This might go without saying, but: Massive spoilers for the entire series throughout, presumably including a third Villeneuve Dune film.

It may be hard for movie audiences to believe, but a series that begins with Lawrence of Arabia taking the Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test only gets weirder from there. I was at a low point in my cultural consumption when I started reading the Dune series—watching Marvel movies and mainlining old seasons of Survivor. Repetitive formulae. Paint by numbers. What a shock it was to start the second book and discover how radically different it was from the first. The once-nomadic Freemen had been suburbanized into uneasy post-war dissatisfaction. With each installment Frank Herbert attempted to re-reinvent the sci-fi novel, eschewing what he knew worked in order to try something new.

This had advantages and disadvantages. Not all the books were sufficiently plotted out, and he eventually got so caught up playing around in the sandbox of his characters’ thoughts that he lost sight of the original strengths of the series. But I kept reading for the thrill of Herbert’s vision—when it worked and when it didn’t, it was never, ever boring—to put myself in his hands entirely and see where he would take me.

The reach of Herbert’s imagination makes one thing clear: He never worried for a moment about a potential film adaptation. He never hobbled himself with concern about how his bizarre creatures and psychic manifestations could be rendered visually. It produced a singular series and has tortured generations of Hollywood executives.

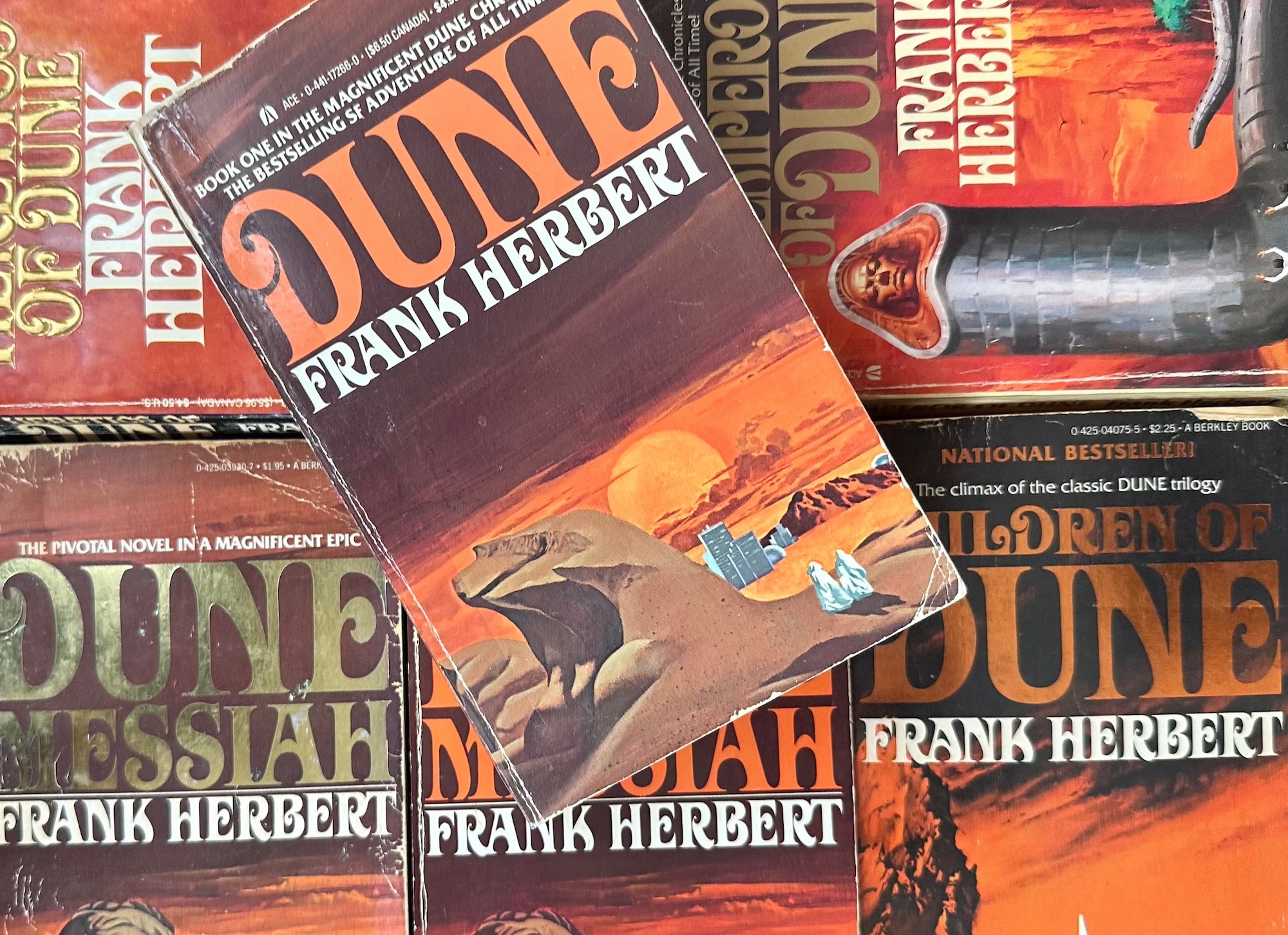

So I’m ranking the six Frank Herbert Dune books from most to least filmable. Note: The final two books in the main series, Hunters of Dune and Sandworms of Dune, co-written by Herbert’s son Brian, are not included in this ranking, mostly because I haven’t read them but also because they are widely considered to be very bad.

6. Dune (1965, Book 1)

They’ve filmed it. Twice. Q.E.D.

There’s a reason studios and directors have spent decades trying to crack how to get this story into the theater. The original sprawls in its political, ecological, and philosophical considerations but holds together through a clarity of purpose, its story pushing forward relentlessly through the digressions. The problem has always been that even though its plot moves like a freight train, there’s just so very much of it. Runtime has been the sticking point for every Dune production. The studio refused to let Alejandro Jodorowsky’s proposed version run more than two hours; he felt 10 to 14 would be appropriate. David Lynch’s cut of his Dune ran around three hours and producer Dino de Laurentiis balked, slashing it to two and kneecapping its chances with the public. Denis Villeneuve is the fortunate recipient of a changed industry paradigm—runtimes have crept upward (to the detriment of the product, broadly) and audiences have come to accept the splitting of a single book into multiple films. Combined his two Dunes run more than five hours.

