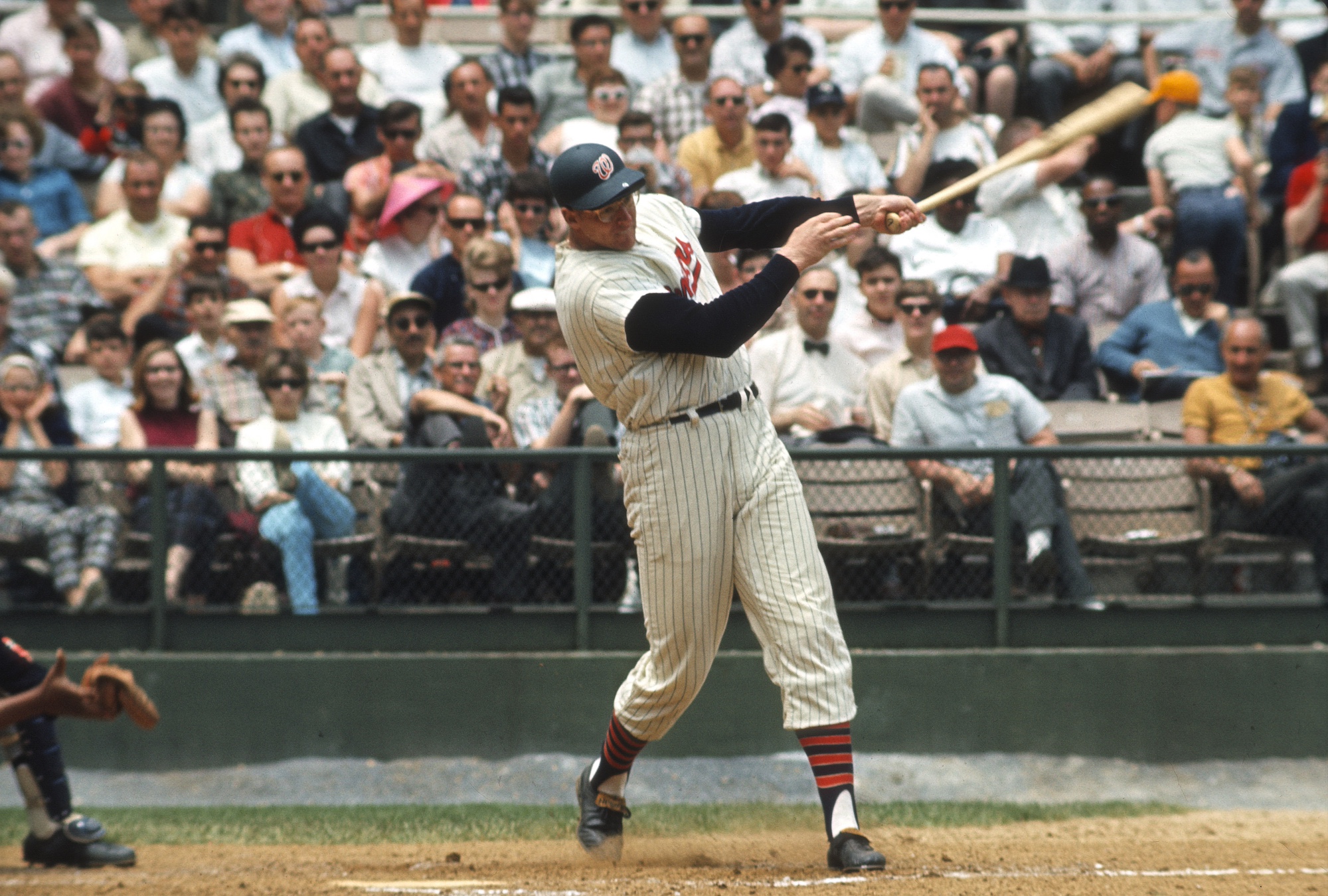

Frank Howard was larger than life and bigger than my dad.

Howard, a 6-foot-7, 290-pound slugger for several MLB teams and one Japanese club, died Monday at a hospital in Northern Virginia. The listed cause of death was complications from a stroke. He was 87 years old.

