Ding Liren is the 17th world chess champion, after defeating Ian Nepomniachtchi in tiebreaks in a rollercoaster world chess championship match in Astana, Kazakhstan. Nepo had all but sewn up the match twice in Games 12 and 14, but Ding fought back to miraculously take the match to overtime, and secured his place in chess’s Elysian Fields with an utterly cold-blooded win in the fourth rapid playoff game.

Let’s recap Games 8-14 and the tiebreaks, with bold type representing moves which actually occurred in the games, and italics representing hypothetical variations which could have occurred but did not. In case you missed them, catch up with the match with our preview and recap of Games 1-7.

Game 8

Ding Liren had melted down in Game 7 of the match, squandering five of his remaining five-and-a-half minutes calculating one of the nine moves he had to make in that period, gifting his opponent a precious win and the match lead out of thin air in a position where Ding had the advantage. On the intervening rest day, Ding would need to—yet again—find a way to regain his composure.

With Nepo now leading by three games to two, the Ding rollercoaster continued during Game 8, because, as Mr Redford covered previously, a large chunk of his precious opening ideas were making their way around the internet while he and Nepo sat at the board.

The players played what would become a fateful opening: in a line of the Nimzo-Indian, Ding played rook to a2 on move 9, a move which the Lichess.org database showed had never previously been played between masters. Expand the search to all players, however, and it turns out that it had occurred in one game between anonymous players with low ratings. After a few more clicks, an internet sleuth discovered that the players in that game had played 72 head-to-head games on Lichess (which, incidentally, is the best chess website and the one that you should play your games on) in early 2023, a dozen of which featured the 4.h3 novelty played by Ding in Game 2 of this match, a move also which had also never before been played between masters. From there it only took a little bit of digging to come to the conclusion that the accounts belonged to Ding and a training partner (presumably world No. 12 Richard Rapport), and that the games featured some of the ideas that they had been prepping for the match.

It was unforgivably sloppy stuff by Team Ding: it’s possible to play private games on Lichess as a guest (meaning the moves would not be saved in any database), or even, as Lichess themselves suggested, to set up a private server using Lichess’s open-source code. (Teams have got to be vigilant in these high-stakes matches: long-time readers will recall a portion of Fabiano Caruana’s prep being accidentally leaked in a hype video during the 2018 world championship.) Ding finally displayed some diplomatic nous when asked about the leak in the post-game press conference (his team having quickly alerted him to the situation immediately after the game), and he played a straight bat, feigning confusion at what games he was being asked about.

Because I love you all, I clicked through all 72 of the games played by Ding and his partner, and they featured some cool nuggets, including a crazy line in the Petroff where Black wins an exchange in an unbalanced position that the computer claims is close to equal, a 6.h3 Najdorf where Black was detected as cheating after 15 moves, and three games which featured the line of the anti-Berlin ultimately played in Game 9. (I also like that one of the usernames, “FVitelli”, appears to be named after a company which makes classical musical instruments, though I can’t find anything to suggest that either Ding or Rapport are musicians.)

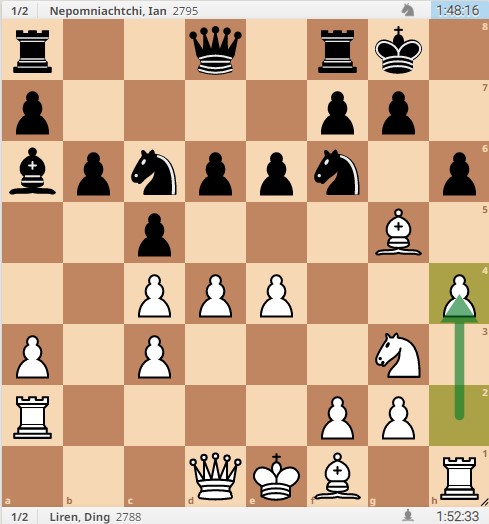

Anyway, back to Game 8: Ding played his “cannonball” (as he later described it) novelty rook to a2, and a little later showed a cool idea with the temporary piece sacrifice pawn to h4!

This allows Black to capture the g5-bishop, but after White recaptures the pawn with hxg5, Black’s attacked knight can’t move and must sacrifice itself for the cause. Why? If e.g. knight to d7, White has the simple queen to h5!, and checkmate on h7 is inevitable: Black’s pawn to f6, trying to create an escape square for the king, is calmly met with pawn to g6, and the f7-square is covered and it’s all over, red rover.

Nepo avoided that variation, however, and the players tightrope-walked through a razor-sharp early middlegame, with Ding declining to castle in favour of building up his attack on Black’s center. He manufactured a passed pawn (that is—one with no enemy pawns ahead on the same or adjacent columns) on the d-file, and for the second time in the game made a funky rooklift with rook a3. (Pushing your rook up the board by one or two squares is a type of move played exclusively by either rank beginners or world-class players.)

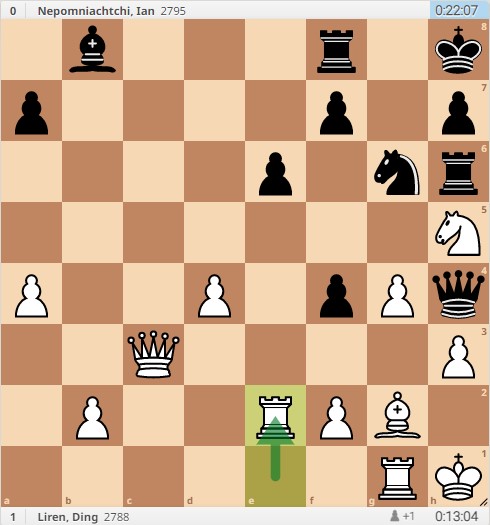

After a loose move bishop takes knight on e4 by Nepo, it looked as though Ding might have calculated his way to a winning plan, when he followed up queen recaptures on e4 and knight f5 with the gorgeous rook to d2!

