Every March, I get an email from Joan Lanigan at City Hall: The Binder has arrived.

The Spelling Bee words are in The Binder. I need The Binder because I'm the Pronouncer.

And so, my annual participation in the Boston Citywide Spelling Bee begins with a bit of spycraft—not the Tom-Cruise-scales-the-Burj-Khalifa type, more the George-Smiley-hands-you-a-file kind.

The handoff always takes place somewhere on my campus in between classes. Over the years, Joan has popped out of the passenger seat of an illegally parked car to hand me the nondescript white three-ring binder. She has waited for me in the rain, under an umbrella, outside my classroom building. She’s shown up in sunglasses and workout clothes, dropping The Binder off before her run. This year we met on the steps of the Museum of Fine Arts.

Joan's not paranoid. She just does things by the book. As Program Manager at the Boston Centers for Youth and Families, Joan is the city's point of contact between the Scripps National Spelling Bee and the several dozen public and private schools in Boston who send representatives to the regional competition. The winner of that competition receives a trophy, various wordy prizes, and travel and accommodations to the National Spelling Bee, just outside of Washington, D.C., where they'll have their words pronounced by Dr. Jacques Bailly, the affable, unflappable LeBron James of the Bee world.

The Scripps people do not provide the word list digitally, because they want to limit sharing. It says so at the top of the first page, centered in red italics:

"Please do not give this guide to any spellers, parents or teachers.

The Scripps National Spelling Bee will provide your regional champion with study materials for the National Competition."

This is the Spelling Bee. OpSec is critical.

I own a physical dictionary that I don't use (I have institutional access to the OED online, so). It's bright red, the title embossed in gold letters: Webster's New World Dictionary: Third College Edition. A typed mailing label affixed to the inside cover lets the curious know how it was acquired:

LAFAYETTE COUNTY LUTHERAN

SPELLING BEE CHAMPION

GRADES 7 & 8 1992

I'm not trying to write another verse to "Glory Days" here, but I dominated that competition. Knew enough to ask for a definition of guerrilla to make sure I didn't start "G-O-R," on the final word. It was not even a thing.

With that victory, I rode a wave of supreme confidence into my own Regional Competition in Warrensburg, Missouri. I didn't think D.C. was in the bag, exactly, but I felt pretty good as I stepped up to the mic and hesitated only briefly before spelling my first word, a warmup: "KNITWARE. K-N-I-T-W-A-R-E. KNITWARE."

Ding!

The echo lingered in my ears as tears of shock formed, stinging, behind my eyes. Knitwear. It's something you wear, of course!

I'm over it. "KNITWARE" does not appear in my Webster's, or in the current OED—though it does seem to be in use on knitting sites like Ravelry and on Pinterest and other places, where practitioners of the art are using the word, and don't most dictionaries see their jobs as descriptivist rather than prescriptivists, so maybe I was really just ahead of my time?

Like I say, I'm over it.

I tell this story to show why I take my present job seriously. I am one of the last lines of defense between a speller and lifelong trauma. As a neighbor of mine helpfully observed, "When they get it wrong, yours is the face they're going to remember forever."

So, after I get The Binder home, I'll flip through it over several nights, looking for tricky or unfamiliar words: jimberjawed, pandiculation, bruxism, jibboom, costumbrista.

The Regional Competition list comprises 500 words. Words 1–350 are selected from "Words of the Champions," the 4,000-word study list Scripps offers to Bee affiliates or the Bee-curious. The remaining 150, if we haven't yet decided a champion, are selected from Webster's Unabridged. In my four years at the Boston Bee, we've never gotten that far.

Each of the 500 entries includes a phonetic pronunciation, a definition, the part of speech, a note on its language of origin, and its representative use in a sentence. The spellers are allowed to ask for any of this information. The real contenders usually ask for all of it.

It's good to re-familiarize myself with Webster's house style for its pronunciation marks; some marks can sneak up on you at inopportune times. Even words that I take for granted can cause me to look twice. I'm confident I know how to pronounce editorial, but if I glance at the pronunciation guide I see \ₗedəˡtōrēəl\. It takes a minute to re-familiarize yourself with the conventions after a year away.

The morning of this year's Bee, I hopped on the Red Line to head to the Boston Public Library and pulled out my phone to read up on the hockey season. I don't follow the NHL closely and I need to get up to speed, because the man to my left, the Records Judge, is supposed to again be Dave Silk, former right wing for both the Bruins and U.S. Hockey's 1980 Miracle on Ice team.

