This time last week, I had what I assume to be the average level of knowledge about Yoko Ono and her art: She screamed, she protested, she was a little too present in a project that wasn’t hers, and she continued creating art that advocated for peace even after watching her husband get shot right in front of her.

But in terms of what that art actually was, I would have had trouble describing or naming any of it. This struck me as a cultural oversight on my part, so I did what anyone would do and signed up to attend a two-day academic and artistic symposium celebrating her work in honor of her 92nd birthday.

As I entered the event, which I have since dubbed “Yokofest,” my mind was open. By the end of the two-day symposium, I was dizzy.

My intention was to figure out the legacy of Ono’s art. Her artistic career began about 75 years ago in the avant-garde scene in New York, and even as a person with a fairly high tolerance for “weird art,” I had no idea what to make of her multidisciplinary oeuvre.

It turned out, in fact, that I knew the least about her early work, which was based in conceptual performance art and not just music. Over the course of two days, I was mentally and emotionally blasted with a multidimensional view of her artistic philosophies and creation. I saw it. I heard it. I’m still not sure I like it.

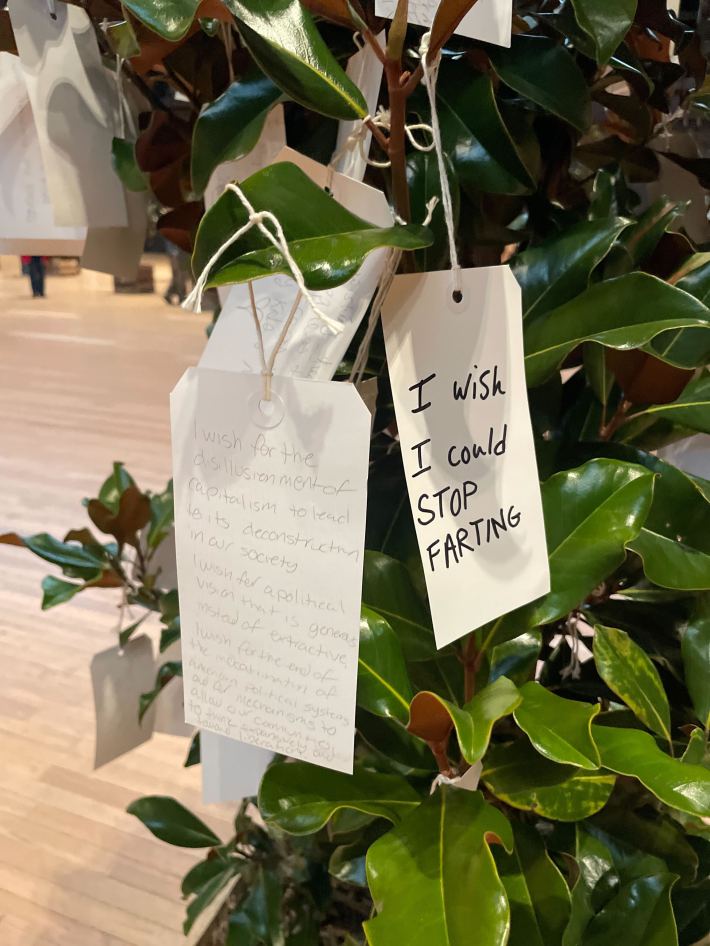

The event was centered around Wish Tree, a serial installation in which participants are encouraged to hang their hopes on the branches of living trees. Typically, as a reporter, I wouldn’t participate in an event I was covering, but I knew that the interactive element of Yokofest was essential to my understanding of her and her art.

Live trees were spread around an airplane hangar–sized space, with blank tags and pencils laid out for participants to write out their desires. The most common theme I saw amongst these tags had to do with Donald Trump and Elon Musk.

I appreciated one that said: “I wish for the singularity to happen soon.” Another one, written by a child, wished “that one day I will get two fluffy big dogs that lick me and like me.” A good aspiration if there ever was one.

On my tag, I wrote out a request that bordered on a brief manifesto:

“I wish for the disillusionment of capitalism to lead to its deconstruction in our society. I wish for a political vision that is generative instead of extractive. I wish for the end of the indoctrination of American political systems and for mechanisms to allow our communities to think expansively and toward liberation.”

Maybe it was supposed to be one wish per tag, I realize now. Anyway, I hung my tag next to one that said “I wish I could stop farting.”

Surrounding Wish Tree was an event packed with academic interpretations of her work and a few artistic performances. Her creative output and her life were thoroughly dissected, and my ultimate question after all of this was: What impact did she have on the people who consume art and are creating art now?

“From my perspective, she just kind of pushed the envelope at a very early stage,” said Paul D. Miller, who associated with Ono as part of the downtown New York scene in the 1990s. “That's what made her, I think, part of the DNA of our time.”

But Ono’s avant-garde work in the 1950s and 1960s was based in ephemerality and the self as art. She is not the sort of artist to leave paintings to a museum. It will live on—fittingly—in ways that are obscure and abstract.