While it’s tempting when launching an attack to constantly look for flashy knockout blows, sometimes the best moves in complicated positions are the quiet ones. Here, White is temporarily passing on the obvious queen takes pawn on e4 with check, since it turns out Black’s f-pawn can come forward to defend, and after a few trades on the f6-square the attack fizzles out, with White’s d-pawn able to be rounded up in short order. Instead, Ding followed the maxim that all your pieces should be invited to an attacking party: the rook is now in the game defending White’s dangerous d-pawn, and, crucially for the variations to follow, White’s queen remains attacking the a8-rook.

The win was on for Ding, though after a trade of rooks on h8, he played only the second-best continuation by pushing his d-pawn rather than echoing his earlier quiet move with rook to d3!, threatening rook to h3!, and which likely would have ended the game on the spot. White could then have marched his d-pawn, since he’d control both a8 and h8, and Black could prevent either the pawn queening, or the king getting mated, or suffering huge material losses, but not all three.

Nevertheless, Ding still firmly had the upper hand, and was proceeding with the attack when Nepo threw out a Hail Mary: with the insane queen to h4?! (leaving the rook on d8 completely unguarded), he thought he had found a perpetual check:

A game ends in a draw if one side can generate an infinite loop of consecutive checks which the opponent cannot escape, and where no checkmate can be found. Nepo thought he had found one, with the plan that if White takes the unguarded rook on d8, queen e4 check, rook e2, queen b1 check, king d2, queen b2 check, king d3, queen b1 check, rook c2, queen d1, and then the queen toggles between b1 and d1 as the rook can do nothing better than alternate between c2 and d2 to defend the checks:

However, incredibly, White instead has the insane king to e4!!, voluntarily giving up its rook with check, and there’s somehow no way to embarrass the king in the center of the board. Queen takes on c2 check is met with the block bishop d3, and while knight d6 is a check, it interrupts the black queen’s line of communication with the white d-pawn, and the checks have run out—king e5!!, and although White loses its bishop with queen takes on d3, White simply has queen to f6 check, and the d-pawn queens on the next move and the Black can resign.

It was an absolutely insane variation which any normal human would miss—it’s not every day you expect to calculate a line where you sacrifice two pieces and station your king in the middle of a board with an enemy queen and knight on the attack. However, super-Grandmasters are not normal humans, and as one of the best calculators in chess we might have expected Ding Liren to find this defense. But, as he stated in the postgame press conference, he had his temporal meltdown in Game 7 firmly in mind during this Game 8, and “considering [Game 7’s] loss”, he was trying to play quickly, and only calculated the line up to the position in the above diagram, believing it was indeed a perpetual. (Nepo stated that he thought it was a true perpetual when he played queen h4, but subsequently found the winning defense, meaning that he had to show his best poker face and hope that Ding would believe in his plan.)

And so, Ding’s king d1, shielding the white king from any checks from the black queen, killed most of his advantage, because it allowed the black queen to take the pawn on g5, re-establishing her defense of the d8-rook. After some more sharp maneuvering, the players liquidated into a drawn endgame and shook hands for a draw on move 45. What a save by Nepo!

Once again, it was a game where Ding’s mindset, rather than his chess, seems to have cost him at the board. That’s not to short-change Nepo’s inventive, if flawed, defensive idea, and it was great to see one of our players digging their heels in on defense and grinding their way back to a draw. We hadn’t seen truly elite defense so far in this match—as entertaining as the decisive games had been, it had largely been the case that the side who managed to find a middlegame advantage had been able to convert it into a full point, without having to overcome superhuman resistance. Nepo’s save was the first example to the contrary. Would Ding live to rue this missed win?

Game 9

Ian Nepomniachtchi had the white pieces in Game 9, and after he again opened up with 1.e4, Ding Liren replied with e5 (apparently it was too early for Ding to start playing for sharp complications with the Sicilian Defense), and after knight to f3, knight to c6, bishop to b5, and knight to f6, we got the first appearance of the Berlin Defense in this match. Vladimir Kramnik immortalized that opening in his successful 2000 world championship match against Garry Kasparov, playing it four times for four draws as the greatest to ever push a pawn could find no way to even begin to build a winning position against it. The Berlin has been inescapable in high-level chess ever since, with its reputation for solidity only enhanced in the supercomputer era. “Solid” can often equate to “boring” in this context, but Game 9 was a fine counter-example where we were treated to a sharp and double-edged position.

After Nepo’s 4.d3 (the so-called Anti-Berlin, because it avoids the “Berlin Endgame,” where queens are traded off the board on move 8, which was featured in each of those four Kramnik-Kasparov games), Ding played the move bishop to c5 which had been featured in the training games leaked the day before. That move itself isn’t at all novel (it’s the most common move in the position, in fact), but given Ding’s boldness in playing something from those games notwithstanding they had been compromised, Nepo might not have wanted to find out what Ding had in store, and he deviated from those games’ path with 5.c3, though Ding seemed to remain well within his preparation until into the middlegame.

The position quietly developed tension, until one loose move from Ding (moving his rook to b8 on move 17) meant it seemed as though he was one tempo behind the action, with Nepo amassing forces against the Black king, with commentators wondering whether Ding would be able to consolidate his defenses before the cavalry arrived. Ding had assessed that he would survive Nepo’s attack, however, and so when he greedily grabbed a pawn with pawn takes on a4, the position exploded:

Bishop takes on h6!, and the pawn can’t recapture, because then simply queen takes knight on f6, and the Black king is mortally exposed. Ding continued knight to c5, and after Nepo’s knight to g6 (the f-pawn is pinned by a2-bishop and so can’t capture the knight), all the white pieces have come for a party in the black king’s house. Ding found the double-edged rook takes on b2!?, which is an interesting multi-purpose move, as while it doesn’t directly contribute to the defense on the kingside, it does threaten to capture the a2-bishop, meaning that the g6 knight could then be captured (the f7-pawn no longer being pinned), leaving Black with extra material and an advantage. In the long-term it also had the benefits of capturing a pawn and turning Black’s two a-pawns into passed pawns.

