When Vikings defensive coordinator George Edwards's contract ran out after the 2019 season, head coach Mike Zimmer had a job to fill. In an unusual move, he promoted two internal candidates to share the role as co-defensive coordinators. One was 59-year-old Andre Patterson, with 16 years of experience as an NFL defensive line coach and another 21 years in high school and college football as a head coach, defensive coordinator, and assistant coach. The other was Adam Zimmer, Mike’s 36-year-old son, with six years of experience as an NFL position coach and eight years as an NFL assistant.

“No fucking reason [Adam] should be a DC,” a person close to the team told Defector. “Nobody disliked him, but nobody ever thought he would be the coordinator, let’s put it that way.”

No reason, other than the obvious one. “What's the term—nepotism, right?” said one former Vikings player. He said he and his teammates quickly picked up on the reason “Big Zim” had promoted the coach they called “Little Zim.”

“Everybody knows why Adam is there, they all know,” said the person close to the team, who we'll call Source A for clarity.

Patterson had been coaching football since 1982 and coaching in the NFL since 1997, and he’d never been named a defensive coordinator in the league. Patterson’s own son, A.C., is also on the Vikings staff as assistant running backs coach, so he isn’t one to throw stones in a glass stadium, but the former Vikings player described Andre’s promotion alongside the much less experienced Adam as a “slap in the face.”

The Vikings declined to comment on Adam Zimmer's role with the team.

Mike Zimmer calls defensive plays during games but allows Adam to call plays during practice, per two sources, and Adam called the defense during parts of this past preseason too. “It’s some cute shit so he can feel some type of way,” the former player said. Patterson, a powerful speaker, is the one who addresses the defense, and at times, the full team. This past April, Patterson was promoted again, this time adding “assistant head coach” to his co-defensive coordinator and defensive line coach titles. “Probably to make him feel better,” said a second source close to the team, who we'll call Source B.

While not everyone doubts Adam’s abilities—one former player under him told me he’s competent and qualified for the role—his CV pales in comparison to his co-coordinator.

“You have to achieve at such a high level and you look at Andre Patterson, he has performed at a high level every time and he can’t get a sniff, and Adam just had to stick around,” said Source A. “They aren’t even in the same weight class.”

Adam graduated college in 2006 and immediately began his NFL coaching career in New Orleans as a coaching assistant on Sean Payton’s staff (Payton and Mike Zimmer spent three seasons together in Dallas). Adam then went to Kansas City as the assistant linebackers coach for three seasons on Romeo Crennel’s staff. He was arrested on suspicion of DUI when he crashed his car a few hours after the Chiefs lost to the Colts in December 2012. Crennel’s staff was fired following that season, so Adam went right to a job on the Bengals staff as the assistant defensive backs coach, coaching for his dad, then Cincinnati’s defensive coordinator. He hasn’t left his father’s side since.

Adam Zimmer is white and Andre Patterson is black, and this fact hasn’t escaped the notice of their players, or of the people whose job it is to track these things. Every year since 2013, the NFL has commissioned researchers at the University of Central Florida to publish a diversity and inclusion report that examines all NFL coach hiring, with the goal of improving job mobility for minority coaches. The 2016 report had just one sentence about the influence of belonging to a coaching family—it mentioned then-Bills head coach Rex Ryan hiring his twin brother Rob as assistant head coach, a move that backfired. The word “nepotism” was mentioned for the first time in the report in 2017. The March 2020 edition of the report, which mentioned the Zimmers by name, made the longest reference yet to coaches who are related to each other.