A musician I met at Yokofest, jae m. author, a professional bassoonist who experiments with noise music, said they read Ono’s 1964 book Grapefruit last year and felt “at home” upon reading her short and strange instructions for methods of experimentation. “It made me remember that someone had been considering these concepts long before I discovered them myself,” jae said.

A nice legacy, but one that surely falls short of what the woman famous for saying “War is over, if you want it,” hoped her work might achieve. She presented peace as a form of action and evolution as a form of revolution. But the defining element of her art is one of passivity, and I struggled to resolve this contradiction in the abstract.

For me, the most informative elements of Yokofest came when I got to actually experience the performance, rather than think about it.

On the first day of the symposium, there was an event titled “Always Thinking about Cut Piece.” For those unfamiliar with Cut Piece, as I was when I entered the building that day, it is a demonstration Ono performed first in 1964, then multiple times throughout her career.

Ono would sit wordlessly in front of an audience wearing simple clothing and a blank stare. Next to her, she’d place a pair of heavyweight scissors. She remained still as members of the audience were invited to participate, cutting away her clothing bit by bit until she was often nearly undressed.

It is almost a little too heavy-handed that this performance foreshadowed how she would be ripped to shreds by the general public when she became a mainstream figure a few years later.

But when I walked into the room for what I expected to be an academic deep dive into the meaning of Cut Piece, I instead found Professor Julia Bryan-Wilson sitting cross-legged and silent on a stage with a pair of scissors next to her. We were about to experience, rather than interpret, Ono’s most well-known piece of solo work.

It was Bryan-Wilson’s first time performing Cut Piece. She wore a vintage silk dress by avant-garde fashion house Viktor&Rolf, an item of clothing that was meaningful to her, and held a blank stare that conveyed no emotion.

The experience was uncomfortable, as everyone in the room realized what we had to do. Earlier that day, Brigid Cohen, a fellow professor, had shown and examined Cut Piece in her own presentation. She stressed that the piece is auditory as well as visual, a concept I didn’t understand by watching an old and fuzzy video of Ono’s performance in 1964.

When Cut Piece was performed in front of me, I quickly understood what Cohen had described. Every sound in the room was palpable. A sneeze, a whisper, the sound of footsteps on the stairs of the stage, and the sound of the scissors that we used to strip Bryan-Wilson down to her undergarments.

After a few other people began to disassemble Bryan-Wilson’s garment, I took my turn. I walked onto the stage and grabbed the heavy scissors, cutting away an innocuous piece of her sleeve. I snapped the scissors shut as loudly as I could on every cut. I felt like I was violating this stranger, meaning that Ono’s message had reached me.

“My biggest fear was that no one would take up the invitation,” Bryan-Wilson told me. “I think I would have rather been injured by someone than just left hanging.”

It is inescapably relevant that Ono was a Japanese woman who demanded to be let into the avant-garde scene in New York just a few years removed from the end of World War II. She often felt stripped of her agency and power, so she used what she had: her body and the way other people perceived it. This included her vocal chords. She often screamed, wailed, and at times turned sounds we associate with sex into screams of horror.

She felt deep grief over both the attacks on Japan and the horrors of Japanese imperialism. She lost custody of her daughter, Kyoko, and didn’t see her again for 27 years. She watched her husband die and laid grieving in the bed they shared, trying to ignore the sound of heartsick fans blasting “Imagine” outside of The Dakota, trapping her in a loop of hearing her dead husband’s voice.

When I learned this final detail, and pictured Ono trying desperately to block out this music, I felt my chest tighten with sadness and anxiety. My eyes welled up and at that moment, I was the one who felt the need to let out a primal scream. (I did not. Even at Yokofest, that would have been inappropriate.)

I’m not alone in my sympathy for Yoko Ono. Over the last few years, there has been a strong effort by artistic historians and feminists to recontextualize Ono’s place in the pantheon of pop culture. She wasn’t a pariah, she was simply inconveniently present.

But even the backlash to the backlash feels to me like a strained effort. My opinion had been pushed and pulled by the boomers who hated her and the millennials who defended her (sorry, Gen X, I don’t know where you fall on this spectrum). I could no longer tolerate having my opinion shaped by the theories of others.

I’m my own person, dammit. I can decide for myself.

But I wondered, ultimately, what Ono had changed through her various artistic endeavors. I mentally ran through her list of successors: Sonic Youth, Lady Gaga, Marina Abramović, Björk, and even Jack Antonoff’s band Bleachers. Personally, I drew a line between Ono’s experimental sound and the work of Brian Eno, a minimalist.

Her instructions in Grapefruit remind me of the cards in Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt’s “Oblique Strategies” cards. They both give the reader suggestions on how to think out of their mental confines of creativity. (“Make an exhaustive list of everything you might do and do the last thing on the list,” one card declares.)

But Ono delivered a quieter influence well into her senior years. Miller recalls Ono attending small performances of art rock, electronica, new waves of avant-garde music, and the early experiments of hip-hop in the 1990s. Her curiosity never waned, and her presence at these small events gave legitimacy to the artists who were performing.