Ding had therefore managed to find his groove amongst the chaos, and after a trade on f8, Nepo’s bishop back to g5 seems to have been an admission that his attack didn’t have enough venom to be fatal, a short-term moral victory of sorts for Ding.

The players then tangoed through a tense patch where White’s bishop pair bothered Black’s advanced b-rook, with Ding at one point offering Nepo an exchange:

White’s c4-bishop is attacking Black’s b5-rook, and with bishop to e6 Ding expected Nepo to take the invitation to capture the more powerful piece, with the idea that Black’s 3-versus-1 queenside pawn majority would be adequate compensation for the material deficit. The computer seems to like that continuation for White, though Nepo’s bishop takes on e6, avoiding an unbalanced position, was fine.

Ding calculated a path to exchange the queens off the board, and after a mass trade the players entered an endgame where Nepo had a 3-versus-2 pawn majority. The last rooks were traded on move 52, and we had a knight endgame:

The saying goes that all rook endgames are drawn, and although knight endgames often end the same way, they’re trickier: it’s more difficult to calculate long lines involving the horses’ L-shaped jumps than orthogonal rook moves, and a player can easily go astray if they miss a key continuation from afar.

The players were on the ball, however, and they played confidently and quickly like the 2800s they truly are, with plenty of time still on their clocks, after receiving an extra 15 minutes plus a 30-second increment per move on move 61. Some straightforward (for them) maneuvering later, and the players shook hands for a draw on move 82, the longest of the match so far.

The fact that this game lasted so long potentially indicated that Ding’s head was once again screwed on straight, since while those positions should be holdable for super-GMs, they don’t calculate themselves, and Ding never looked like putting a foot wrong. He had managed to hold another game with the black pieces, but with only five games remaining, the end of the tournament was starting to loom near, with Ding needing to find a win to even the scores.

Game 10

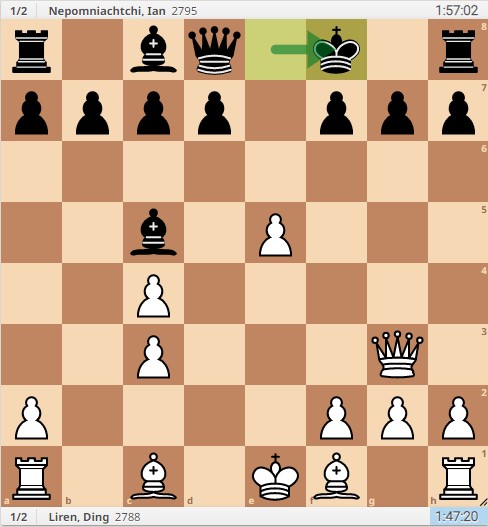

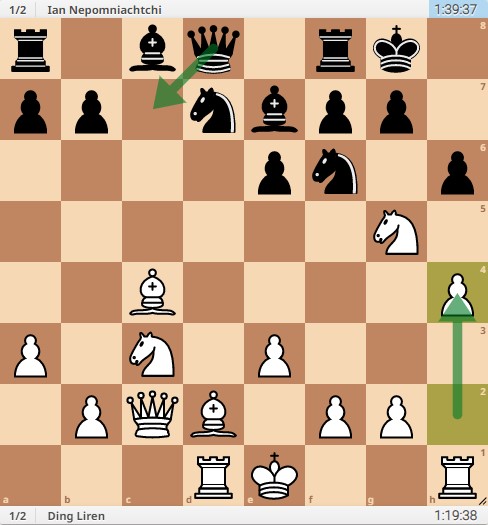

Ding Liren, with the white pieces, returned to 1.c4, and the players gave us a variation of the Four Knights game. The entertaining opening phase was notable for Ian Nepomniachtchi’s ninth and 10th moves. First, he moved his attacked bishop to c5, a move which Ding later said came as a “complete surprise” to him—another example of our man Ding almost always defaulting to the honest truth, even if a little bluff or obfuscation in this scenario might have given Nepo’s team a little less confidence in their ability to find holes in his preparation. And then, after Ding’s queen to g3, protecting his e5-pawn and attacking g7, Nepo chose not to castle, but to play the computer move king to f8!:

This looks crazy, as castling in the opening is usually a must so as to protect one’s king and to connect one’s rooks, but Nepo’s idea (the database shows he previously played this in an online game in 2020) is to protect g7 with his king, thus freeing his rook to stay defending his h-pawn, which will soon be marched down the board.

Ding was out of book, but managed to calculate his way through the complications, and with Black’s kingside pawns rolling, Ding forced a trade of queens on move 18, picking up a pawn in the process. The position remained more or less even despite White’s material advantage, and when one pair of rooks and then the remaining bishops came off on moves 34 and 36, the computer’s evaluation was showing all zeroes.

Nepo found a cute way to arrive at the inevitable endgame draw, starting with pawn to f5:

Here, have my final pawn for free! Disconnecting White’s pawns meant that they wouldn’t be able to coordinate in their quest to get one of them to the final rank, and the White king’s position in front of the h-pawn meant that after the rooks were traded on f5 (eliminating White’s pawn in the process), it would not be able to usher its footsoldier to the promotion square. The resulting position was fit for a beginner’s manual where anything other than suicidal moves would lead to a stalemate with the black king happily straitjacketed on h8.

