Within the storied canon of lesbian period romances between the two different types of women—blonde and brunette, both white—Desert Hearts is my favorite of the genre. The premise is as sleek as its approximately 90-minute runtime. Vivian (Helen Shaver), a buttoned-up English professor at Columbia, moves to Reno, Nevada, also known as the divorce capital of the world, to stay the six weeks required to get a quick, no-fault divorce. Enter Cay (Patricia Charbonneau), a younger, free-spirited (read: lesbian) woman, who pursues Vivian about as openly as a queer woman could in 1959. Tumbleweeds roll, nipples touch, and soon Vivian's world unravels.

Vivian first encounters Cay on the road to Reno, in the passenger seat of a car driven by a woman named Frances, who owns the all-inclusive divorce ranch where Vivian intends to spend the next six weeks reading and writing presumably stodgy literature. After Frances and Vivian's sensible car passes Cay, who is driving a glimmering convertible in the opposite direction, Cay reverses the convertible to say "hi" and start laying it on thick: "Can I call you professor?" she teases, dark hair whipping in the wind. When an oncoming car emerges behind her, Cay waits until the absolute last second to shift her car into drive and avoid a crash.

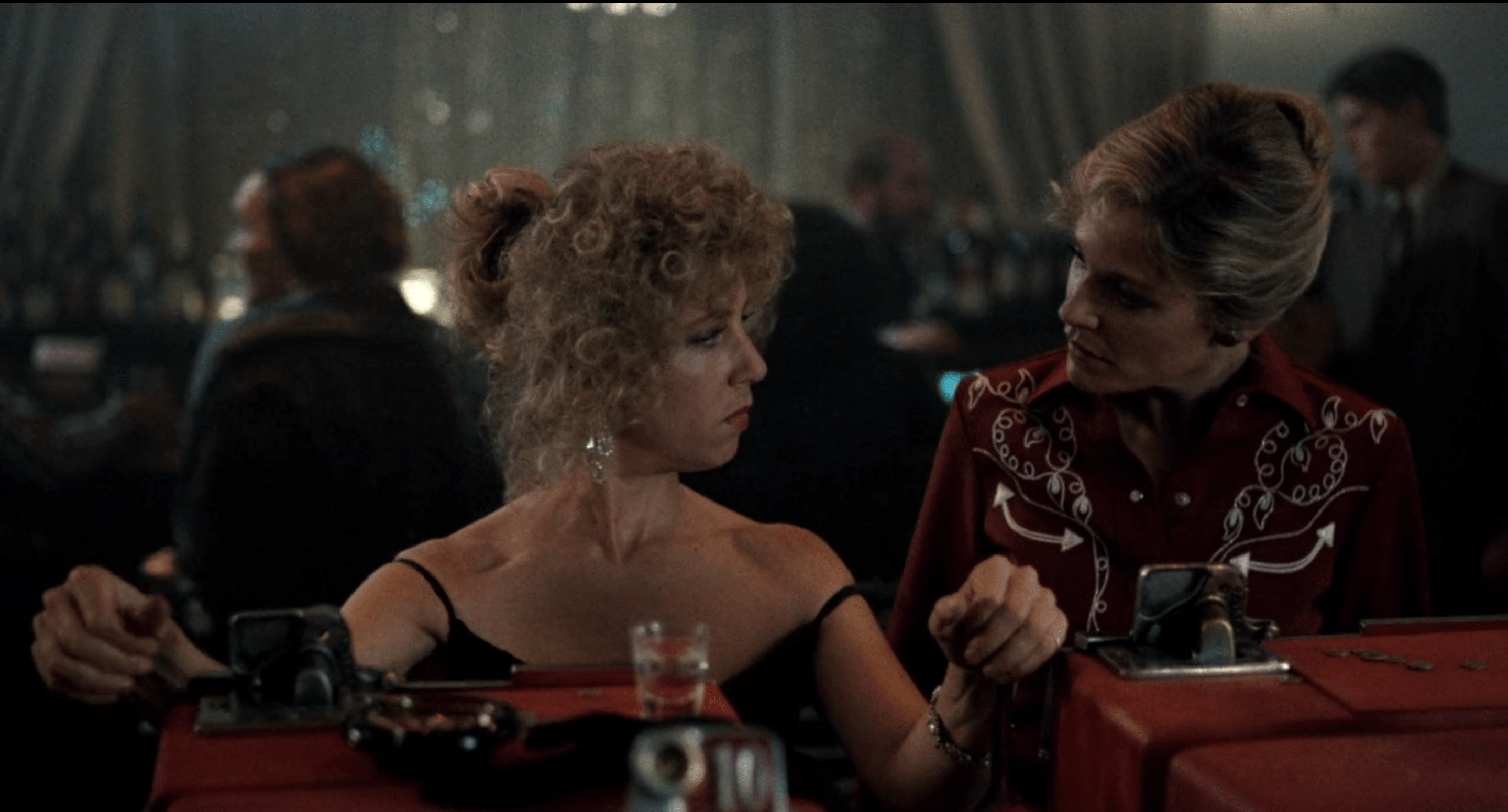

The meet-cute establishes Vivian and Cay as a familiar pair of opposites: the conservative, sexually repressed older woman with all her buttons buttoned up and the free-wheeling lesbian potter in jorts. To Vivian, Cay embodies a tantalizing and thoroughly unconsidered way of life, one that certainly exists less than a mile away from Vivian's home in New York City but that Vivian has never before seen, or chosen to ignore. Falling in love is always a risk, but falling for Cay, as far as Vivian sees it, would be to risk it all: her reputation in society and her understanding of herself, not to mention her cushy room at the divorce ranch. The movie underscores this with scenes from Cay's day job as a change girl at a local casino, where the air is hazed with smoke and thick with the sounds of the slots, where the women are glum and the men are lecherous.