Because we now have two versions of the first book on film, let’s consider some choices of adaptation that have outsize effects on the work. I saw Lynch’s Dune before I’d read the books. I had no memory of Lady Jessica, Duke Leto, Chani, Stilgar, Duncan Idaho, Gurney Halleck—the first hour of Lynch’s film is so incomprehensible the only characters who make an impression are Paul, the Harkonnens, and the Guild Navigator. Lynch seems to have had two goals for his production: to depict the Harkonnens as weird little freaks (mission accomplished) and to restage entire sequences from Lawrence of Arabia. (Fun fact: the first director ever attached to a Dune movie was Lawrence of Arabia’s David Lean, whom Lynch idolized.) Those preoccupations produced a film that contains several stunning vistas and action scenes but wastes far too much time on the Harkonnens bouncing around and cackling, at the expense of everything else. Lynch seemed unable to view the book as anything but inherently silly, and it shows.

I was fascinated by Part One of Villeneuve’s version because of its willingness to take it all seriously. I particularly like the Gom Jabbar scene, which skates right past the head-scratching idea of a pain box and just goes with it. He almost never makes changes to the story; his big decisions are what he leaves out.

Besides conveying the politico-economic situation more elegantly than I thought possible, Villeneuve’s main interpretive choice was to run the story at a fever pitch, an intensity of sound and image that borders on hallucinatory. But Dune is a story that gets literally hallucinatory when Paul and Jessica undergo the spice agony to unlock their prescient vision and ancestral inheritance. I went into Part Two expecting big things from these sequences—this was, to me, the crux of the difficulty of a faithful adaptation of Dune on film. How would Villeneuve show us, visually, Lady Jessica’s Reverend Mother awakening and the innumerable, contingent branching paths of Paul’s future? The answer is, he doesn’t! Villeneuve punts on these sequences, declining to take us into their minds save for a few underwhelming shots of Paul’s vision of following a woman through a field of corpses. This creates major problems in the back half of Part Two because Paul’s new abilities are underexplained, making both his motivations and hesitations hard to parse.