The game ended in a draw on move 45. It was a fleetingly exciting, but ultimately relatively quiet, draw. Nepo inched a little closer to glory; Ding a little closer to despair.

Game 11

Ian Nepomniachtchi opened up Game 11 again with 1.e4, and Ding stuck to 1…e5, and we had another Spanish Opening. Until White’s 8th move, they followed a game in which Nepo beat Ding in the 2020 Candidates Tournament, which Ding later called “a very bad memory for me”.

Nevertheless, Ding forged into a double-edged middlegame, where the unexpected advance of his underprotected c-pawn created some tension which could have gone wrong for Black in the short-term, but potentially proved advantageous in the long-term. We would never find out, however, as Nepo made the decision on move 19 to snap off that pawn, and shortly thereafter to exchange queens. It was an interesting game, but we don’t need to dwell on it here: the players liquidated into a 3-versus-2 rook endgame, and although Nepo had the extra pawn, a draw was inevitable. The players found a three-fold repetition, resulting in a draw, on move 39.

Nepo had played Game 11 like a pro: he asked some questions of his opponent, and was ready to pounce if a win had looked on the cards, but with a one-game lead and only three games remaining after this one, he made the wise decision to avoid a messy, complicated game, and had shut it down for a draw. Ding would have three more games, including two with the white pieces, to find the win he needed to keep his world title hopes alive.

Game 12

Ding Liren, with the white pieces, again stuck to his trusty 1.d4, and signalled his strategic intentions early in the opening, with the moves pawn to e3? and knight from b1 to d2?:

What in the world? These third and fourth moves by White are known to theory, but were played in less than 0.33% of the 60,000-plus games between masters which reached this position, because there are far better ways to fight for an opening advantage in striking into the center of the board. Ding was clearly trying to get Ian out-of-book early on in this game: forget your prep, Nepo—let’s play chess, you versus me!

Well, they did, and it was Ding who made the first misstep: after a 28-minute think, his bishop takes on f6 covered the board in gasoline and lit a match:

The only response pawn takes on f6 opens up the g-file, echoing the position in Game 2, where Nepo executed a lethal attack on the white king. The computer claims that the position is equal, but I’d probably rather have Black: after knight g3 and pawn to f5, all of Black’s kingside pawns are protecting each other on light squares, with White’s d3-bishop effectively neutralized. Black has retained its bishop pair, while White’s only bishop is weak.

There was still juice in White’s attack, though, and when Ding vaulted forth his g-pawn a few moves later, we had the makings of a slugfest on our hands. Ding’s bishop from d3 to c2? (played after a 13-minute think) was a loose move, essentially wasting a tempo when the position called for action, and after Nepo’s knight to h4, each side had established an outpost on the h-file, where the horses would remain throughout this crucial phase of the game, with no enemy pawns able to shoo them away.

We could diagram pretty much every position throughout this next bonkers stretch: after Ding’s queen to e3 ducking the knight attack, Nepo’s rook to g6! signalled evil intentions down the g-file. Ding responded with rook to g1 (he needed to have played it earlier, instead of that bishop move), and Nepo countered with pawn to f4!, attacking the white queen and keeping the attack rolling, but exposing the g6-rook to attack from the c2-bishop.

After queen e3, queen e7 (setting up the next move), and rook from a1 to e1, Nepo played queen g5! and Ding looked in serious trouble:

Uh-oh: that a8-rook is coming to g8, the two f-pawns will be pushed, the knight is threatening to fork the two rooks on f3 if the queen ever moves, and White will need to hope to somehow survive. Ding decided, after only three minutes’ thought, that he needed some counterplay, and so went for pawn to c4?, attempting to stir up some action on the queenside, a move which got a strong thumbs-down from the engine. Nepo responded correctly, with simply pawn takes pawn, and then met Ding’s queen to c3 (the queen can’t recapture the pawn, because of that knight fork), with pawn to b5!!, a sublimely composed move which ignored the threat of White’s c2-bishop taking the en prise g6-rook, instead protecting Black’s extra pawn and shutting down any initiative White looked to gain on the queenside.

Nepo is winning! This is it! The world chess championship is returning to Russia for the first time since 2007! The computer approves of all of his moves, he’s got plenty of time on the clock, and he’s playing smoothly and confidently, like he does when he’s at his best. He’s about to checkmate Ding Liren with the black pieces and take a two-point lead with only two games remaining. As Nepo sat at the board, he was probably already imagining holding the trophy (is there one? I don’t know) above his head and updating his LinkedIn with “17th world chess champion."

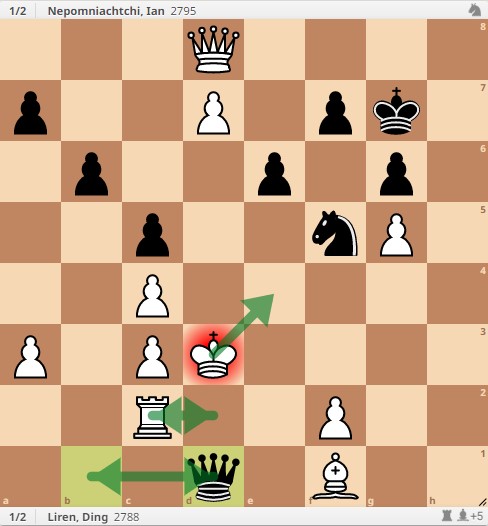

After Ding’s pawn to a4 (trying to split the b- and c-pawns) and Nepo’s correct response pawn to b4, the white queen had no more safe squares along the third rank, and so queen takes on c4 should surely be met by that knight fork:

But no! After only 30 seconds’ thought, Nepo continued with rook from a8 to g8?, his first serious misstep. Why? It looks like he’d been spooked by the response queen to c6, triple-forking the black rook, bishop, and knight. That was understandable, but in fact the knight-fork was actually winning, after a byzantine variation which you’d need to calculate all the way to the end. These recaps aren’t usually for long theoretical lines, but this was such a crucial moment that here it seems worth it: if Nepo went with knight takes rook on e1, then queen takes rook on a8 check, rook comes back from g6 to g8 to defend, queen to e4 (threatening mate on h7 in a battery with the c2-bishop), knight takes bishop on c2, queen takes knight, black queen to h4 (threatening mate on h3), queen d3 defending, pawn to f5 (threatening to take on g4), and after queen to f3, and the players trade pawns, rooks, and queens on g4, it looks like an even endgame, which it would be if not for the astounding pawn to b3!!:

Black can play bishop to a3!! on the next move, defenestrating the bishop in order to queen the pawn! Incredible stuff.

