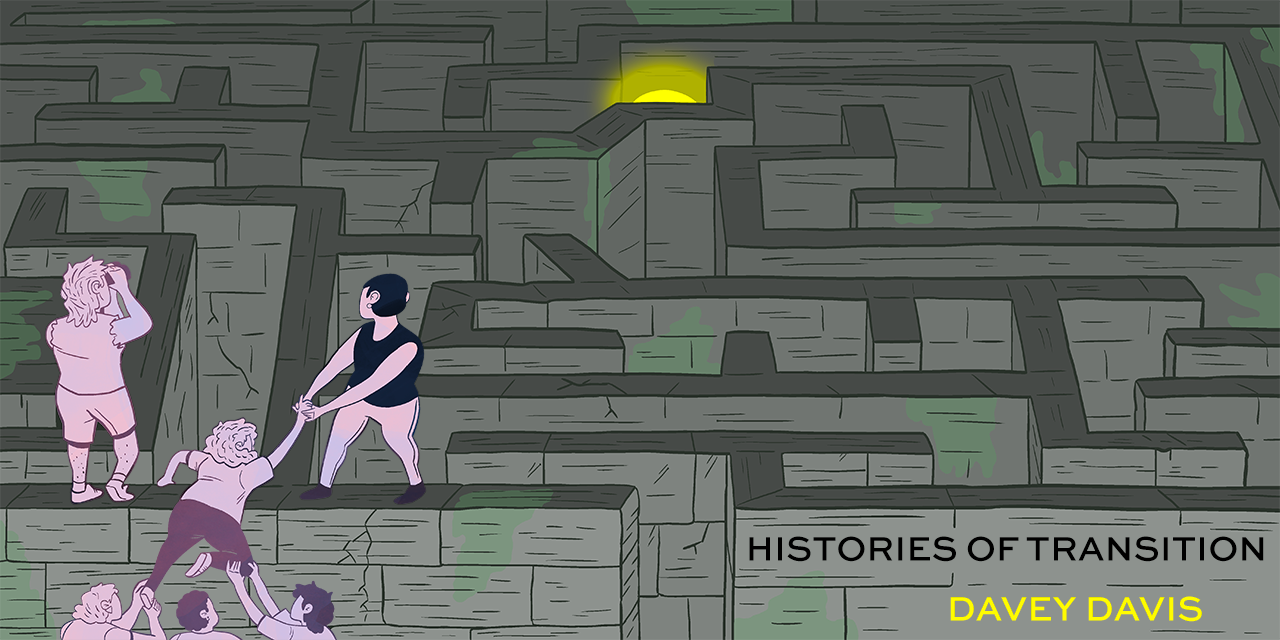

Histories Of Transition is a series spotlighting the experiences of trans people as they've worked to exist within structures that don't want them to.

In 2010, when I was 22, I asked a primary care doctor at my Bay Area university about top surgery. He looked like he’d walked in on a ghost taking a shit. “There are chat rooms for people like you,” he said, scowling as he rushed out the door. (Doctors: 1, David: 0̷)

At a different school the following year, I went to student psych services to ask about surgery again. Gimlet-eyed as a new widow, the therapist compassionately declared that I must be confused, seeing as how I didn’t want hormones or even think of myself as male. (It was the early teens, when gay people were calling it “genderqueer.”) I was also having sex with men—how could I keep doing that without breasts? Even so, TRANSSEXUALISM lived indelibly on at the top of my Kaiser Permanente medical chart. (Doctors: 2, David: 0̷)

After that, I went a little crazy and gave up for a while. But seven years later, when I was ready to try again, a lot had changed since the “trans tipping point,” the Obama administration’s expanded healthcare coverage, and Trump’s election. The social worker who did my intake at Kaiser Oakland was trans; he was warm, kind, and didn’t care about my sex life. The recently increased demand for gender-affirming surgery had drawn an influx of plastic surgeons with no trans expertise. On the one hand, this meant I didn’t have to wait more than a few weeks for an appointment, which I went to alone; on the other, my prospective surgeon misgendered me a bunch before breezily committing a handful of HIPAA violations against his other trans patients. Back to the drawing board. (Doctors: 3, David: 0̷.5)

