One way I like to feel small is thinking about the fundamental, hilarious incompatibility of human and geologic timescales. On a geologic timeline, India is charging into Eurasia like a phalanx, deforming the continent and sending the Himalayas vaulting to the heavens, though in the handful of decades you and I will be alive on this Earth, the mountain range may only grow by centimeters, or even shrink if the earthquake cycles get weird. Los Angeles and San Francisco, roughly 400 miles apart, will be next to each other in another 20 million years. Our planet's crinkling skin is in constant motion and it offers us precious few examples to feel it in a way our tiny brains can grasp. Iceland, currently preparing for a seemingly inevitable volcanic eruption of unknown size, is one such example.

If you look at a map of the tectonic plates (or even the outlines of the west coast of Africa and the east coast of South America), you will notice that the Atlantic is currently expanding down its center. You can see it on satellite photos, looking like a zipper running broadly north-south. Iceland sits astride this rupture, and not by chance: The island is the result of some magmatic upwelling along the spreading center. As land goes, it's extremely young, constantly being renewed by fresh plugs of lava from somewhere in the deep Earth (there's no scientific consensus on how deep). It is being slowly torn apart by the divergent motion of the Eurasian and North American plates, with fresh magma rising from either the mantle or crust to fill the gap.

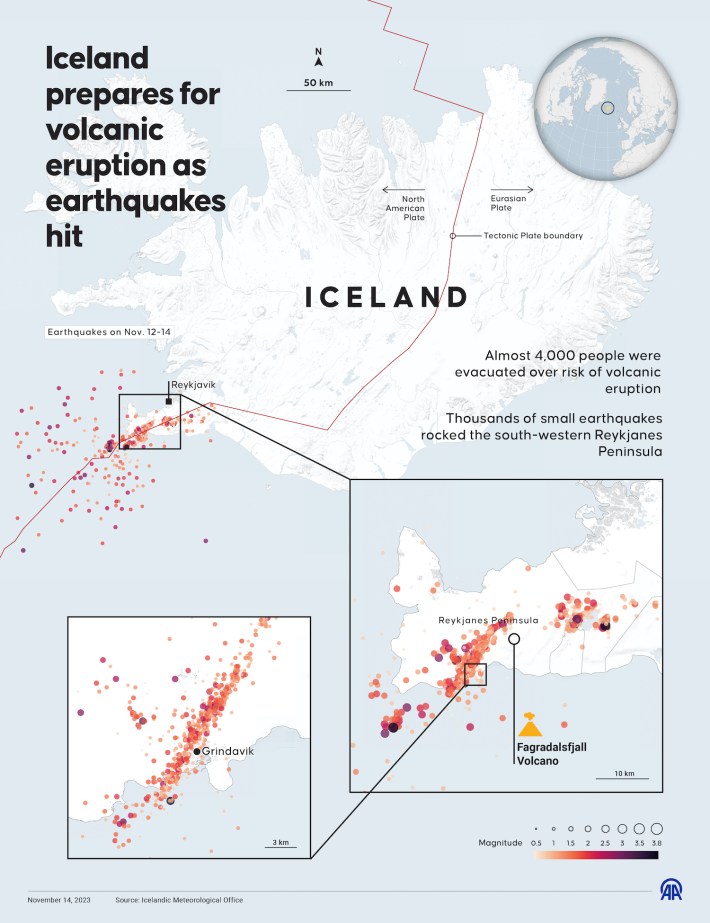

I think that's a useful framing device for this week's news. Iceland's volcanism is neither novel nor unpredictable; it's a fundamental condition for the island's existence. In the past three weeks, officials have reported a significant uptick in seismic activity (hundreds of shakes on Tuesday alone) below the Reykjanes Peninsula, rumblings indicating that a 10-mile-long magmatic intrusion called a dike is making its way to the surface some 25 miles southwest of Reykjavík. Iceland’s Meteorological Office issued a warning on Monday, saying there was a "significant likelihood of a volcanic eruption in the coming days."

Those who live in the Bay Area or Japan will note here that earthquake monitoring is a tricky science, and that early warnings of the massive quakes endemic to those regions are essentially impossible to predict on actionable timelines. Iceland is different, since there's a long-established pattern with a series of telltale signs. The regional volcanism produces huge eruptions, like Eyjafjallajökull in 2010 or Fagradalsfjall in 2021, with the latter indicating the possible resumption of a regular 800-year cycle of eruptive activity. Local towns have been evacuated, the famous Blue Lagoon pools have been closed, and the government has begun building emergency 25-foot lava barriers around a nearby power plant. The ground in the area has risen by three or so feet, and it's starting to crack apart like a pavlova.

The magma could erupt within days or weeks, though if it doesn't pop out within a month or so, it likely won't happen for a while, as the magma will cool and settle. Remember, this isn't lava being spewed up out of the Earth. "These sorts of dikes are actually a tectonic, not a magmatic feature. In other words, the lava is filling a fracture, not forcing its way into the rock," Icelandic scientist Edward Marshall told LiveScience. It is remarkable how predictable and how quick all of this volcanism is, which makes it an instructive and rare window into how the Earth is constantly, violently pulling itself apart and stitching itself up. My brain is not powerful enough to grapple with the heft of geologic time, but I can understand the ripping apart of a chunk of crud, and that gives me a small window into the vast scope of the planet's churning. Alternatively, other weird volcanic activity, like the new island that just formed off the coast of Japan, could mean that the dwarven gods who control the Earth's mantle are getting in the lab and trying stuff.