But, Nepo didn’t find that win, and so had played the sub-optimal but still-OK rook from a8 to g8. Ding probably should have played bishop takes rook on g6, but instead opted for queen to c6?!, attacking the bishop and now once again defending from the knight-fork on f3.

And from here, it all started to go wrong for Ian Nepomniachtchi.

Nepo thought for only one minute (when he had 36 minutes for his next 12 moves), on bishop to b8??, a full-on blunder.

Some more thought would have shown that knight to f5! was the move, defending the bishop and vacating the h4-square for the queen (White’s f-pawn can’t take the knight, or the black queen takes the h5-knight). After Nepo’s error, it’s White winning, but Ding returned the favour with queen to b7? (played after five minutes’ thought), instead of taking the g6-rook and following up by pushing the d-pawn, and immediately it was again Black winning!

But don’t worry, Nepo’s not done blundering yet: rook to h6?? again played after only one minute’s thought, threw away most of his initiative, again! Nepo!! What are you doing? Get a hold of yourself, man! Why are you playing so quickly when you’ve got plenty of time? You’re so close to sealing up the world championship! Stop and think!!

Ding correctly responded with bishop to e4, and Nepo finally used some time to think, but spent 10 minutes coming up with another blunder: rook to f8, defending the pawn, was a wasted move, and again it was White who was better! That’s three blunders in a row from Nepo!

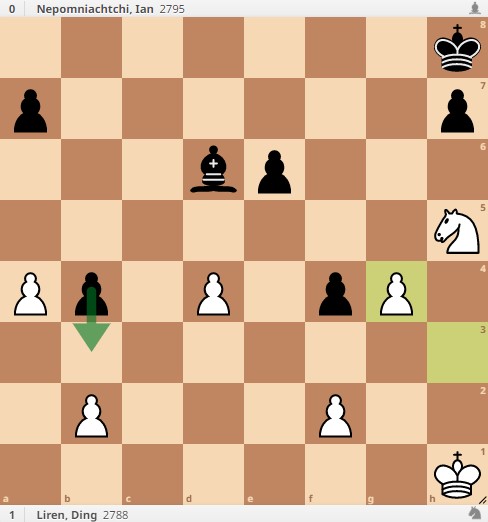

A few moves by each side later, and we come to yet another addition of Guess The Move. In the below position, it’s Ian Nepomniachtchi to move, with the black pieces. After all the above mayhem, the engine says that the position is more or less equal. Nepo has 22 minutes on his clock for his next 7 moves. A win would virtually crown him as world champion, while a draw would still leave him a huge favourite, and a loss would tie the scores, handing the momentum to his opponent. Over to you, reader—what would you play?

The completely inexplicable pawn from f7 to f5??, played after just three minutes’ thought, loses the game on the spot!

What is happening? What on Earth is happening in this match?! Ten minutes ago, the champagne was on ice for Nepo, and in the blink of an eye he’s blundered four freakin’ times and Ding is going to level up the match! I can’t spake! I can’t spake!

It’s genuinely not clear, still, what Ian was thinking here: simply rook takes the now-undefended pawn on e6 (correctly played by Ding in just over one minute), and there’s no good solution that Black can find to prevent White from pushing its pawn to d5, clearing the path for the queen to come to g7 and delivering checkmate. With the f-pawn back on f7, it would defend the e6-pawn, which could respond to White’s pawn to d5 by coming forward to e5, blocking the path to the king (defended by the b8-bishop). There were so many other good options for Nepo: rook to g8, or queen to g5, bolstering the defense of the g7-square and keeping his attacking options open, were fine.

Nepo realized his mistake as soon as he saw Ding’s response, and couldn’t hide his agony: he slumped at the board, utterly heartbroken, for 17 of his remaining 19 minutes, before glumly playing a few more futile moves: rook takes knight on h5 (the only way to kill the immediate mating threat), pawn takes rook, queen takes pawn, and now Ding easily played pawn to d5, check!, king to g8, pawn to d6!, and Nepo resigned, with the white queen, rook, and bishop able to coordinate to harass the black king and queen the d-pawn. It happened just like that!

Oh my God. Excruciating. Nepo had come so close to the world champion title that he could taste it. He was probably rehearsing his victory speech, making sure he wouldn’t forget anyone important. Instead, fortune shined on Ding Liren, and he miraculously levelled the scores with two regular games to go. We should give the winner some credit—Ding fought through an incredibly complicated worse position, found a way to muddy the waters, and found a way to not be the one to make the final blunder—but the story of this game was Nepo’s collapse. He cut a predictably forlorn figure at the press conference; a beaten man who fully realized how close he’d come to achieving his lifelong dream. For the second time in this match and the fifth time in his world championship career, he’d blundered the house in one move, and he’d once again have to find a way to turn things around.

Game 13

In Game 13, Ian Nepomniachtchi had his last try with the white pieces in the classical portion of this match. He again opened up with 1.e4, Ding Liren replied with e5, and we had another Spanish Opening.

