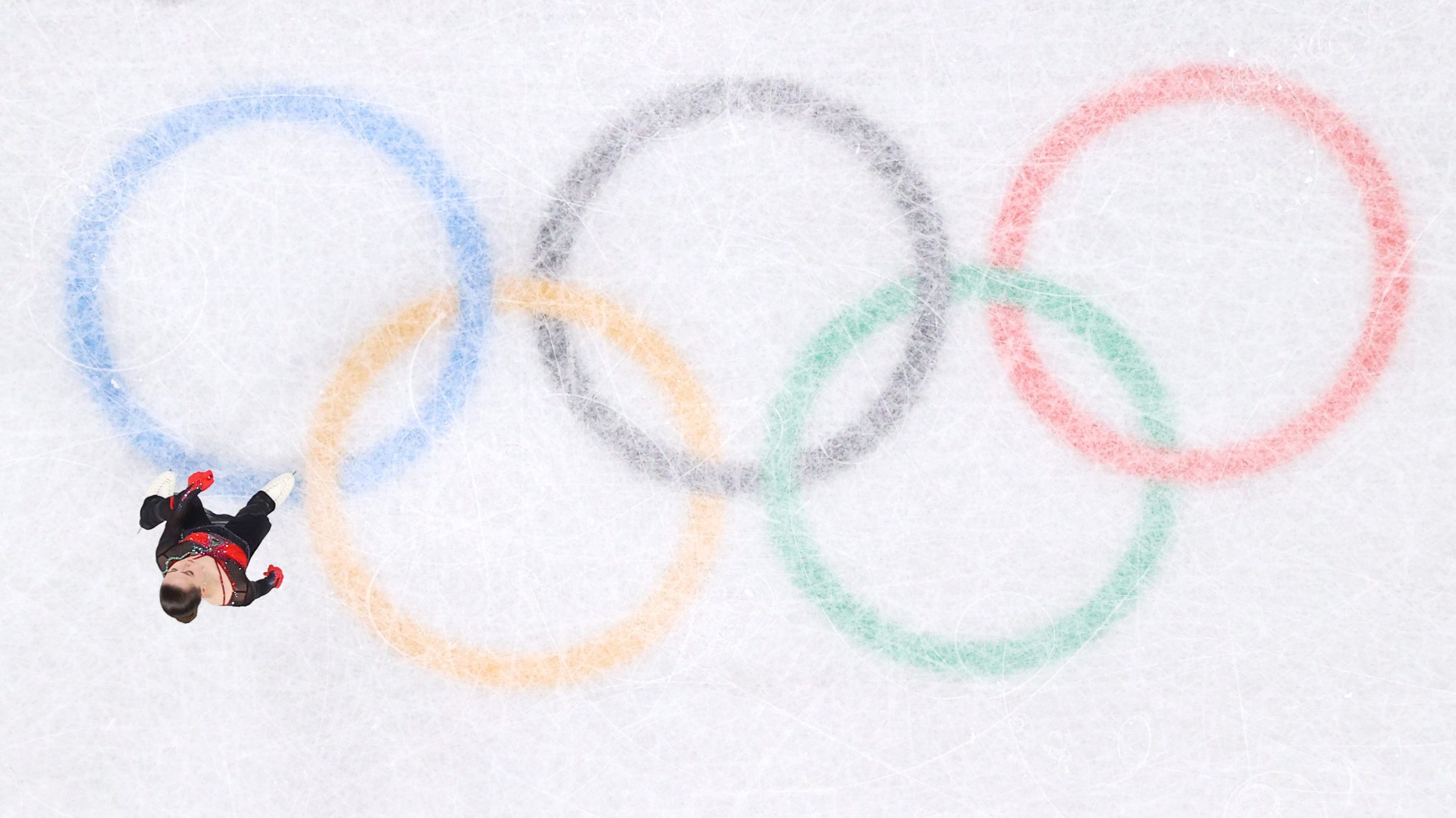

Everyone was so excited that Sunday night just two weeks ago, or at least I was. Figure skating is one of the Winter Olympics' marquee events, and this was expected to be one of its greatest moments. As the end of the team event drew near, 15-year-old Russian skater Kamila Valieva took the ice, resplendent in red and black, a sequined snake's head perched by one of her shoulder blades, her hair coifed in a perfect bun. Her music began, the perpetual figure-skating favorite, "Bolero," and off she went. Within minutes, Valieva was expected to become the first woman in history to land a quadruple jump at the Olympics.