Dune the book is trippy—that’s its most tellingly from-the-60s quality. Villeneuve’s version is feverish but staunchly untrippy. It’s cocaine to Herbert’s mushrooms. I’d like to ask Villeneuve about this distinction. Is trippy a dead vibe, a relic of an era whose cultural import has passed? If so, the later books face an uphill climb to make it onto film, because the first one is downright normal by comparison.

5. God Emperor of Dune (1981, Book 4)

Dare to dream with me: A needle-drop montage sequence of Leto II killing successive Duncan Idahos over and over as the centuries pass. Imagine the worm-king crushing Jason Momoa beneath his great mass, ordering him speared by his Fish Speaker warriors, occasionally allowing him to live to old age when he performed his duties exceptionally. All the while, like, “Heaven is a Place on Earth” plays. Or maybe “All These Things That I’ve Done.” Too on-the-nose? I’m open to suggestions.

God Emperor of Dune is a paradox of filmability. On one hand, its story moves briskly, is mostly easy to follow, and its setpieces are suitably epic. On the other hand, this book marks the first major time jump of the series, eliminating every main character from previous installments save Leto II, Paul’s son—now a giant, 3500-year-old sandworm-human hybrid—and Duncan Idaho, cursed to an endless cycle of reincarnation by the Tleilaxu ghola tanks (read: clones). The ending of the previous book saw Leto II do what his father wouldn’t and decide to lead humanity down his Golden Path—the only possible future in which the species doesn’t go extinct, and one that will require many trillions of deaths to achieve—and fuse himself with a school of sandtrout (the tadpole stage of a sandworm), granting himself colossal strength and defense buffs and near-eternal life for the small price of metamorphosing into a man-worm. It’ll be a bold leading man who takes on that role.

Leto is finally showing his age, prone to reveries of stepping off the throne. One of his distant Atreides descendents, Siona, is involved in a resistance cell dedicated to deposing him. She is, it is revealed, the result of generations of planned breeding by Leto, which has given her the power of prescience invisibility, allowing her to operate outside the gaze of Leto and other seers who have strangled dissent for millennia. A lot of the book is a tour of Arrakis, now completely transformed—lush and green, its population confined to a non-mechanized, medieval standard of living. Leto, more and more seduced by the notion of his long-awaited death, and satisfied that his ultimate goal has been realized in Siona, makes a series of choices leading to his own destruction, his body dissolving back into sandtrout, all of which will carry a kernel of his consciousness locked in eternal dream.

Any adaptation of God Emperor needs to run on pure terror. One of the binds Herbert consistently put himself in is what I call the Sherlock Holmes problem: past a certain point of brilliance we can’t go inside a character’s head because they know too much. Herbert wrote about all-knowing supermen with access to the sum total experience of their genetic past and every future human act and still insisted on giving us access to their thoughts. Because he didn’t want to give the game away immediately, this resulted in some tortured writing in which Leto wonders about his plans and schemes while carefully talking around their specifics. It gets frustrating as hundreds of pages go by as he takes his entourage on a pilgrimage to the capital and stages elaborate ceremonies, the reader wondering if there’s a point to any of it. A film version could turn this defect into a strength by grounding us in more “mortal” characters like Idaho and holding Leto at arm’s length, a terrifying, capricious god whose intentions seemingly change with the breeze.

On a technical level, Leto II was once the insurmountable obstacle to filming this book. There is no way to visualize The Tyrant without recourse to some sort of effect. It was impossible to imagine audiences embracing a blockbuster centered on a big puppet or other practical effect. With modern CGI, Leto is possible. Whether audiences would be receptive to spending two-plus hours looking at the abomination remains an open question. I truly hope we get to find out.