Ding appeared to have a better position into the middlegame, making more efficient moves despite Nepo not really putting an identifiable foot wrong. A crucial moment came on move 21:

Ding’s rook to e5?! was a move so odd it was hard to explain. The e4-bishop’s line of sight through the knight to the undefended bishop and to the rook needed addressing, and rook to b8 looked the best try, with the rook eyeballing the b2-pawn. Or, even more directly, queen g5 was an attacking option, with White needing to prevent the follow-up knight to f4, threatening mate or huge material losses. Instead, as Ding explained at the post-game press conference, the rook move was a funky way of defending the d5-knight, as he expected Nepo to take the knight on his next move (though he did not).

Ding traded that rook for the e4-bishop just a few moves later, and after the queens were exchanged off the board, the players had an unbalanced and complex late-middlegame/early endgame. It was an interesting struggle, but with so much else going on in this half of the match, we won’t focus on it too much longer: the players shook hands for a draw on move 40.

Heading into the final classical game, it was a contrast in attitudes at the press conference: Ding looked in fine fettle, happily talking about the game and seemingly excited for Game 14, while Nepo (understandably) stonewalled and looked like he wanted to get out of there as soon as possible. How would they fare in the final game?

Game 14

Ding Liren had the white pieces in the final classical game, and, as in Game 8, after 1.d4 we got ourselves a nice Nimzo-Indian game.

Ding soon showed that he was ready for a fight, and instead of playing for a calm position with little risk, he decided to blow the doors off the joint with a similar motif to what we saw in Game 8: knight to g5?!, pawn to h6, and pawn to h4?!

Now it’s a knight on g5 instead of a bishop as in Game 8, but the threat is the same: if pawn takes knight, pawn takes pawn wins for White, as Black must defend from checkmate on h7 rather than protect its f6-knight, and the king’s defensive pawn structure will be fatally compromised. However, Nepo’s response queen to c7 was universally praised: it coolly ignores the White attack, threatens the c4-bishop, and X-rays the undefended White queen.

Even as that initial attack went nowhere, Ding seemed always on the hunt for aggressive play, and arranged a rook battery on the g-file toward Nepo’s king, but it was never likely to have enough juice. White’s misallocation of resources compared unfavorably to Black’s harmonized pieces, and after White’s careless king to e2? (leaving the c3 square unguarded), Nepo played rook to c3! And the win was all sewn up:

This is huge trouble for Ding: both rooks are attacking the d3-bishop, and it can’t move, or else bishop takes b5 check would be deadly. One rook can swing up and over to defend d3, but an exchange on that square will just be met by the same bishop b5 move, pinning and winning. Material losses are inevitable, and Nepo will have a swarming control over the center of the board, ready to pick off pawns at will and march his a-pawn to a1.

This is it, surely! It’s over, folks, Ian Nepomniachtchi has got a crushing position, and is winning the big one this time. With the black pieces in the final classical game, no less! What a story. A few more composed moves and Ding will offer a handshake, and Nepo’s comeback story will be complete.

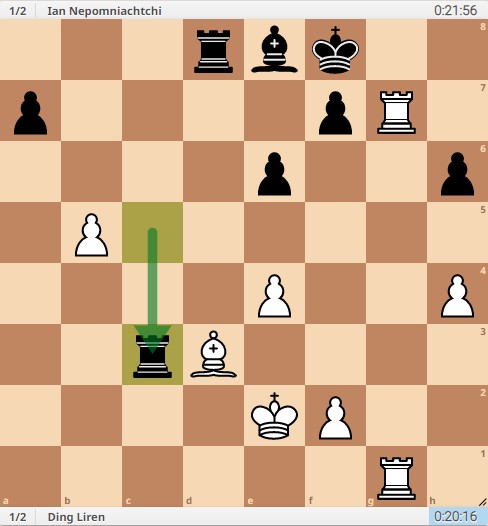

But nyet! After rook g8 check, king to e7, and rook from g1 to g3, somehow the perfectly natural-looking pawn to e5?? throws away all of the advantage! What??

How? After rook to h8 (threatening to double rooks on the eighth rank) and rook d6, White has the save pawn to b6!, when after rook takes on b6, rook takes bishop on e8 check!, the king recaptures, and bishop to b5 check! (it was the push of the b-pawn that freed that square and made this move possible) sacrifices the bishop but picks up the undefended c3 rook! Ding had found a combination to sacrifice a pawn in order to avert the immediate danger, and suddenly, it’s a rook endgame where Nepo had an extra pawn but no longer had anything close to a decisive advantage. What a cruel, cruel game!

Nepo must have felt sick while playing the endgame, knowing that he once again fumbled the bag when the hard work appeared over. He had an outside passed pawn in the endgame, and so could press for a win, with the defense by no means trivial for Ding, but he must have known in his bones that he blew his best shot. There were several critical junctures along the way where the game could once again have turned in Nepo’s favor, but ultimately Ding did manage to trade three pairs of pawns, and finally the rooks, and the game ended in a draw on move 90.

What a finish. Ding had made an exhilarating save, and Nepo had once again had the football snatched away just as he was about to kick it.

And so, for the third time in the last four world championship matches, we’re headed to tiebreaks. It had been a bonkers match full of ups and downs to this point, and absolutely anything could happen. The only certainty was that it would end not with a whimper, but with a bang.

Tiebreaks Games 1-3

If the world chess championship is tied after the classical portion of 14 games—they need to play an equal number of games with each color, since the player with white pieces always moves first and therefore has an advantage—the players play a series of games at shorter time controls to determine a champion. It’s not a perfect system, since short-format chess is a different beast to classical: it would be like settling a tie in the Olympic marathon by having the competitors face off over 5,000 meters (and, if they tie in that race, over 1,500 meters and eventually 100 meters). It’s not easy to find a better solution, however: the 1984 world championship match between Anatoly Karpov and Garry Kasparov was a first-to-six-wins affair, and was controversially abandoned after 48 classical games over five months with Karpov leading 5-3.