"She has lived up to every expectation so far in her career, but there is more to do," said NBC's Tara Lipinski, who herself was 15 years old when she won her Olympic gold medal in figure skating. "If she lands this quad, we will be talking about this exact moment for the next 100 years."

As the familiar march of "Bolero" went on, Valieva leaped into the air and spun four times, a quad salchow. She spun not with her arms tucked against her body, but above her in the air, making the jump even more difficult and more visually pleasing to even the casual viewer.

"Yes!" proclaimed former Olympic skater Johnny Weir on the broadcast.

"Stunning!" Lipinski chimed in.

"First ever," commentator Terry Gannon reminded us.

It was the type of moment the Olympics are supposed to give us, filled with grandeur and wonder at what the human body and spirit can do. A girl from Russia with a seemingly superhuman gift had arrived on the world stage, beautiful as a ballerina, strong as steel, prepared to share her gift with all of us and make history, too. And I must admit, I enjoyed it. I was so happy for Valieva. I was happy for women's figure skating. I was happy because it always feels good to see what you believe to be greatness achieved.

And then it all came crashing down. For the same reasons it always does. The same reasons I should have known. The fantasy never matches the reality.

A few days later, USA Today's Christine Brennan broke the news that Valieva had tested positive for a banned drug, later revealed to be trimetazidine. The sample that tested positive was from late December, around the time of Russia's national competition, but Russia's anti-doping agency, RUSADA, said it didn't get the results back from the lab until Feb. 8. (No surprise, RUSADA said the delays are the lab's fault, while the lab said the delays were RUSADA's fault.) RUSADA suspended Valieva, but she appealed it and RUSADA granted her appeal. Three different organizations then appealed that decision to the Court of Arbitration for Sport.

The CAS said that Valieva could skate because removing her from the competition would cause her "irreparable harm." They also seemed to be leaning, quite a bit, on a quirk of anti-doping rules, which said that at 15 (but not 16) Valieva was a "protected person.”

But protected from what? After Valieva failed to medal following a disastrous free skate, the entire Russian team imploded on live TV. Valieva's coach, Eteri Tutberidze, berated Valieva the moment she got off the ice. Her teammate, silver medalist Alexandra Trusova, erupted in angry tears at being denied gold despite landing an unprecedented five quads. And the actual gold medalist, Russia's Anna Shcherbakova, sat alone, clinging a teddy bear. Days later, amid all the chaos and backtracking and angry statements emerged stories that weren't a total surprise to anyone who has kept an eye on women's figure skating. Many have known that Tutberidze, who coached all three Russian skaters at the Olympics, has a long history of abusive behavior toward her athletes. As Rita Wenxin Wang explained in Slate:

Her methods are no secret. The Eteri girls talk openly about not being able to drink water during competitions. They do their best to delay puberty by eating only “powdered nutrients” or by taking Lupron, a puberty blocker known to induce menopause. They are subjected to daily public weigh-ins and verbal and physical abuse. And they compete while injured, huffing “smelling salts” while wearing knee braces and collapsing in pain after programs.

Every year, a new, younger Eteri girl emerges on the scene while others retire, at age 17, 16, or even 14. Skating fans call this the “Eteri Expiration Date.”

It is impossible to read about Tutberidze and not think about another infamous coach of female athletes, Bela Karolyi, who lorded over women's gymnastics in the United States for decades, producing winners at an extremely abusive cost. But the comparison to Karolyi somehow felt lacking to me. Because singling out the Karolyi would be to ignore that women's sports, especially gymnastics and figure skating, have for decade after decade after decade after decade had many, many, many Karolyis.

Bela Karolyi featured prominently, though not exclusively, in Little Girls in Pretty Boxes: The Making and Breaking of Elite Gymnasts and Figure Skaters by Joan Ryan. The book came out in 1995. I was 14 at the time, and about as far away from Olympic glory as possible: I had never taken a gymnastics class, or a figure skating class, and had, and still have, so little flexibility in my hips that even touching my toes without a warmup can be a bit dicey. But if you had given me a magic wand and said, here, teenage girl, it can make you anything, I would have begged that magic wand to make me a gymnast or a figure skater, though I probably leaned toward figure skater. This was the mid-1990s, the peak of figure skating's popularity in the United States. This was two years after Kristi Yamaguchi won gold, one year after Nancy Kerrigan won silver. It would be perhaps too bold to say every girl in the United States wanted to be a figure skater or a gymnast, but a whole lot of us did.