He was a left fielder for the expansion Washington Senators when I was a lad. I’ve been thinking about that team lately, what with the Texas Rangers making the World Series. And whenever you think about the expansion Senators, who fled D.C. for Texas in 1971, Howard’s always the first and often the only guy to come up.

It was an awful team, as bad as any in baseball history. The Senators had only one winning season in their 11 years in Washington, but lost at least 100 games four times. I was a fan for the franchise’s last few years in the Nation’s Capital, a time when the manager, Ted Williams, was a bigger draw than any player. (I remember that Williams’s memoir, My Turn At Bat, was a giveaway at at least two of the Senators games I attended.) The best-known names on the roster were troubled labor pioneer Curt Flood and Denny McLain, the worst two-time Cy Young winner ever. But both of them were on their way out of the game and only made news off the field by the time I was old enough to follow the Senators. Howard, who’d come to Washington in 1965 after seven seasons with the Los Angeles Dodgers, was the only star who played like one.

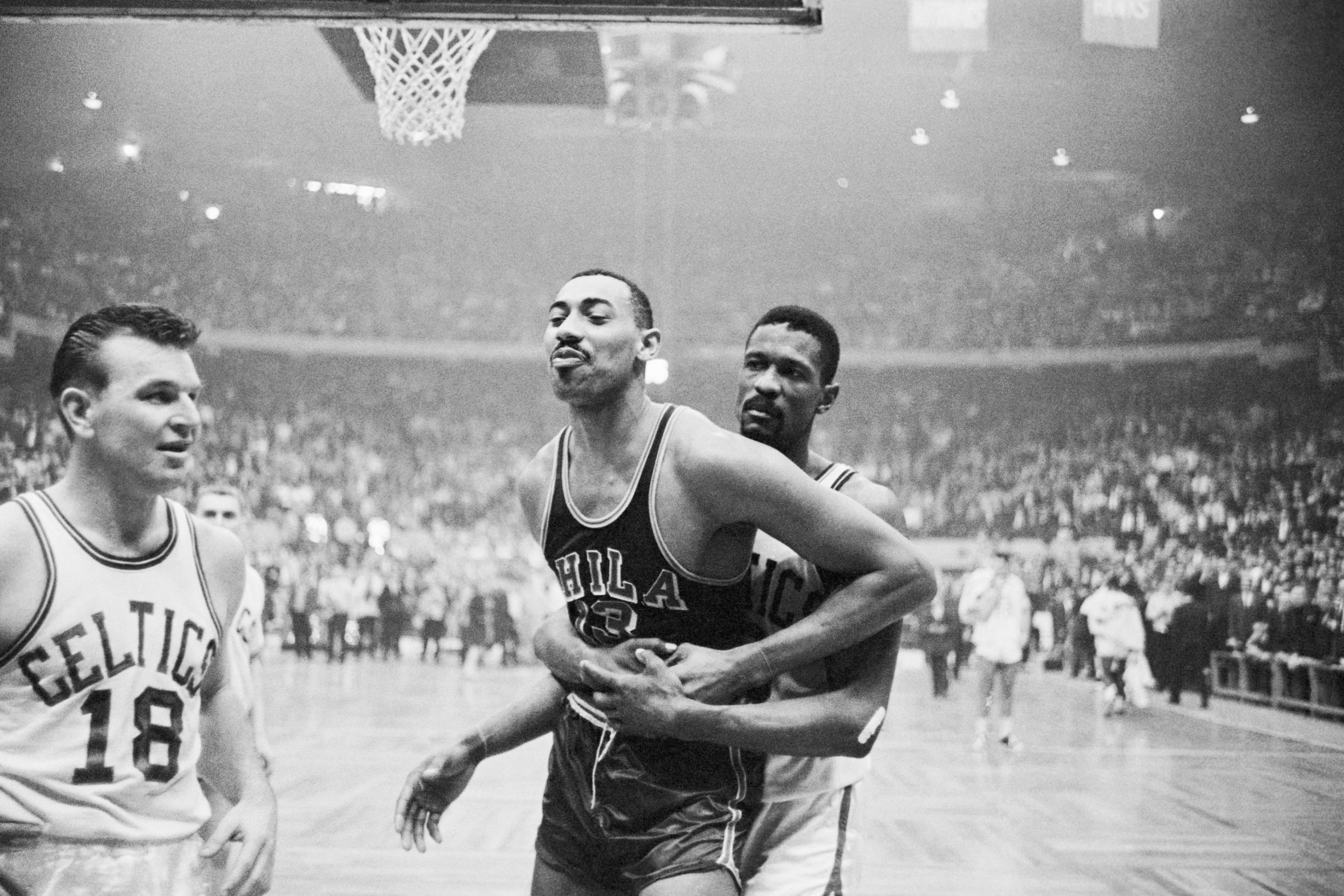

Howard was also the first famous athlete I ever got to see live and in person. I went to a few Senators games a year—odds were high a doubleheader or a particularly good giveaway was in play—and listened to the radio until bedtime for most of the rest. While the team around him was a mess, Howard always seemed above it all, physically and otherwise. He’d been a great basketball player at Ohio State before focusing on baseball, and looked better suited for the hardcourt. (Here’s Howard being introduced in March 1957 with the college All-American hoops team on the The Ed Sullivan Show, standing alongside Wilt Chamberlain and Elgin Baylor, a D.C. phenom who’d played at Spingarn High School literally across the street from RFK Stadium.)

Kids love giants and home runs, so all my neighborhood pals and I loved the quiet behemoth known as Hondo most.

There was very little memorable baseball played at the Senators games I attended. The only actual play I remember, in fact, is one from May 1971 where three Cleveland players ran into each other on a fly ball, turning a 200-foot pop-up into a home run and injuring themselves enough to require hospitalization. I just looked up the clips from that game and saw the paying crowd was 3,186. On a related note, the Senators would leave town at the end of that season.