Desert Hearts was adapted from Jane Rule's 1964 book, Desert of the Heart, which Rule wrote after working in a casino one summer in Reno. The movie is simpler and more sentimental than the novel, softening the age gap from 15 years to a less objectionable decade. (In the novel, the two women resemble each other. And not only are they often mistaken for mother and daughter, but Vivian's character is struck with post-coital, maternal feelings toward her young lover.) Rule, a 6-foot-tall American-born Canadian, wrote Desert of the Heart in 1961 and was rejected by 22 publishers before the book finally came out in 1964, five years before Canada decriminalized homosexuality. At that time, Rule's novel was one of the first novels to take lesbian desire seriously and offer them a hopeful ending, much to the dismay of critics.

Director Donna Deitch first learned about Rule's book in 1979, when a friend gave her a copy. She proceeded to read it seven times in a row and knew immediately she wanted to adapt it for film. "I instantly liked the central idea: a love affair between two women set in the context of all the gambling and risk-taking going on in Reno," Deitch said in an interview in the Monthly Film Bulletin published in August 1986. "It was a book where you were rooting for them to be together, not waiting for one or another of them to kill themselves." Deitch was alluding to other films in the limited lesbian canon of the time, in which queer women went out one of two ways: either ending up with a male love interest or dying suddenly. The oeuvre included The Children's Hour (1961), in which a woman who has fallen for another woman hangs herself; The Fox (1967), in which two women consummate their relationship only for one of them to be crushed by a tree; or Personal Best (1982), in which a queer track-and-field star leaves her lesbian lover for a man.

Within this context, the risks in Desert Hearts are cozy by comparison. The movie is honest about the threats that follow queer women in its world—they are harassed by men behind closed doors and abandoned by family—but nothing veers even close to such rancid fates as death and compulsory heterosexuality. The West Coast is more than its earthquakes, but Desert Hearts' hopeful ending was seismic for its day and age.

