I have heard John Sterling's voice more than anyone's in the world outside of (maybe) my parents. Three hours a day, most days from April through October, every year since I became a baseball fan. That constancy gets to a fan, worms inside their head to the point where they can no longer be objective about it. It's a comfort sound. Sterling's is the voice of my springs, as sure a sign as any groundhog or crocus that warmth is on the way. The voice of my summers, a droning baritone background through the dog days. The voice of my autumns, the final word of heartbreak that will send you off into the long cold, or of jubilation that feels like the end of a shared journey. Many of the happiest moments of my life, John Sterling told me about first.

And now, almost inconceivably to me, he is retiring. Retire? How can he retire? How can they have the Yankees without John Sterling? That's a silly thing to think. There were Yankees games before Sterling and there will be after. But I have to take that on faith. I have never known the Yankees without him.

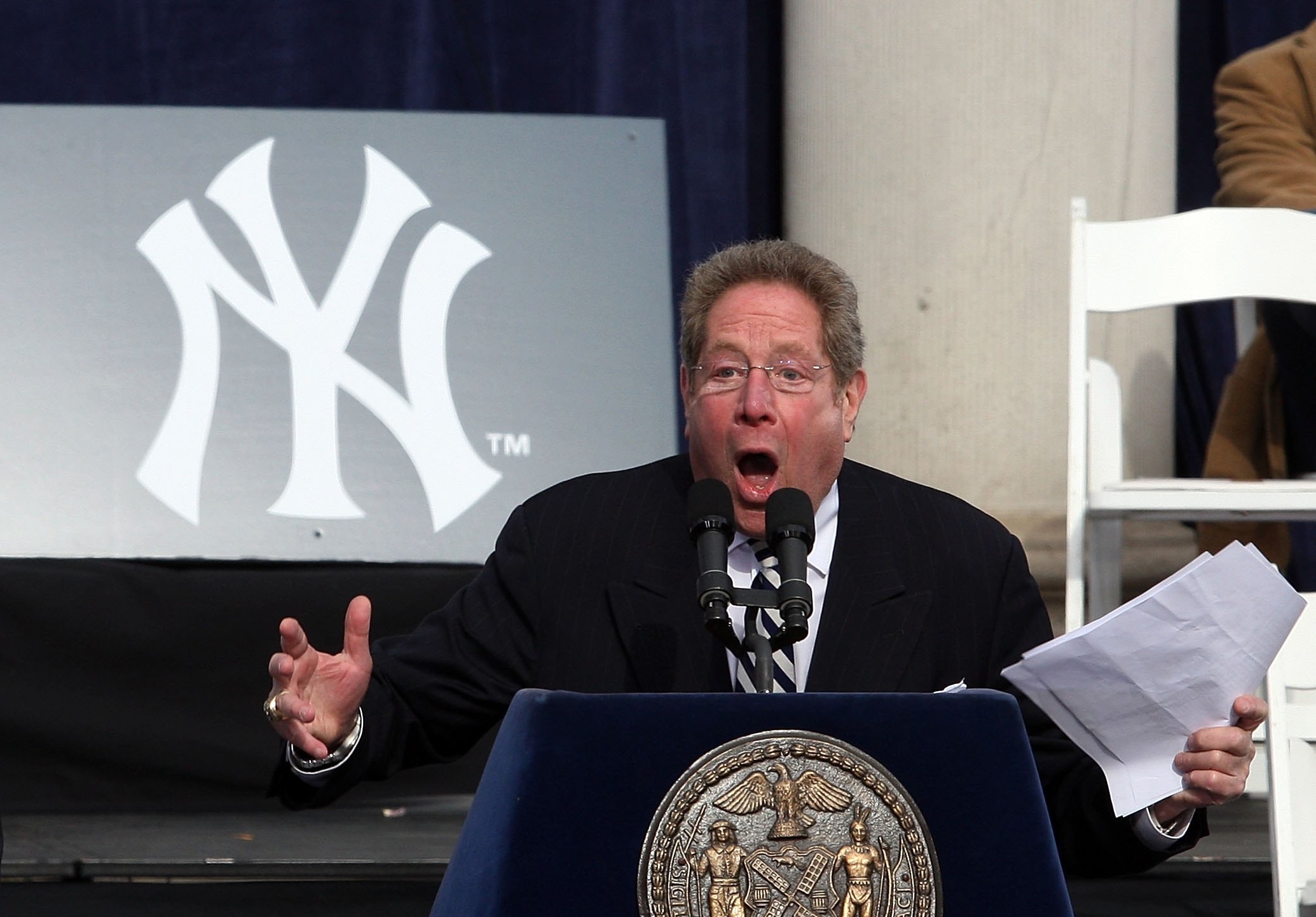

Sterling's pro sports broadcast career lasted more than 50 years, and included teams both unlikely and defunct: the Atlanta Hawks and Braves, the Baltimore Bullets, the New York Raiders, the New York Stars, the Nets, the Islanders. The life of a broadcaster is ever peripatetic, especially in the early going. But it was the Yankees that would last. Sterling called 5,631 Yankees games, including more than 200 playoff games and five World Series championships, between 1989 and his sudden retirement announcement Monday, effective immediately. He says it's not a health issue, that he's 85 years old and has been thinking about it for a long time and wishes he had done it this winter, but better late than never. If this moment was inevitable in his mind, I always sort of pictured him keeling over at the microphone, perhaps his heart giving out during some particularly melodramatic victory.

I first started paying real attention to baseball in 1992, Sterling's fourth year calling the team (and his first paired with Michael Kay, a partnership that would last a fruitful decade that felt to a young fan with no frame of reference like a permanent thing, and like a shocking breach of stability when it dissolved; to put things in perspective, he has nearly doubled the length of that run alongside Suzyn Waldman). I liked the way he said the names: Velarde, Stankiewicz, Kamieniecki, Monteleone. I did not really understand yet how bad the team was, and had been. But I sensed Sterling's growing excitement as a new crop of players came up and began to excel. He told me of the entire careers of Derek Jeter, Jorge Posada, Mariano Rivera et. al. as bedtime stories, three hours a night. When the Yankees—who by that time I had become mad about—finally won it all, our television was muted and the radio turned up, so we could hear the end of the last game the same way we'd heard the others.