This wasn't on accident. For most of my childhood, the most regular examples of women as athletes on my TV were figure skaters and gymnasts. There was no WNBA until 1996. There were professional women's soccer leagues, and they kept folding until the NWSL. Women weren't paid to play hockey in the United States until 2015. There is still no prominent women's pro football or baseball or softball. This was what women athletes looked like, we were told, and these were the ones you were most likely to see on TV. They were tiny and skinny with perfect hair and they could, seemingly, fly. When I think back to my '80s childhood, I can tell you what were far and away the most popular activities among my friends in elementary school: Girl Scouts, dance classes, and gymnastics. I did not do any of these and got so mad at my parents for it; it felt like they were robbing me of key pieces of my American girlhood, though I did eventually did get to do exactly one week of dance class.

And then came Ryan's book, a tour de force of reporting and writing that explored the physical and emotional abuse inflicted on gymnasts and figure skaters, all while they were still clearly children. That abuse manifested in eating disorders, permanent damage to their bodies, and, at times, death. There's Julissa Gomez, 15 years old when she was paralyzed while trying a Yurchenko vault, which she did, despite not being very skilled at it, at the urging of her coaches who wanted her to get its added points. She died three years later due to complications from her horrific injuries. And there was Christy Henrich, a former gymnast who died at the age of 22 from multiple organ failure due to anorexia and bulimia. Though Henrich and Gomez were the most extreme stories in the book, and both from the world of gymnastics, there were plenty of harrowing accounts from young women who had chased their figure skating dreams as children, only to be left with broken bodies, disordered behavior, and regrets.

I didn't read the book when it first came out. In my defense, I was in middle school. And you didn't need to read the book to know about it because that's how huge it was. At one point, Ryan appeared on the Oprah Winfrey Show to talk about it—and this is back when Oprah had an estimated viewership of 48 million people. There even was a TV movie. Everyone talked about this. Later editions of the book would include added material about the all the steps being taken, especially within gymnastics, to ensure a Julissa Gomez or a Christy Henrich would never happen again.

I did buy a copy years later, in 2017, during the early stages of the Larry Nassar scandal. Nassar sexually abused hundreds of athletes, mostly female gymnasts, under the guise of medical treatment, all from his lofty perch as doctor to United States women's national gymnastics team. I dog earned certain sections that stood out to me, even though it was 2017 and this book already was 22 years old. I reached for my copy again after the Valieva news broke, and returned to those dog-eared pages. They rang so true in 2017, and they still haunt me now. I re-read them, over and over again, trying to figure out if anything had changed beyond the names.

Like when Ryan reflects on calls for age limits in the Olympics. In gymnastics, the limit is 16. (There was none when the book came out.) In figure skating, it's 15, but a higher one could be coming. Figure skating analyst Jackie Wong reported on Tuesday that in June the International Skating Union Congress will vote on a proposal to raise the age limit for senior events to 17.

The argument against such limits is that it's unfair to put a ceiling on children's potential, unfair to tell them what to do with their lives. Which, Ryan quite clearly points out, is bullshit. I don't believe that age limits alone will end abuse—as former athletes have pointed out, age limits often are sold as a quick fix that ignores the need to tear apart corrupt systems and remove the bad actors—and the age limit in gymnastics hasn't ended abuse. But I do agree with part of Ryan's logic here: Society places restrictions on children for their own safety all the time. If we can limit the number of hours a child can work in a factory, why can't we limit the amount of hours a child can train in a gym? After all, training for a sport is work.

"Restricting children from certain activities is hardly a revolutionary concept. Laws prohibit children from driving before sixteen and drinking before twenty-one. They prohibit children from dropping out of school before fifteen and working full-time before sixteen," Ryan wrote. "In our society we put great value on protecting our children from physical harm and exploitation, and sometimes that means protecting them from their own poor judgement and their parents' poor judgement.

"No one questions the wisdom of the government in forbidding a child to work full-time, so why is it all right for her to train full-time with no rules to ensure her well-being? Child labor laws should address all labor, even that which is technically non-paid, though top gymnasts and figure skaters do labor for money."

Another page I dog-eared: When Ryan wrote about why the gymnastics federation wasn't making any progress on the health and safety front.