Another local surgeon hosted a monthly top surgery education seminar at Kaiser, where happy trans mascs joined her to show off their perfect chests. I would have to take their word for it, since most of the few transsexual friends I had were girls. At my intake with the surgeon, which I again did alone, she was friendly, more-or-less trans-informed, and assured me she could give me a periareolar procedure. I felt confident in my decision to go with her. (Doctors: 3, David: 1.5)

The surgery went badly. The surgeon said the swelling would go down, but when it did, there was still remaining tissue, only now it looked like it had been in a knife fight. My chest had been too large for the peri she promised me. My friends, one of whom was beginning the long and complicated process of getting bottom surgery, did their best to console me, but it all felt too big. I wished that the surgeon would apologize, or even just acknowledge what had happened, but her office seemed to have lost my number. (Doctors: 4, David: 0̷)

Six months later, I moved to New York and sought out Alexes Hazen, a surgeon with a reputation for doing good work and being close to the community. Among the New Yorkers I began meeting were patients of hers, real live trans people who were happy with their results. Desperate to fix my chest, I began the process again. (Doctors: 4, David: 1)

My insurance fought my revision for months. They wanted before-and-after photos from my first surgery in addition to the ones my original surgeon provided, so I was forced to scour old sexts for images of my breasts so a medically licensed bureaucrat could “assess” them before determining … what? This was never explained. Still, after months of cryptic phone calls and anxious waiting, the bureaucrat submitted his approval a week before my date. A few days later, my insurance company called again with an eleventh-hour demand for two letters of support from mental healthcare providers, which, thanks to some old therapists, I somehow finagled overnight. My new surgeon’s team told me they’d never fought insurance so hard over a covered procedure (I still paid $5k out of pocket, each, for both surgeries, though neither hospital charged interest and both worked with me to make payment plans). But by then, it didn’t matter: Dr. Hazen did beautifully, and now my chest makes me so happy that I don’t even think about it anymore. What’s more, when I die god will give me a weapon and a few hours of sunshine to do what I will with that bureaucrat. (Doctors: 6, David: 1 + a hammer)

By this time, I had finally come around on hormones, which kick so much ass. (I can’t even tell you how amazing they are. You should start them, like, right now.) The earliest informed-consent appointment I could find was at Planned Parenthood in Brooklyn, though I still had to wait three or four months for it. At PP, nothing was ever on time, but the providers treated me like a person. Many were queer, a few were trans, and some had trans people in their lives. They taught me how to give myself my shot, though a butch friend was doing them for me at home. When I had trouble getting my hormones at my pharmacy—insurance again—PP gave me a direct line so I could quickly call for doctor reauthorization, which was my insurance’s excuse whenever I hit that monthly wall. (Doctors: 6, David: 2)

With my surgeries and hormones figured out, I felt like I was finally getting somewhere when my first-ever PCP recommended that I transfer my trans healthcare from PP to Mt. Sinai, where I saw her. There was a real endocrinologist at Mt. Sinai, my new PCP told me, which meant the level of care would be much better than what I’d get at PP—and really, shouldn’t I be taking advantage of the insurance I got through my job? (Doctors: 7, David: you already know what’s happening next)

Sometimes … things that are expensive … are worse. For my first visit to Mt. Sinai endocrinology, I was not seen by the “real” endo, but rather a clique of nervous residents who knew less about HRT for transsexuals than I did, and who then proceeded to fuck up my dose. The “real” endo, who I’ve still never met in person even though I’ve been her patient for three years, is prone to month-long vacations without warning, meaning I can’t get my hormones at all. PP isn’t perfect, and we’ve all heard the stories about Callen Lorde, but I often think about going back to a community clinic. (Doctors: 1 million, David: ??)

Do trans people need doctors? Technically, yes. But maybe the real trans healthcare was the friends I made along the way: the ones who advocate for me while I dissociate on the exam table, who share their hoarded hormones and syringes, who supplement the often ignorant, and sometimes violent, “care” that so many doctors and their minions are addicted to. If you’re considering medical transition, you can probably do some of it without doctors; depending on where and who you are, you may have to. But it’s much harder to do it without other trans people. Don’t know any? Find some. I know you can.