We’re going to zip over Games 1-3 of the tiebreak, folks, since this recap is already long enough, but just know that there was some good chess played. In Game 1, in a tense middlegame where Ding looked to be better with a monster knight on d6, Nepo offered to sacrifice his queen (!) in a thirsty counter-mating attack. Ding saw the danger, however, and chose instead to steer into an even endgame, with the players finding a repetition for a draw on move 35. In Game 2, a bog-standard RuyLopez gave us some lively moments, but ultimately led to another even rook-and-knight endgame, with a draw reached on move 47. In Game 3, Ding couldn’t get any play out of a King’s Indian Attack opening, and queens were traded early as the players reached an opposite-colored bishop endgame, and found a draw on move 33.

Tiebreaks Game 4

Ian Nepomniachtchi had the white pieces in the final rapid game, where the players started with 25 minutes on their clocks, and would receive 10 extra seconds with each move played. A decisive result would crown the winner as world champion, while a draw would mean that the players would move to a series of 5-minutes-plus-three-seconds-per-move blitz games.

The players repeated the first 11 moves of their Game 2 tiebreaker in a line of the Ruy Lopez (or Spanish) Opening, in a variation where Nepo for some reason stuck his light-squared bishop on b1, out of play behind a wall of connected pawns.

The first critical moment of the middlegame came on move 29, when Ding strayed with pawn to e4?:

Black’s queen and bishop battery are staring down the White kingside, but this pawn break was too hasty: pawn takes pawn on e4! was an easy option which breathed life into White’s b1-bishop. After the intermezzo knight to e5 and queen to g2, knight to d3 invited simplification, as White could simply trade its bad bishop for the good knight, and after capturing on f5 and a trade of rooks, White was better, with an extra pawn (temporarily, at least). Crucially, Nepo had 12 minutes to Ding’s six—a huge buffer, particularly given Ding’s time-related meltdowns in Games 2 and 7 of the match.

The position was double-edged, and although the engine claimed it was close to even, Nepo had the easier and more dangerous play, with a safer king and more mobile queen and rook, before even taking into account advantage on the clock. On move 40, Nepo’s queen invaded Ding’s first rank and harassed his rook; on move 41 Nepo’s queen invaded Ding’s eighth rank and harassed his queen. It was Nepo pressing and Ding reacting, with the time ticking toward zero. Would this be it? I think this is it! Ding has no time! Nepo’s position isn’t overwhelming just yet, but everything is pointing to him taking the win: he can make far more natural moves and create more complications for his opponent, and Ding’s dwindling time will cause him to have to make hasty moves, surely leading to a fatal error.

But in a heart-in-mouth sequence, Ding fought back hard, and after some accurate defending it looked like Nepo’s attack wouldn’t have enough juice. He prodded and probed for a dozen moves, looking for a way in, but it looked like Ding had calculated well enough to find a fortress, enabling him to play quickly enough to preserve his time! What a save!

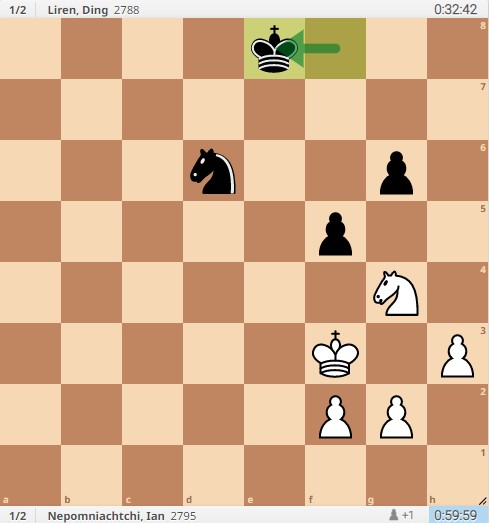

Nepo accepted that the opportunity for a win had passed, and on move 44 in the below position, starting with Nepo’s queen to e4 check, the players had found a repetition of moves, meaning that the game would end in a draw. Ding moved his king to g8, and then after queen to d5 check, and king back to h7, Nepo played queen to e4 check to repeat the pattern. Ding had yet again made an escape, and would surely be counting his lucky stars he’d managed to survive. With the adrenaline surging, the players can now take a breather, and Ding would be thankful to accept a draw here after coming so close to losing, and the match is going to blitz tiebreaks, he’d obviously repeat with king to g- BAH GAWD DING PLAYED ROOK TO G6:

This is one of the coldest things I’ve ever seen. It made me involuntarily yelp Whaaat?! out loud in the crowded coffee shop where I was following the game. The absolute stones on this guy. My God.

Ding doesn’t care that he’s just stared down the barrel of a fatal loss and found an escape in the most important game of his life; he doesn’t care that he’s perilously low on time; he doesn’t care that this continuation is risky, self-pinning his rook and inviting the h-pawn to come and capture it—he’s evaluated that his passed pawns give him a chance to win this game, and he’s going for it, consequences be damned. He’s saying to Nepo: When you dance with the devil, you wait for the song to stop. I’m not stuck in here with you; you’re stuck in here with me. I’m ready to be world champion.

Nepo had 4:24 on his clock to Ding’s 1:33 before the above sequence, and took about one minute both times he played queen to e4. I think Nepo assumed that Ding would acquiesce to a draw, and so carelessly spent more time than he needed in performing some last-minute calculations of other possible variations rather than committing to repetition. When Ding flipped the script, Nepo had to switch back into defensive mode, and maybe panicked because of the fact that he’d frittered away half of his clock time so needlessly.