In the 1980s, as the AIDS crisis climbed toward its peak and homophobia was a matter of routine, no one wanted to fund Deitch's swoony lesbian movie. She spent nearly six years fundraising, cobbling together an NEA grant and individual donations to cover the film's $1.5 million budget. She even sold her house to pay for the soundtrack, a dreamy assemblage of Patsy Cline, Kitty Wells, and other country crooners that waft through the movie, beat by beat. What's riskier than selling your house so that 28 seconds of Elvis can play in a brief cutaway scene of Vivian undergoing a beloved queer ritual (buying her first button-down)?

I first watched Desert Hearts in the summer of 2020, and, in unknowing homage to Deitch, I watched the film on repeat that first week. I am not old enough, either in body or sexuality, to have grown up in a world where the only representations of lesbians onscreen were murderous, suicidal, or dead. (My initial canon had its own problems, overstuffed with white, frequently morose lesbians who existed in any time but the present day.) By comparison, the comfort of Desert Hearts felt intoxicating. The acting can be rough around the edges, and the script is occasionally, charmingly hokey. But if you allow yourself to fall, as I did, it all comes together in a feverish romance.

Deitch understood that the stakes of lesbian yearning are more than sufficient to power a feature film. Time in Desert Hearts is languorous and unstructured, offering a fantasy outside late capitalism in which yearning can provide the structure to your days. There is little else to do in the desert but exist in your body and succumb to your desires; the pandemic proved that enough free time will crack even the most oblivious egg. Each of Desert Hearts' gauzy fades unveils a dykier Vivian. She trades her weird, prim cap for a cowboy hat. She swaps her pencil skirt for pants. She buys her button-down and, after some half-hearted demurring, eventually has a big, gay orgasm.

Critics sometimes frame the climax of Desert Hearts as its sex scene: a breathy, almost unbearably quiet montage of consummation after days and days of honky-tonk yearning. And sure, the explicit nature of the scene was radical for its day. But for me, the true heart of Desert Hearts takes place in the wee hours of the morning after the women attend the engagement party of Cay's best friend and sometimes lover, Silver. Cay drives a tipsy Vivian along the pitch black of a desert road to watch dawn unfurl at Pyramid Lake and paint the mountains peony. The two stroll along the mirrored periwinkle water before getting caught in a rainstorm, culminating in a sopping, unreserved kiss through a car window. This quenching moment—after a stretch of dusty, arid desert days, where everything, plant and animal, thirsts for water and scalds under the sun, where survival itself feels improbable, let alone actually living—is one of the best moments of catharsis in any romance movie.

At some point in the novel, Cay's character shares a philosophy with her older lover: "If you don't play, you can't lose." She's referring to gambling, with the wisdom that can only come from working at a casino and watching patrons lose it all, again and again and again. In the film, Deitch revises this line to be more hopeful, and even delivers it in a brief cameo by the slots: "If you don’t play, you can’t win." In the world of Desert Hearts, this is the bigger risk: Losing one's reputation is surely a smaller gamble than walking away from a great love. With these outcomes in mind, the only option is to cross your fingers and play your hand. I imagine this revision could only have come by porting over Rule's lesbian world into the future and daring to imagine more for her characters. It is impossible to know what an adaptation of Desert Hearts in the 1960s would have looked like, but it would almost certainly be less hopeful.

Although Desert Hearts is often called the first lesbian movie with a happy ending, it's not clear if Cay and Vivian stay together in the end. As Vivian takes the train out of Reno, she coaxes Cay to join her, if not all the way to New York City, then at least to the next station: "What is it you want?" Cay asks in those last moments. "Another 40 minutes with you," Vivian answers. But a happy ending doesn't have to last forever; some little loves never leave the dance floor. Any person of dyke experience will tell you that we are rarely fated for the first woman we fall in love with, but that she will always hold a space in our heart for being the first to crack open our world. I will never forget how that moment shimmered for me. I walked into a party in her living room. We locked eyes and began to dance. If you had told me that she would break my heart later that summer (she did), I wouldn't even have cared. All I could think about was the next 40 minutes with her.