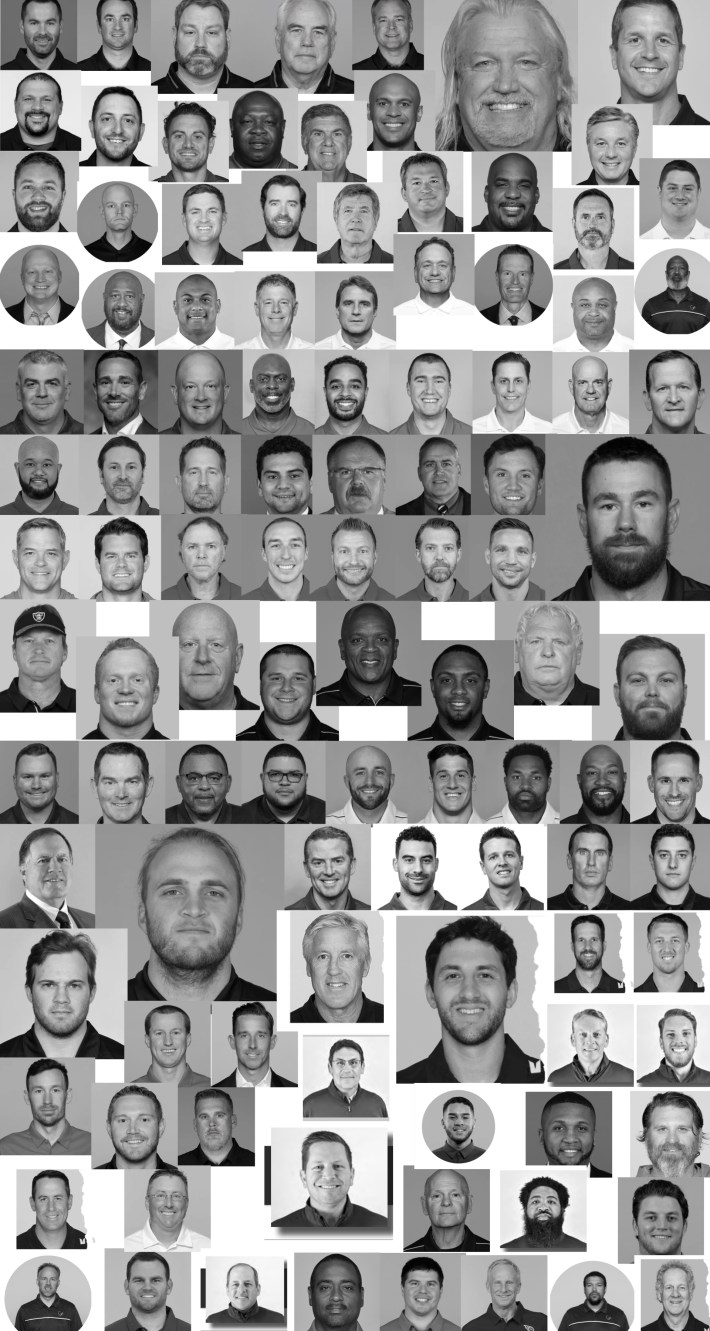

Recent research conducted by the NFL determined that nine of the 32 current head coaches are either the son or father of a current or former NFL coach (including coordinators and position coaches). The same NFL research report also found that 63 total NFL coaches (including coordinators and position coaches) are biologically related or related through marriage—53 of the 63 related coaches are White coaches.

2020 Diversity and Inclusion report

The 46-page report included only five sentences on the topic of related coaches, and the researchers did not bring it up again in the 2021 edition of the report. So in March, after each staff finished its annual firing and hiring cycle, I researched every coach listed on every NFL team website’s coaching staff page, as well as anyone with the title “coaching assistant.”

In most cases, it wasn’t hard to figure out who was related to a current or former coach because most of these official bios proudly list any and all NFL pedigrees. And if the family connection isn't covered sufficiently in the team bio, there are plenty of feel-good local newspaper stories on how cute it is to hire your son. Seattle outlet MyNorthwest.com wrote in 2015 about how Seahawks receivers coach Nate Carroll ended up coaching on his dad Pete's staff: “Younger brother Nate graduated USC five years ago with a degree in Psychology after an illustrious high school career. He wasn’t sure what he wanted to do when his dad offered him a coaching gig in Seattle, unsolicited.”

“We never really talked about it growing up; being a coach," Nate told MyNorthwest. "It wasn’t a focus as a young kid. I mean he’d tell me stuff here and there but it wasn’t until midway through college that I realized [coaching] would be my best opportunity.”

Oh, to be a college graduate landing a NFL job offer without any planning or preparation for the job. (Nate's older brother Brennan left Seattle's staff last year to be the offensive coordinator for the University of Arizona.) The Seahawks did not respond to a request to speak to the Carrolls.

After looking through every team’s coaching staff as of March 2021, I found that Adam and Mike and Nate and Pete are among 111 NFL coaches who are related biologically or through marriage to current or former NFL coaches, out of a total of 792 coaches employed by NFL teams. That’s 14 percent of all coaches. (I hand-counted this total based on my own research parameters: coaches listed on team website and anyone with the coaching assistant title. The NFL’s official coach count is 822: They count all coaching contracts submitted to the league office, which includes all interns who may not be listed on a staff website.) Mike Zimmer and Pete Carroll are two of five head coaches entering this season who oversaw a relative they hired onto their staff. Belichick has sons Steve and Brian as his outside linebackers and safeties coach; Jon Gruden had his son Deuce, whose first NFL job was on uncle Jay Gruden’s Washington staff, as his assistant strength coach in Las Vegas; and Ron Rivera has his nephew Vincent on staff as a defensive quality control coach.