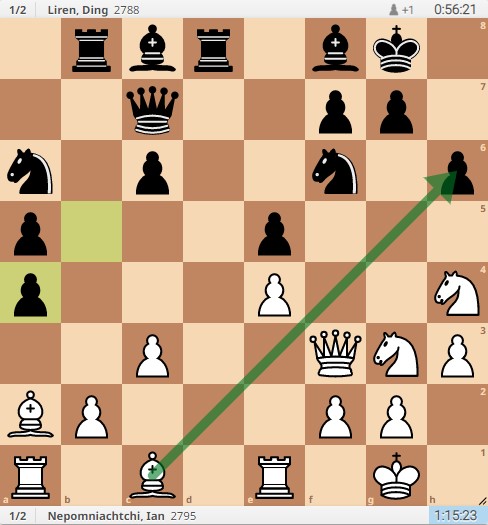

With the game back on, Nepo (perhaps flustered by the unexpected turn of events) rushed and immediately erred with queen to f5, when pawn to h4, threatening to push it one more square and win the rook (it’s pinned to the king and can’t move), was the correct continuation. Ding played his strongest card by pushing his pawn to c4!, and now Nepo’s pawn to h4?? was one move too late and a blunder! Queen to d3!! and the black queen is attacking the white queen and defending the g6-rook (she couldn’t do that a move earlier, because with the pawn back on c5 the queen would be undefended on d3), and helping usher the c-pawn to the eighth rank. Just like that, out of absolutely nowhere, with a couple of loose moves from White, Black’s two passed pawns were overwhelmingly powerful, and the position had gone from drawn to winning for Black!

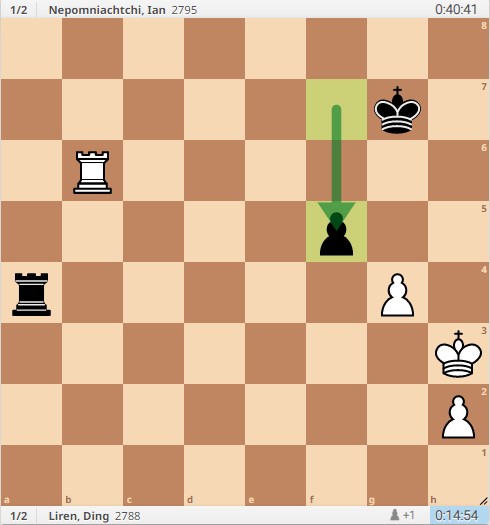

Ding managed to engineer a trade of rooks, and his two passed pawns were rolling. It will go down as a historical curiosity that in the postgame analysis the computers show that Nepo apparently had an insane perpetual check on move 59, where he could have sacrificed his bishop on g7 and proceeded to harass the Black king from the light squares in the center of the board. It was impossible to find in a rapid game with 27 seconds on the clock, however, and wasn’t a “true” missed save.

Ding continued to consolidate his position and coordinate his pieces so as to march his pawns to promotion, and the final sequence started with Nepo’s loose king to f1:

That’s not ideal, as now one of Ding’s pawns could queen with check, and Ding went in for the kill: bishop to e5!, protecting the a1 promotion square and creating the option of bishop to b2, also guarding c1. Nepo tried to throw something at the wall and see if it would stick: pawn to g4?, did nothing after pawn takes on g4, and pawn to h5 was just as effective after simply queen to f5, when the queen is now staring directly at the king. White’s queen to d5 pinned Black’s bishop, but couldn’t stop pawn to g3!, and after pawn to f4, the killer pawn to a2!!, and Black has to choose between letting that pawn promote, or having the queen abandoning the king’s defense to capture it. Here, Nepo lost his poker face: he turned away from the board and stared off into the distance as his time ticked down, he reached out to grab one of the already-captured pieces sitting beside the board and accidentally knocked them all over, and looked a man utterly crushed. He composed himself enough to play queen takes a2, but after Ding’s bishop takes pawn on f4, Nepo extended his hand to resign, and Ding Liren was the 17th world chess champion.

Pandemonium! A fittingly thrilling finish to a thrilling match. It couldn’t have ended any other way. The image of Ding sitting at the board with his head in his hands, crying with joy at having realized his dream, will live on in chess immortality.

“Quite relieved” was how Ding described his emotions at the postgame press conference, as he had definitively proved that he believed he was worthy of being the world champion. You’ve gotta love the guy: he thanked his friends, his mother, and his grandfather, and said that he wants to now do some travelling, including to Turin to see a Juventus game. Nepo’s assessment, “I guess I had every chance,” was downright heartbreaking in its truth, as he came as close as it’s possible to becoming world champion without doing so, in becoming the fifth two-time challenger to never hold the undisputed title. Nepo should hold his head high, as he played at an incredibly high level throughout the tournament, but the winner-takes-all nature of the match means that he will be left rueing a series of key moments which could have changed everything.

And so, chess enters the Ding Liren Era. His reign will presumably further popularize chess in his home country: while China already has four of the world’s top 30 and the women’s world champion, our game competes with Xiangqi (or “Chinese chess”), a superficially similar board game which relies more heavily on pure calculation. In addition, I’d imagine that Ding will become an even more dominant force at the board, as the self-confidence that must come with the world champion title will spur him to even higher heights.

In a match that was so acutely defined by what was happening between the players’ ears as much as by the action on the board, we were treated to a fitting ending. Cometh the hour, cometh the man: in deciding to push for a win starting with the move heard ‘round the world, rook g6, Ding dared to be great. He showed that he had world champion-level mettle, and was rewarded on the board. At the start of the match, his nerves caused his hands to shake; by the end of the match, his nerve earned him a victorious handshake.

We’ve got a new world chess champion, folks. The king is dead. Long live the king.