Stick around doing the same thing long enough and you risk falling into caricature. Sterling never saw that as a bad thing—he leaned into it. "My act," he called it. The inveterate showtunes guy got it; he was performing, entertaining an audience. And they wanted him to play the hits. They wanted the personalized home run calls for every single player who put on the pinstripes. It was a bit of silliness in a moment of triumph, and if it gradually veered from fun to cheesy, he committed to the bit so fully that it came back around to fun. I will never hear Bernie Williams's name without hearing "Bern, baby, Bern," or Kyle Higashioka's without thinking of him as "the home run stroka," or, no matter how much I'd like to, Nick Swisher's without my brain yelling "Swishalicious!" He'd find any excuse to sing a few Broadway bars, and knew the power of a catchphrase. "It is high, it is far, it is gone"—yep, that's what a home run is, all right. "The Yankees win"—you wouldn't think such a brief statement of fact could be a slogan, until Sterling discovered you could extend the "the." You could always tell how genuinely excited he was or wasn't about a game from the length of that "the" and the intonation of "win."

If Sterling lost a step or three in his later years—there were a number of "home runs" that failed to leave the ballpark—that's the nature of a career, athlete or broadcaster. You remember the primes and you coast off those good feelings even through the decline, until they realize usually a little too late that they can't or don't want to do it anymore. Growing up means saying goodbye. "I’ve been on the air since Feb. 1, 1960 and I’m tired," Sterling said yesterday.

I was tired too, in one of those crystal-clear yet nonspecifically dated John Sterling memories of my childhood. A West Coast game, late. My clock radio blinking red in the darkness. School tomorrow; I didn't want to go, so I didn't want to fall asleep. In bed, under my covers, listening to the radio turned low enough so my parents wouldn't hear. Trying to stay awake. Sterling keeping me company.

Another one: On the fire escape. No air conditioning, one of those Manhattan summer nights so humid the air feels like split-pea soup: it has a weight. It's only marginally better outside—no breeze whatsoever—but it is better. Portable radio brought out. Game on. Sterling keeping me company.

This, I think, is what a good announcer does, especially in baseball. They are a companion more steadfast than any friend—through the highs and the lows, always there. They are the narration of your joys and hopes and disappointments. They are your entry point into fandom, and the sound of your best memories. And memories can't retire.

"Nothing will ever be the same. It can't be," said Waldman yesterday. "Life goes on and we all go on but nothing else will be the same.”

That's baseball, Suzyn.