Me and my buddies from Westlawn Elementary School had gotten in free as part of “Safety Patrol Night.” Howard played left field, and from the upper deck of the all-purpose stadium, where there was an overhang, you couldn’t even see the left fielder except during between-inning trots out to his position and back to the dugout. But there were a handful of seats painted white in the left field upper deck where gargantuan homers hit by the gentle giant had landed. So of course despite the obstructed view we sat in the left field upper deck that night. And we brought our gloves. (The box score says Howard went 1-for-3 in that game, with no homers but with a rare triple.)

There wasn’t much memorable baseball played at the Senators games I didn’t attend, either. Howard was a four-time all-star and led the major leagues in home runs twice in Washington, but through no fault of his own most of his homers in D.C. were meaningless.

Howard did take advantage of the few dramatic situations he found himself in, however. When Washington got to host the All-Star Game in 1969, for example, Howard thrilled the fans in attendance, including freshly inaugurated and soon-to-be-disgraced Vice President Spiro Agnew, by hitting a homer off Steve Carlton in his first at-bat.

But Howard’s biggest moment as a Senator came on Sept. 30, 1971, against the New York Yankees. The team's move to Texas had already been announced, and fans were angry. In the bottom of the eighth inning, with the crowd chanting “We want Bob Short!” to dishonor the hated owner who was about to take the team away, Howard took his final at-bat in his and the team’s last game in Washington. And he hit one more home run. With his team up 7-5, Howard stayed in the dugout for the top of the ninth. (You could say Howard’s end in Washington was a poor man’s version of Ted Williams’s farewell to the Red Sox.) The fans at RFK had seen enough. They stormed the field and began stealing bases and outfield grass and any other souvenirs they could grab of the soon-to-be-departed squad. The umps called the game and gave the Yankees a 9-0 forfeit win.

Howard played a few more years in Texas and Detroit and had one at-bat in Japan before calling it a career. He kept his home in the Washington area after baseball. He worked for a liquor distributor in Northern Virginia, where I grew up, and I would see him around now and then. He wasn’t easy to miss. I didn’t work up the nerve to approach him until I was a grown-up and went to a promotional appearance he made at a bar near my old neighborhood. I brought along a beat-up plastic Senators helmet I’d gotten as a kid on “Helmet Day.”

Most childhood heroes, when you finally get to meet 'em, aren't as big as you want them to be. Howard wasn’t most childhood heroes. He was still massive and still had the same buzz cut from his playing days. He was also incredibly nice.

“I try not to live in the past,” he told me as I showed him the helmet. But then he went ahead and talked about that last home game in Washington, just like I and everybody else who came to the bar just to be near our idol hoped he would.

“That one stands out,” he said.

So did you, Hondo.