Vegas led the league in father-son combos on the same staff this season, with four: the Grudens, the Cables, the Smiths, and the Miluses. Las Vegas also leads the league with nine coaches related to a current or former coach on staff, followed by Denver and New England with eight, and the Washington Football Team, whose head coach, offensive coordinator and defensive coordinator are related to a current or former NFL coach. The Steelers are the only NFL team without a single coach listed who is related to a current or former NFL coach, though general manager Kevin Colbert has his son on staff, and Dan Rooney Jr. is the team’s player personnel coordinator.

Overall, the league averages 3.4 coaches per team who are related to a current or former NFL coach, and the percentage of coaches at the supervisory levels—the ones with hiring power—is even higher. Eleven of 32 head coaches are related to a current or former NFL coach. There are 24 coordinators who are related to current or former coaches, almost a full quarter of them.

“Loyalty is a big part of it,” said former NFL head coach Wade Phillips, whose dad Bum hired him in New Orleans for his first NFL job. Wade also hired his own son, Wes, to his first NFL job, when he was head coach of the Cowboys. “You can help teach your son or family member the things you want them to do and so, sometimes the most important thing is hey, get somebody that is going to work hard and listen to what you say and do what you want to get done and that’s what your kids have done their whole lives, whether it is coaching football or being your son.”

Nepotism isn’t exclusively for white people (as several white people interviewed for this story were quick to point out to me), but the percentage of family hires is overwhelmingly white: 78.3 percent. Coaching is overwhelmingly white, of course—75 percent of all NFL coaches are white, according to the league’s 2021 data—but how does a majority stay the majority? Hiring blood relatives certainly helps.

Buccaneers head coach Bruce Arians has spoken extensively about the importance of having different voices on a coaching staff. His staff in Tampa has four black coordinators, two women assistant coaches, and one coach who is related to a current or former coach (defensive/special teams assistant Cody Grimm). I asked Arians at a midweek press conference this season about whether he’d thought critically about the number of coaches who are related to other coaches around the league and if that is a hurdle to increasing diversity.

"I think those guys who grew up in the business, they fall in love with it early or they don't,” Arians said. “If you work at a place where you don't have a nepotism policy [against hiring relatives], yeah, it's fun to have your son on your staff. I would love to have my daughter on my staff. But a couple places I worked, that wasn't possible."

In 2013, when he got his first NFL head coaching gig in Arizona, Arians wanted to hire his son Jake as a special teams coach, but the Cardinals have a policy that prevents that type of nepotism hiring. (The Cardinals confirmed they have a nepotism policy that extends to all positions in the organization, but didn’t provide specific details of the policy). Arians said he wasn’t sure if the Buccaneers had such a policy in place; the Buccaneers told Defector they do not discuss hiring policies publicly.

I reached out to all 32 NFL teams to ask if they had a nepotism hiring policy in place to prevent coaches or general managers from hiring their own relatives onto their staff, or at least police it. Eleven teams declined to comment, saying that they don’t publicly discuss internal policies; the Chargers, Broncos, and Browns said they do not have a policy; and just two clubs, the Cardinals and Falcons, said they do have a nepotism policy. The remaining 16 teams did not respond.

(The Falcons have one father-son combo on their coaching staff: defensive coordinator Dean Pees and his son Matt, who is a defensive assistant. The Falcons told Defector that the rule across the Blank Family of Businesses is that relatives are not to work in the same department unless approved by Human Resources. The Falcons noted that all assistant coaches report to the head coach, not to the coordinator, meaning Matt doesn't report directly to Dean.)

“Where do I get to highlight the irony of [Cardinals owner] Michael Bidwill having a no-nepotism policy?” asked one team executive whose club does not have a nepotism policy. “These teams are all inherited, you have to start with that premise. These are family businesses. So I find it disingenuous that family businesses would say, ‘Look, you can’t hire family members.’”

That family business dynamic makes this a “third-rail” topic, the executive said. Who can point a finger when everybody is doing it?

I requested to speak to every current head coach with a relative on his staff, and each team either denied the request or ignored it. I also had no success when I requested through teams to speak to the third-generation coaches in the NFL. Mike Shanahan didn’t return my call or text. ESPN denied my request to talk to Rex Ryan, who is both the son of a former coach and the father and brother of a current coach. I requested to speak to three different owners, with the same results.