The fallacy of the federation's safety and health programs is that the federation has no teeth. It can dispense the best advice in the world to the coaches and athletes, but it can't make them follow it. The federation can't ban a coach unless he has been charged with a crime. Repeated injuries to his gymnasts, abusive language, ignorance of eating disorders—none of these are grounds for expulsion from the federation. [USAG's] Kathy Kelly can talk informally to a coach who has aroused safety concerns. But the federation can't put limits on the hours a coach can train a girl or the number of repetitions he can demand. It can't require medical care on-site at gyms. It can't order coaches to throw out their scales.

So where is the safety net if the coach is damaging the gymnast and the parents have neither the confidence nor the brains to stop him? "There is none," concedes education and safety director Steve Whitlock.

In 2022, plenty of athletes could easily tell you that there is still no safety net for them. SafeSport, the organization created by Congress to ostensibly investigate sexual abuse in sports, is, at best, underfunded, overworked, slow to take action, and can't even guarantee that a suspension, once issued, will be upheld. It has been criticized by athletes in gymnastics, fencing, taekwondo, and weightlifting. Beyond that, the organizations that oversee these sports remain as riddled with conflicts of interest, corruption, and opacity as ever. Take, for example, the athletes commission for the Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique, which oversees gymnastics. This is, in theory, the body that would hear complaints from gymnasts. Yet FIG's athletes' commission chairperson in 2019, Liubov Charkashyna, said that she thought many of the Larry Nassar victims were lying for money. (Charkashyna, per FIG's website, does not appear to be the chair anymore.)

The details go on in Ryan's book. There are the athletes hoarding food and hiding it from their coaches. There's so much discussion of disordered eating, of anorexia, of bulimia, of weigh-ins, of coaches harping on every pound lost or gained. There's Bela Karolyi, dubbed "the high priest of insensitivity," and the many coaches who mimic him because they share his belief that yelling, screaming, insults, training while injured, and constant weight monitoring are the best ways to coach. There are parents who begin to believe that their child's success is their own, and push their children long after it is clear they do not want to participate anymore. I dog-eared a page where the father of a former gymnast calls himself "a failure as a parent."

"We know that our consumption and disposal of these young athletes are tantamount to child exploitation and, in too many cases, child abuse. But we still rarely ask what becomes of them when they disappear from view. We are reluctant to watch them parade past us with their broken bodies and spirits," Ryan wrote in 1995. "We want our pink ballerinas inside the jewelry box, always perfectly positioned, perfectly coifed. They spin on demand without complaint. When one breaks, another pops up from the next box. To close the lid is to close that part of ourselves that still wants to believe in beautiful princesses and happy endings."

Ryan's book discusses frankly what sometimes gets left out of discussions about abuse in figure skating and gymnastics. Yes, abuse can happen in any sport, and it does. But in women's figure skating and gymnastics, the power dynamics are influenced by one additional factor: The athletes start high-level training at a very young age, when they are legally children. As Brendan Schwab, the executive director of the World Players Association, explained on an episode of the Blind Landing podcast, it's pretty obvious that a solution to athlete safety, including stopping abuse, will involve creating an organization that athletes run and control, completely independent of the federations, that can fight for change. But this becomes more complicated in sports like gymnastics and figure skating because the athletes are children.

"The athletes themselves are inherently vulnerable, children athletes are more so … but I also don’t think it’s necessarily feasible for thousands of children athletes to get organized," Schwab said. "And this is something that I think the sports world is struggling to deal with."

There is another idea, one that's come up a few times over the years about how to fix youth sports in the United States. It's Norway's Children’s Rights in Sport document, first adopted by the country in 2007. It's a truly radical document; per The New York Times in 2019, it at the time was the only document like it in the world. Here are just some of the rights it says all children in Norway have:

- The sport activities are organised according to the children’s needs and that all children are included in the sports clubs regardless of their ambitions and needs.

- Activities are offered without any differential treatment and without regard for the child’s and its parents’ gender, ethnic background, faith, sexual orientation, physical development and disabilities.

- The sports clubs develop a wide and diverse range of activities and schemes.

- Coaches, managers and parents become even better at cooperating on facilitating activities for children.

- Good communication between the various sports, the parents and the community on which values Norwegian children’s sport shall be based on.

That's only from one page. Other rights children have: The right to safety and security, the right to a sense of well-being and friendship, the right to be heard, the right to choose the sports they do, the right to choose how much they train, and the right to compete as much or as little as they want.

