Doechii’s YouTube channel has 1.85 million subscribers. Her most recent video, a new single called "Nosebleeds," was posted shortly after she became the third woman ever to win the Grammy for Best Rap Album on Sunday.

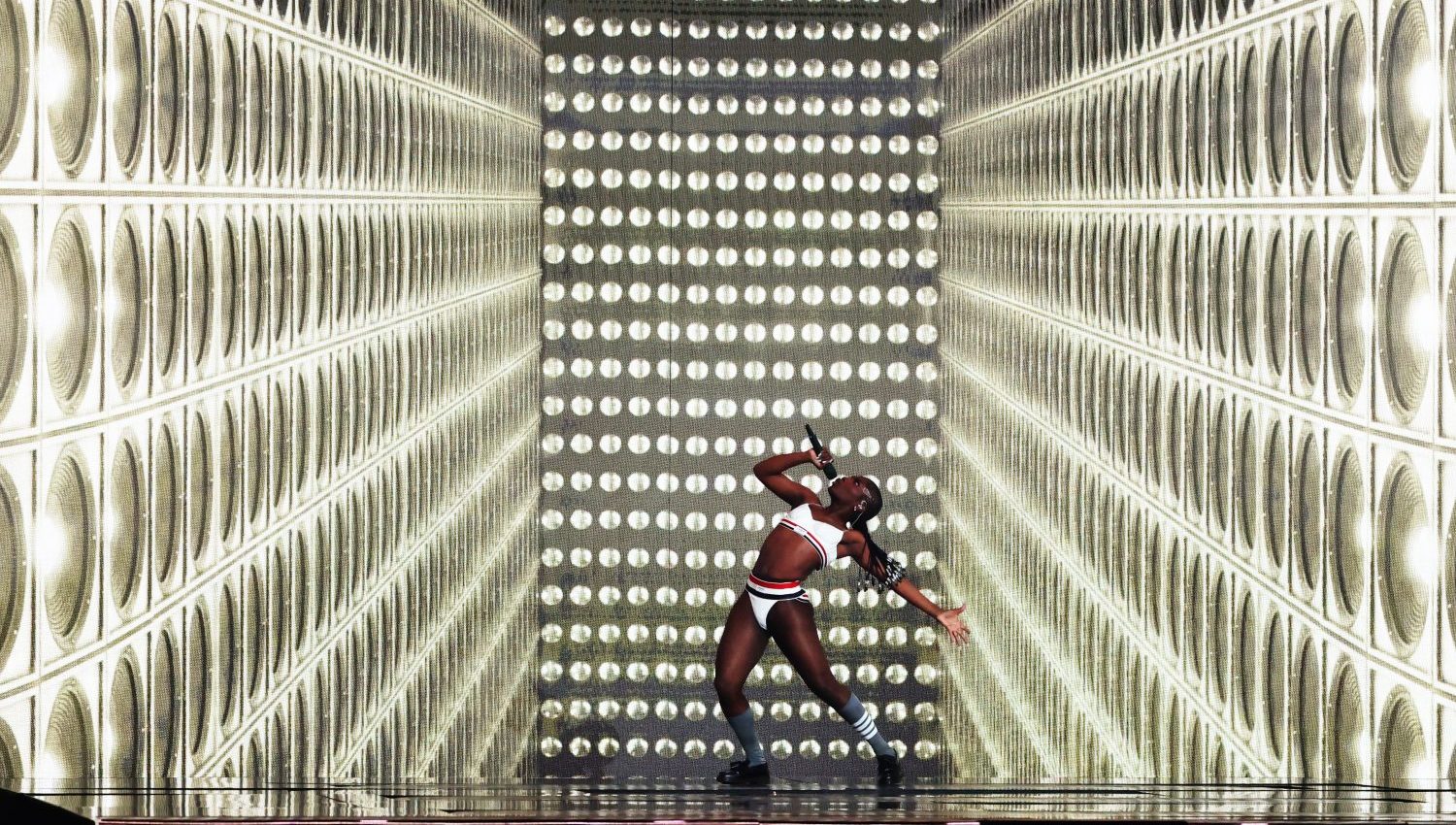

I keep replaying moments from her Grammy performance of "Catfish" and "Denial is a River"—the shapes she made with her body while standing on the platform above her throng of dancers, the moment her dancers split her Thom Browne suit to reveal a stark white underwear set, and her Fosse turn in the bright lights. Doechii's performances are crisp and deliberate; at 26 years old, her creative vision seems fully realized already, executed with a precision as tight as her signature face tape.