In the 2020 and 2021 diversity and inclusion reports, Troy Vincent, the league’s EVP of football operations, wrote, “Merit-based policies and practices need to be considered in order to discourage the system of nepotism that unduly influences the hiring cycle—family, agents, friend networks.”

Vincent said that for the last two years he’s included numbers on related coaches, what he terms “legacy hiring,” in the presentation he and his staff give to a group of coaches, general managers, league personnel, academic professors and consultants at the annual NFL scouting combine. “It frankly came out of really evaluating, what are barriers to entry?” he told me. “That jumped out at me. … It really became, it’s not what you know or what you are capable of, it’s who you know.”

Vincent said coaches around the league have brought up the issue of pervasive nepotism hiring with him, often not in so many words. “They go, ‘Man, you know what it is here,’” he said. “So you leave it at that. That's enough to go, ‘OK, I got it.’”

Vincent said he has not yet planned out what a “merit-based” policy might look like for NFL hiring, but it’s the next step towards his goal of “reimagining” the NFL hiring process. He took notes during a Zoom interview with Defector, and seemed surprised that some clubs already had nepotism policies in place. He said he plans to follow up with all 32 teams to find out which clubs do and do not, and encourage them to adopt what the Falcons and Cardinals have done. “Everyone should know that there is an opening,” he said. “Everyone should see the job description. Everyone should have a fair and equal opportunity. Male, female, Caucasian, person of color, to say, ‘I would like to apply for that position.’”

Rod Graves, director of the Fritz Pollard Alliance, a group that promotes minority hiring in the NFL, has had many conversations with owners about improving minority hiring. But he said he’s never discussed with them this form of nepotism. After reviewing my spreadsheet of related coaches, he said, “I recognize this as a potential issue, but today I don't see it as one that I think we can necessarily say, this is a problem.”

Graves, who is black, said that he believes coaches who share the same agent are a more pressing barrier to minority hiring than coaches who are related to each other. (Eleven different NFL teams have more than one supervisory coach or general manager represented by the same agent.) Graves was the Cardinals' general manager for 10 years, and he said that his dad, Jackie Graves, a longtime NFL scout and personnel director for the Eagles, helped him get his first NFL job in the Bears’ scouting department.

“It is certainly not objectionable for people in your family to have interest in being in the business,” he said. “The only time that I would recognize a potential issue, as far as the Fritz Pollard Alliance is concerned, is when those family members have taken a position away from someone who is more qualified to do the job.”

Graves said he thinks it’s OK for head coaches to hire their own relatives as long as the relative is in a learning role, with the head coach or another supervisor teaching them and “covering” them. He wouldn’t name any specific examples of a head coach getting this wrong, but said that in order for him to be aware of a problem, someone on the staff would need to complain and report it to him. No one has.

Hue Jackson, former Browns head coach and one of 19 black non-interim head coaches in the NFL history, according to the league's internal data, said he’s been thinking about this topic for some time. “You see so many sons coming into the game and being thrust into positions,” Jackson said. “They get to hit the ground running … I have had coaches come to me feeling upset, because they don't feel like they can get to where they want to go.”

Jackson has never hired a relative, but has hired father-son combos to his staff. After the 2016 season, Jackson’s defensive coordinator Gregg Williams said his son, Blake Williams, the Browns’ linebackers coach, was “the best young coach I’ve ever had.”

"We won't keep him very long,'' Williams told Cleveland.com. "He's going to be a head coach or a coordinator in a hurry when we do what we need to do at Cleveland 'cause people are going to recognize that. They're going to recognize it's not just me.”

They did not do what they needed to in Cleveland. Blake followed Gregg to the Jets, this time as a defensive assistant whom head coach Adam Gase originally didn’t want to hire. Gregg was fired in New York during the 2020 season, Blake was fired after that season, and the two remain out of the league.

Jackson said he thought Blake was a great coach, and he hired him because he wanted to give Gregg the defensive staff he wanted. “When you are hiring coaches and especially ones in leadership positions, the one thing you want them to be is comfortable with the people who they have on their staff, because that is when they are at their best,” Jackson said. “If it's a son I want to make sure the guy is qualified. I am not going to hand somebody a job because they are somebody's son.”

That type of thinking is common throughout the league. A few teams, like the Jets, have more ownership involvement in the hiring process, and others are structured to run coach hiring through the general manager, but many clubs allow the head coach almost full autonomy to decide who he wants on his staff.