4. Heretics of Dune (1984, Book 5)

Another big time jump, another new cast of characters. Herbert intended Heretics to be the first in a new trilogy, for a total of seven books; he died after writing the sixth, leaving Heretics and Chapterhouse as perplexing and unfinished curios. Another 1,500 years have passed. Leto’s empire has crumbled and people have spread into the unknown depths of space, lost beyond contact or knowledge. The Bene Gesserit stepped into the power void, which makes them the de facto protagonists. But now ships are returning from the Scattering. Among those returning are a powerful group of women called the Honored Matres, red leotard-wearing nuns who can enslave men with their advanced sexual techniques. I’m not kidding when I tell you that there are descriptions in this book of Honored Matres pulsing their vaginal walls to bring men to orgasm on cue. You know, normal book things.

The Dune books are weird, but there are two different kinds of weird. There’s the psychic children, worm-god kind of weird, which I dig, and there’s the kind of weird where a sapphic army attempts to conquer the universe using the power of gorilla grip vaginas, which is vaguely embarrassing. The way character after character looks askance at the Honored Matres’ weaponization of their sexuality as if there could be nothing more appalling has the distinct flavor of Herbert working through an extramarital dalliance and trying to absolve himself of blame. There’s so much misogyny baked into these villains that I struggle to imagine how they could be brought to the screen, or who would want to. There are reasons your Dune-reading friends rarely talk about Books 5 and 6.

That said, if some heroic writer could turn this into something digestible, then this story has the building blocks of a good film. To launch his new trilogy, Herbert cribbed from the best: the original Dune. In a mirroring of Paul and Jessica’s desperate flight from Arrakeen, yet another Duncan Idaho clone, this one still an adolescent, and his Bene Gesserit attendant Lucilla are forced to flee an Honored Matre attack and spend the rest of the book trying to reach safe haven. Along the way Duncan unlocks a secret ability to sexually ensnare Honored Matres right back, while another Atreides descendant, the general and mentat Miles Teg, gains the ability to go Super Saiyan, fighting faster than the eye can perceive. In another storyline, a little girl is discovered on Arrakis who can command the sandworms. All of this is crazy, but at least it involves characters having adventures, rather than just sitting in rooms and thinking.

3. Dune Messiah (1969, Book 2)

Denis Villeneuve has said repeatedly that he intends to adapt Messiah before exiting the franchise. After seeing Dune: Part Two this weekend, I understand his determination both more and less. It’s clear the political side of the story is what interests him most—the maneuvering of the Great Houses and Paul’s rise to command the Fremen. Messiah offers this in spades, as Herbert shifts forward 12 years to a point where Paul’s military grip on the known universe is absolute but palace intrigue abounds.

But this book also ratchets up the mysticism, philosophical mumbo-jumbo, and exercise of Paul’s mental powers, all of which will have to be depicted this time around—they’re too fundamental to the story to ignore. Villeneuve will have to reckon with Paul’s sister Alia, whose exclusion from Part Two represents his biggest break with the source material. Born with adult consciousness and a Reverend Mother’s store of other lifetimes, Alia is the high priestess of the faith of Muad’dib; watching her perform the sacred rites for a rapt crowd is one of the highlights of the book. So far Villeneuve has not demonstrated any excitement for this gnostic side of Dune. He’s a materialist playing in a metaphysical sandbox.

In any case, the real challenge of bringing Messiah to the screen is that it’s simply a mess. The story is schematic and disjointed, with little apparent relation between its careful set-up and its sloppy denouement. Herbert clearly went in with one goal—kill Paul—and while he does accomplish that, sort of, it’s at the expense of everything else. At least this book introduces the genetically altered Tleilaxu and brings back Duncan Idaho in his first ghola incarnation. I found myself missing Momoa in the second movie.

Also, Lady Jessica does not appear in Dune Messiah. This is unacceptable, both because she’s the best character in the entire series and because I’m not ready for a film without Rebecca Ferguson. I would initiate galactic jihad if she asked me to.