Things get less polished as you scroll past the Vevo music videos, album tracks, and live performances on the YouTube channel, which Doechii started in 2014. Buried deep but still online are vlogs she posted as a high schooler of no particular fame, documenting her life in Florida in videos with titles like "Tattoo Experience: Pain, Meaning & MORE!" and "BCU College Orientation VLOG."

Around 2019, the videos started to evolve, more explicitly discussing Doechii's developing life as an artist. In one video from April 2020, she rents an Airbnb for a solo business retreat. There's a clip where she's perched on the twin-sized bed with her laptop and a plate of macaroni and cheese while she explains her plan to form an LLC.

"I want to turn Iamdoechii into an LLC and push my intellectual property, my products, my music, my shows, et cetera, and also tangible products like merch," she says. "And I think it's very important for me to test my buying power right now as an artist and as a creative in general because at the end of the day I am making art, but I want to make a living off of selling my art."

I feel like I shouldn't be able to watch Doechii drinking a beer in her bonnet while she makes mood boards on her free Canva account. It pierces the illusion that she emerged fully formed, a Botticelli's Venus on the global stage. The videos do what the best artists' diaries do: They make legible the labor of becoming an icon. You steal glimpses of how it started, what moments of failure prompted evolution, and at a certain point, you start to recognize the public figure you know.

On my bookshelf I keep a small collection of artists' diaries, which I never get sick of reading. I am obsessed with eavesdropping on the conversations they hold with themselves as they do the work of becoming who they are. In Reborn, a published volume of Susan Sontag's diaries between the years 1947 and 1963, she writes, "Will I never learn from my own stupidity! I heard today a lecture-recital on Browning's dramatic monologues … How ignorant of and snobbish about Browning I've always been!—Another author to work with this summer…."

In a 1932 entry in the first published volume of her diary, Anaïs Nin fumes about an interaction with René Allendy. "Allendy is mistaken not to take my imagination seriously," she writes. "Literature, adventure, creativity are not a game with me. I may be basically good, human, loving, but I am also more than that, imaginatively dual, complex, an illusionist."

There is something almost illicit about having access to an artist's internal monologue, and accessing it in video form makes it feel all the more immediate. Doechii's vlogs differ from Sontag and Nin's published diaries in one major way: intention. Artists' diaries are often published posthumously, after they've become widely recognized enough to merit publishing juvenilia. Before being published, these diaries must undergo a process of editing and culling to prepare them for public consumption. YouTube vlogs, no matter how small the audience, necessarily contain within them the presumption of an audience. That the medium Doechii chose to document was on the social internet speaks to her intention: She always meant to build an audience.

I say this with great love and respect for Doechii: I am obsessed with the level of delusion in a lot of these videos. She hadn't made it (yet), but you can see the steely focus that would lead to that Grammy performance five years later. In one video in which she decides to form a creative collective with her collaborators, they talk about winning Oscars and Grammys one day. If I didn't know how this story ends, I might roll my eyes. The grandiosity with which she talks about her aspirations takes you aback for a second. Her audacity is shocking because she's a woman with a laptop in Florida, not the superstar-in-the-making who took everyone's breath away on Sunday.

With all the bad the social internet has brought society, it also affords the privilege of being able to sift through the layers of audiovisual detritus a person produced in the moments before they made it. I wonder what is lost in the documentation, though, when those layers are explicitly performances from the very beginning for an imagined—or real—audience.

The last official vlog Doechii posted to her YouTube channel was in August of 2020. The video is titled "Crunch Time: 7 days till the shoot." It opens with a shot of Doechii sitting at a table with two other women, hair stylist Symone Akiboh and creative director Char'nae Davis. The light is dim, and they're looking at their laptops, talking through plans for Doechii's "Yucky Blucky Fruitcake" video, which they are a week out from shooting.

"I feel like we're being so creative with the minimal stuff that we have," Doechii says. "We only have three scenes and it's gonna be dope." It was.