The Rooney Rule requires teams to interview two external minority candidates for head coach and coordinator openings, but there aren’t any rules that apply to hiring position coaches or assistants.

“Head coaches should pick their own staff. I fundamentally believe that,” said the executive from a team without a nepotism policy. “I find some of the typical HR policies don’t meld well with football, and then you wind up adopting certain ones and not others. If you brought the head of a Fortune 500 company’s HR department to an NFL building, you could never explain hiring and firing coaches. ‘OK, we are going to fire all 20 people in this department and replace them with people we have never met.’”

Every coaching staff has several semi-entry-level gruntwork positions, often called quality control coaches. “Here's what happens,” the team executive said. “A coordinator says, ‘OK, well I'll come but I want my QC to be my son.’ If you're the head coach, you're like, ‘OK, I have to go hire a QC anyways, so why not?’”

But these QC jobs aren’t meaningless busywork jobs; they're a foot in the door. Those jobs lead to assistant position coach jobs, which lead to position coach jobs, which lead to coordinator jobs.

Both Belichick sons went straight from college to jobs on their dad’s staff, Steve as a coaching assistant and Brian as a scouting assistant. They did not coach high school or college football, and they are both now NFL position coaches. Brian played lacrosse at Trinity College, and Steve played lacrosse at Rutgers. According to his Patriots bio (which carries no mention of Bill, by the way), Steve did do a little bit of work to get ready for his NFL future: “After playing four years of lacrosse at Rutgers, Belichick walked on to the football team as a long snapper to help in preparations for a career in coaching.”

“Just read their bio, that’s all you need,” said one person close to the Patriots. “Remove the name and tell me what you have. Seriously.”

Gary Kubiak, who has twice been a head coach, said that he would interview multiple candidates for those lower-level jobs on his staff. “I had files and files and files of coaches,” he told me. “I would bring in multiple people and that’s how people grow, through interviews, give them the chance to interview not only in front of me but the coordinator. “

Gary’s son Klint is now the Vikings’ offensive coordinator. They first worked together in 2016 when Gary hired Klint, who was then the receivers coach at Kansas, as an offensive assistant for the Denver Broncos. Gary said when Klint told him he wanted to get into coaching, he told him to go get his master’s degree as a graduate assistant for a college team to show he was serious about it. I asked Gary if Klint went through the standard hiring process and interviewed against other candidates. “I can’t tell you right now, who, how many guys we brought in, or this or that, I don't remember all that right now,” he said. “I told you he had some excellent opportunities in college football, and when I was looking for a QC coach on the offensive side of the ball, I thought he would be a tremendous asset to what we were doing.”

When Gary retired from a 29-year NFL coaching career after the 2020 season, the Vikings promoted Klint to his dad’s job. The team also interviewed Tyke Tolbert, wide receivers coach for the New York Giants, presumably to satisfy the Rooney Rule which at the time required teams to interview at least one external minority candidate for head coach and coordinator openings (it has since been updated to require two external candidate interviews). But the job was Klint’s, and probably had been for some time.

Gary joined the Vikings staff as an assistant head coach and senior offensive advisor in 2019, the same year Klint was hired as the Vikings’ QBs coach. At that point, Gary had been out of coaching for two years; health issues forced him to resign from the Broncos' head coaching job after the 2016 season. In 2020, Gary’s lone season as Vikings OC, he worked closely with Klint to get him up to speed on the OC job, Source B told Defector.

“Sometimes you see guys that stay too long because they want to set their kid up,” Source A told me. “I think Kubes did that for Klint, get him set up before he walked out the door, even though his health said no.”

This is the advantage that Klint has over his peers (well, except for the 63 other NFL coaches who are sons of current or former NFL coaches, including his brother Klay Kubiak, defensive quality control coach for the Niners. Another brother, Klein Kubiak, is a scout for the Cowboys). Gary told me he prepared Klint just as he would any other coach on his staff. “You are trying to prepare all of them to be coordinators and head coaches,” he said. “That year, he is coaching QBs, and I am the OC, so that is as close a fit, that is the fit that is all over the game, a QB coach and an OC, as far as what he was doing and what I was asking him to do.”

Gary said Zimmer and general manager Rick Spielman didn’t personally ask him about Klint in the process of promoting him. “They made a decision three or four months later to make Klint the coordinator,” he said. “So I don’t know, you would have to ask them how they came to that conclusion.”