Just as telling is what children are not allowed to do. Per the Times:

No national championships before age 13. No regional championships before age 11, or even publication of game scores or rankings. Competition is promoted but not at the expense of development and the Norwegian vision: “Joy of Sport for All.”

Norway, with a population just more than five million, won more golds and more medals than any other country in this year's Winter Olympics. This is not to say that this way, the Norwegian way, is the only path toward ending abuse in sports. But it is an idea. Why can't other countries like the United States at least consider adopting some of its principles? Why did this never come up in the endless congressional theater after the Larry Nassar scandal? There's no point in remaining loyal to the current system—an alphabet-soup of non-governmental bodies all operating as their own insular and broken fiefdoms, hoarding their power and protecting their friends, all while the USOPC leadership sits around, signs some Team USA marketing contracts, and counts the medals. None of this benefits athletes, yet the U.S. clings to it as if it is the only way, when really it's just all we know.

Walking away from the status quo would require a reframing, not just of what we expect of our athletes, but of how we view teenagers and little girls. What do we expect of them? What do we want from them? Why do I still associate quintessential American girlhood with these sports, and their long trails of physical and emotional abuse? I think often about why women, myself included, don't speak up more. Men ask me this all the time. But then I think about what the culture of these sports must teach us, which is reinforcing what the world already tells us, and then it suddenly feels so much less like an accident that these sports are this way.

Though the details were new—a woman named Tutberidze, not a man named Karolyi, the yelling in Russian instead of English, the NBC cameras capturing it all—they also felt familiar. Because they were. Those heartbroken Russian girls came from the same world as Julissa Gomez, Christy Henrich, Dominique Moceanu, Ashley Wagner, Adam Schmidt, Craig Maurizi, Bridget Namiotka, Jennifer Sey, Riley McCusker, Emily Liszewski, and the more than 500 survivors of Larry Nassar. Those scenes after the free skate made me think of the gymnasts who used to train at the gym of former Bela Karolyi protégé Kim Zmeskal-Burdette, who became a coach, just like her mentor, and who years later would have multiple former gymnasts describe what sounded like her mimicking some of Karolyi's behavior.

The names change, the dates change, and the countries change, but the fundamental power imbalances—and the way those in power abuse their positions to hurt children and teenagers—do not. It happens so frequently, so often (a story about abuse at a Pennsylvania gym broke while I was writing this), that it is simply a part of everyday sports culture, as woven into American life as the Super Bowl and apple pie, and nobody in power is terribly bothered by it. You could say it's normal, even banal.

As good as those in leadership are at issuing angry statements, their actions belie a deeper truth: Everyone has known for decades the abuse endemic in women's figure skating and gymnastics and nobody with power is disturbed enough to actually do anything about it. The abuse and the permanent injuries and the eating disorders, they tell us with their actions, are by turns unavoidable, or tragic accidents—never systemic.

Like many Olympics before it, this one closed the figure skating portion with a gala. I love watching these galas. The routines are, no surprise, not nearly as technically difficult as those skated in competition. But I like to see what each skater, given free rein, chooses for their music, for their costume, for choreography. Already, far in the distance of my mind, were the horrors on display just days earlier. There was Yuzuru Hanyu, as ethereal as ever. Nathan Chen bounced across the ice, like pure joy. There was Alysa Liu, rocking out to Itzy's "Loco." There was Alexandra Trusova, transforming herself into Wonder Woman.

The second to last performance was the new gold medalist, Anna Shcherbakova, gliding across the ice to "Ave Maria," clad in all white, her arm sleeves transformed into wings. About halfway through, the spotlight on Shcherbakova grew darker, and her wings suddenly lit up, a sheath of soft white light. She was a 17-year-old angel manifested, gliding across the ice, utterly enchanting by design. But I couldn't feel the magic this moment was meant to impart, even if I could sense it creeping up in my mind. I kept thinking about Shcherbakova all alone, and Trusova's tears of rage, and Valieva's despondence, and the promises of an investigation, and the excuses being trotted out in the media for Tutberidze, like they've been trotted out by the press in so many countries for so many coaches before her. And I knew that this moment, the fantasy of an angel with her wings, was not worth it.

Correction (12:39 p.m. ET): This article has been updated to reflect that figure skating currently has an age minimum and the ISU vote would be to raise it.