2. Chapterhouse: Dune (1985, Book 6)

This is peak characters-sitting-in-their-office-and-thinking Dune. The story picks up around a decade after Heretics, with the Bene Gesserit and the Honored Matres locked in a stalemate. The Honored Matres have rampaged through the galaxy destroying entire planets and eliminating the Bene Tleilax wholesale. The Bene Gesserit hide on a cloaked planet, their resources and options dwindling. For page after page, Reverend Mother Darwi Odrade considers the state of play and develops a plan to turn the tide in their favor. It’s so boring!

There’s some potential in a Chapterhouse adaptation. The cold war eventually heats up when the Bene Gesserit strike back, attacking Gammu and another planet, led by a child-ghola clone of Miles Teg. Herbert’s descriptions of these engagements are snore-inducing, but they are a starting point for action sequences. The challenge would be grounding these battles in particular characters. I guess it would have to be Teg, although the image of him as a toddler traversing the battlefield on the shoulders of his lieutenant is an extremely silly one.

There are other problems, most notably that Herbert was getting old and weird and this is the book where decided he needed to talk about Jews. Remember above, how Leto II devoted generations of eugenics to developing an Atreides family line invisible to prescience? Early in this book, out of nowhere, Herbert declares, “There’s actually another group with this ability. It’s Space Jews. They developed it naturally when they got so good at hiding on Old Earth, due to all the pogroms.” When Lucilla, fleeing Honored Matre attack, takes refuge with a character called just The Rabbi and his daughter Rebecca, she’s immediately betrayed and turned over to her enemies. What’s especially bizarre is this plotline doesn’t contribute anything to the larger story. At least it could probably be excised from a film version without notice. Just a total unforced error on Herbert’s part.

1. Children of Dune (1976, Book 3)

God help whoever inherits this series from Villeneuve. That poor soul is more screwed than a Harkonnen soldier stranded deep in Arrakis’s southern wastes on a plain of drum sand.

Nine years after Paul, blinded, walked into the desert to offer himself to Shai-Hulud, his daughter Ghanima and son Leto II are far from ordinary children. Being the offspring of a Kwisatz Haderach caused them to awaken to full consciousness before birth, like their aunt Alia. To an observer they appear to be 9-year-olds and are treated as such, to their constant frustration. They have inherited the Bene Gesserit gift of ancestral memory, meaning that not only do they possess mature minds but ones that reach back into the distant past.

The memories of these innumerable ancestors allow the siblings to adopt their personae at will, wearing their personalities as so many masks. Leto and Ghanima play elaborate imitation games in which they trade sophisms back and forth as they slip between identities, trying on and casting off the personalities of ancestor after ancestor. At one point, the persona-memory of Literally Agamemnon demands recognition, confirming that their last name is Atreides because they truly are the children of Atreus, their lineage dating back to heroes of the Homeric epics.

These scenes are some of my favorite in the entire series. They are also about as unfilmable as I can imagine. Any version that insists on maintaining a vision of external reality is doomed to failure: It would just be two kids sitting on a cliff saying precocious, incongruous nonsense back and forth. That would have the charming quality of the end of Donald Barthelme’s The School when the grade-school kids suddenly start talking like grad students (“but isn’t death, considered as a fundamental datum, the means by which the taken-for-granted mundanity of the everyday may be transcended in the direction of…”) but it wouldn’t, you know, work as a movie. Not a big-budget box office blockbuster, anyway.

What’s required instead is a willingness to get a little more conceptual with it. You know that part at the end of Barbie where the world collapses into a series of increasingly abstract spaces until Margot Robbie and Rhea Perlman are talking in a gray void on the border between being and non-being? I imagine something like that, with Leto and Ghanima facing each other, both flanked behind by their endless horde of forebears. As they shift personae, the new one advances from the crowd and steps into their body, taking it over. This idea of inhabiting spirits is strikingly similar to Killer BOB and the Giant from Twin Peaks possessing Leland Palmer and the bellhop. So it is settled: We must give Children of Dune to David Lynch.