These days, Gary is retired and living on his ranch in Texas. He’s not listed on the Vikings coaching staff, but Source B told me, “He is still involved.” When asked about his level of involvement, Gary insisted he’s not at all. “I let Klint and them do their own business.” The Vikings declined comment on Gary Kubiak's involvement with the team.

Former Washington Football Team and Chargers head coach Norv Turner told me he and his son Scott “fought the urge” to work together right away because he felt it was valuable for Scott to learn from other people. After Scott had eight years of coaching experience under his belt in high school, college, and the NFL, he and his dad joined Rob Chudzinski’s staff on the Cleveland Browns in 2013. Norv was the offensive coordinator that season, and Scott was the wide receivers coach. The following season, after the whole staff was fired, Mike Zimmer hired Norv and Scott onto his first Vikings staff. Norv was again the offensive coordinator and this time, Scott moved up to quarterbacks coach, the position that functions as the primary pipeline to offensive coordinator. (The league’s 2021 diversity and inclusion report said that 24 of 31 current offensive coordinators [as of March] have experience as NFL QB coaches, and 70 of the 72 quarterbacks coaches who earned offensive coordinator opportunities from 2002 to 2020 were white.)

Norv said Zimmer didn’t know Scott personally, but was sold on the fact that Scott had been in Cleveland with Norv running the same offense. “I explained to Coach Zimmer that having a guy there that had been involved in the offense was important and he, along with me, could help the other coaches learn the offense,” Norv said.

Norv unexpectedly resigned from his position in 2016 and the Vikings fired Scott after the season, so after a year in college football, Scott followed his dad again, this time back to the Carolina Panthers, where he’d started his NFL career. Norv was the offensive coordinator on Ron Rivera’s staff, and Scott took the quarterbacks job again. Scott is now the offensive coordinator for Rivera’s Washington Football Team.

I asked Norv if he’d ever considered whether coaches hiring their family members was a barrier to increasing diversity in the NFL. He didn’t really answer the question, but at the end of the interview I asked if he had anything else he wanted to say. “Everyone wants the league to be more diversified, and more guys to get more opportunities,” he said. “I worked with some great coaches that deserved opportunities and could be a coordinator or be a head coach. I worked with Fritz Shurmur at the Rams, and he went on to be the DC at Green Bay when they won the Super Bowl and appeared in another Super Bowl and he came close to getting head coaching jobs a couple times, and he would have been a great head coach in my mind and never got the opportunity. Unfortunately that’s the case for a lot of guys.”

Fritz Shurmur, who died in 1999, was white. His nephew, Pat Shurmur, is a two-time NFL head coach and currently the Broncos’ offensive coordinator.

One former NFL assistant coach interviewed for this story said he left to take a college job because he was frustrated with the lack of mobility. “I didn’t want to leave the league, but I had to,” he said. This coach is a member of a minority group, and he isn’t related to any other current or former NFL coaches.

When this coach got his first NFL job, he said the wife of another coach introduced herself to him and his wife, and asked, "So, how did you guys get this job?"

“Instead of saying, What did you do? Where did you come from? It was, How did you get here? Who did you know?” the coach said. “It’s true, you have to have an in, and the biggest in is, fuck, ‘I have been looking at this person every day their whole fucking life.’ That shit helps, right?”

The former Vikings player told me he’s interested in getting into coaching someday, but he feels jaded by the whole process. “For me, my whole dream is fixed to the NFL and then you get in and know the ins and outs and you're like ‘All right, I see what's going on here, I'm going to get my checks and then let me get out of here.’ … Do I want to sell my soul and become a football coach and deal with all the fucking—knowing what I know now from being in the league, it’s all a gentlemen’s club.”

One young NFL assistant coach described his experience as a minority without any family connections in the NFL as a “double whammy.” He’s been discouraged by the obvious nepotism hiring on the team that he works for. “You're just sitting there like, ‘What am I really doing? What am I working hard for?’” he said. “If I don't have a last name that is recognizable, then it's kind of for nothing.”

This reality sank in for this assistant coach when the Rams hired Sean McVay at 30 years old, becoming the youngest-ever NFL head coach. “I was like, damn! This kid must be exceptional,” the coach said. “Then I was reading a book and I saw the name McVay, and I was like, wait a second! His fucking grandfather [former Giants head coach and longtime NFL executive John McVay] was a big-time dude! It all makes sense, so you're almost asking yourself why you do it. And you hope that one day it's going to change, but you kind of don't know. It's really entrenched.”