“When younger artists look up to you, it really gives a sense of what is possible,” Miller said. “So when Yoko would show up [...] it was like this electricity would go around the room. And everyone was like, walking on thin ice.”

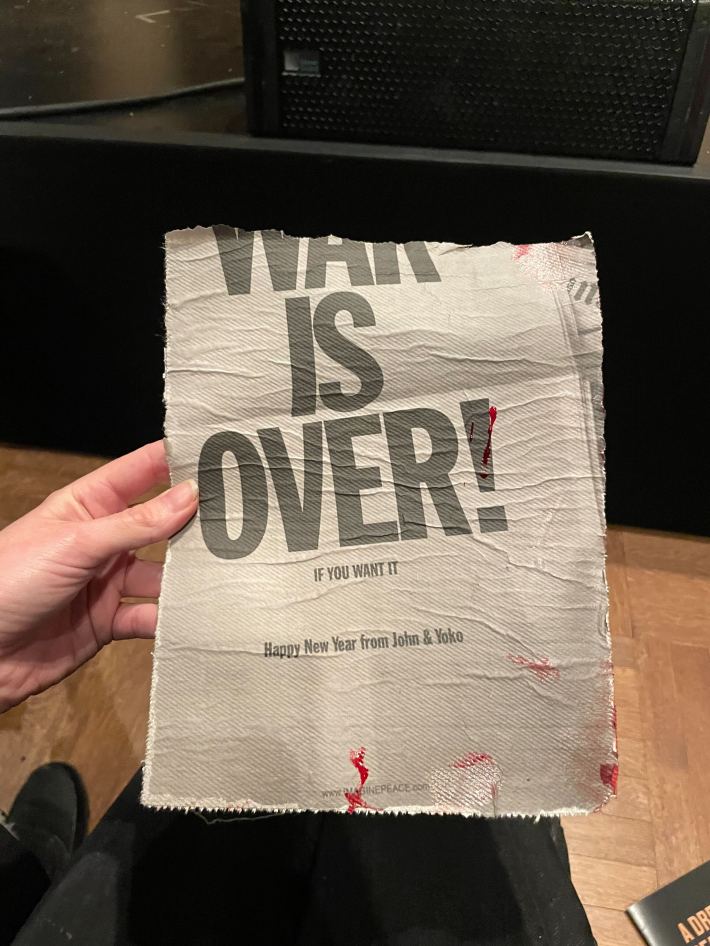

My final event at Yokofest—“WAR IS OVER (PAINTING TO BE DESTROYED)”—was meant to be provocative, but became its own sort of electric, communal experience.

Waseem Nafisi, a Brooklyn-based artist, presented an 6-foot-5 by 10-foot painting of an old photo of New York City, with reprints of Ono’s famous “War Is Over!” posters on the back. Just as soon as the painting was shown to the audience on an easel, it was tipped over onto the ground.

Nafisi sliced the painting off its frame and began tearing it apart with a knife, breaking it into 120 rectangles that audience members scrambled to claim. Typically, participatory performance art still keeps the artist as the conductor of the event. In this case, the whole audience joined in.

Two women went on stage to help Nafisi tear apart the painting. Lines formed to grab the tiles he tossed at the front of the stage. I heard people bragging about which portion of the painting they had nabbed.

The slice I took features part of an advertisement that now reads: “ON HER.” Honestly, I am pretty satisfied with that outcome, and I’ve ordered a frame to hang it in my home.

“Ono was with us,” Nafisi told me the next day. “It embodied the unexpected nature of what performance can do, and it blew my mind.”

Halfway through the destruction of his painting, Nafisi sliced open his knuckle and began dripping blood onto the backside of the painting. Production assistants who were probably thinking about liability issues rushed to get bandages. Nafisi kept going in spite of the injury, and the painting was completely disassembled in less than 20 minutes.

The final tiles of the painting were left at the front of the stage as Nafisi was led away toward a first-aid kit. Audience members scrambled to claim the last remnants of Nafisi’s work. They were not afraid of the viscerality of the experience. They went for the most avant-garde of the tiles.

“WAR IS OVER if you want it,” they presented proudly, sprinkled with the artist’s own blood.

My two days at Yokofest left me still undecided on the public value of her work, but something about the immersive voyage itself propelled me into a state of creative frenzy that seems oddly relevant to all of the art and information I consumed throughout the weekend.

Something about this experience catalyzed in me a magnetic urge to change something about the aesthetics of my own body. Self as art, self as art, self as art must have been running through my subconscious as I rode the train back toward my home.

I racked my brain for what I could possibly do to myself at nearly 9 p.m. on a Sunday night: New tattoo? No. New dumb ear piercing? Also no. Cut my own hair? I’m nearly 35 years old. DYE MY OWN HAIR? We found a winner.

I took the train straight to a big box store and bought a box of hair dye, something I swore I would stop doing roughly 10 years ago. The color was probably about two shades darker than my already dark hair. No one in my life will realize I did anything to my hair; the act of transformation was more important than the results. It appears that I did get Yoko’d.