My qualification is that I'm an English professor at a local university. Dave jokes that his qualification is that a newspaper story once reported he was the only member of the New York Rangers with a library card. Really, though, he's there as a representative of the Boston Bruins Foundation, the event's presenting sponsor.

The Records Judge maintains a stack of cards. Each one has the speller's name and number, plus blank lines for each round of the competition. The Records Judge calls the speller to the mic, then writes down—in pencil—each letter as the speller gives it. (Spellers are allowed to start over and spell the whole word again, but they are not allowed to alter any letters they've already spoken).

It turns out my reading up on the Brad Marchand trade was for naught: Dave was unable to make it at the last minute, and a staffer from the BCYF has to fill in.

I'll miss Dave, with whom I've enjoyed scouting spellers over the years. During breaks in action, we'd discuss who from among our motley, hormonally imbalanced crew had a realistic shot. It's always clear that some kids are there to win, and some are in over their heads. But you can't tell by looking. This is what happens when you take a relatively random sampling of 10–14 year-olds. Height is meaningless. So is facial hair.

A couple of years ago, Dave and I were both very high very early on Tanoshi Inomata, a then-fourth-grader with ice in his veins. He sprouted a long ponytail and wore a snappy blazer and a piano-key bowtie, but that was the extent to which he let his personality show. Expressionless, he'd approach the mic, hear the word, ask for all of the information, spell the word, and wait for confirmation that he'd nailed it. Just as expressionless, he'd return to his seat. He took the trophy two years in a row. Never saw him smile.

Tanoshi's not here this year, either, so I'll have to find a new favorite while breaking in yet another new Head Judge. The Head Judge has the best title but the worst job. After the speller makes the attempt, the Head Judge either says "That's correct," or dings the bell to signal an error, at which point I read out the correct spelling.

It's a thankless job, which is my theory as to why we've gone through four Head Judges in four years, from the President of the Boston Public Library, to various mayor's office officials, to this year's Deputy Chief of Staff of Boston Public Schools. To each of my Head Judges: You were great, and I get why you don't want to come back. There's not a lot of action, and when there is you have to be the bad guy.

We're finally ready. The Binder assures me that which words we select to be spelled are up to the judges' discretion (that's us!): "You don't need to start at the beginning of a word list, and you don't need to go word for word through the list." We can jump forward if we think the words seem too easy. Or jump backward if we've started in a too-hard section. Throughout the list appears a periodic box with the italicized reminder: "There is no rule stating that you must proceed word-for-word. … You may skip a word if you sense that the word may present a problem at your bee."

I like to begin at the beginning, let everyone settle in. We're cruising out of the gate: onion, sword, gargle, broil. By Speller 15, I'm wondering if I have, in fact, started off too easily: abolish, ballad, amass, homesteader. If I have, there's nothing I can do until everyone's had one turn. I'm not going to skip ahead in the middle of a round.

And then, Speller 18 trips up on dawdle. The day's first ding brings a mix of emotions: sorrow for the speller who sat down first, along with the guilty relief that at least we won't be here all day.

Then three out of four spellers go out, on modem, buffet, and tawny. We lose two more on casserole (one s, no terminal e) and squabble (dropped a b). By the middle of Round 2, I'm worried we'll be done before lunch.

Every so often, ahead of a word, The Binder instructs me to "Say to the speller: 'This word has a homonym or could be confused with another word.' Say the word and provide the word's part of speech and definition." For instance, wince: A bracketed note in the entry helpfully suggests, "Could be confused with wins." Had the speller said "wins" back to me, and if I'd heard it as "wince," and they didn't ask for a definition, the poor kid would be dinged out having correctly spelled the word they thought they had. Phew!

Sometimes it seems like overkill: You get the homonym-or-could-be-confused note on carriage, "a horse-drawn vehicle designed for private use and for comfort or elegance." The Scripps/Merriam-Webster folks suggest the word "Could be confused with carritch," which, as I know you know, is a Scottish word for "catechism." In any case, the spellers carried off wince and carriage without flinching.

We weren't so lucky on kernel, another homonym. I did as instructed: "Kernel, noun, a central or essential part."

"Like the military?"

I couldn’t answer his question directly, yet I knew the speller wasn't on the right track.

"Would you like me to use it in a sentence?"

"Yes, please."

"A sense of wonder is the kernel around which a good education is built."

I could tell he still didn't have it. Agonizing. He simply didn't know the word being asked. But he knew how to spell "colonel," which is what he offered.

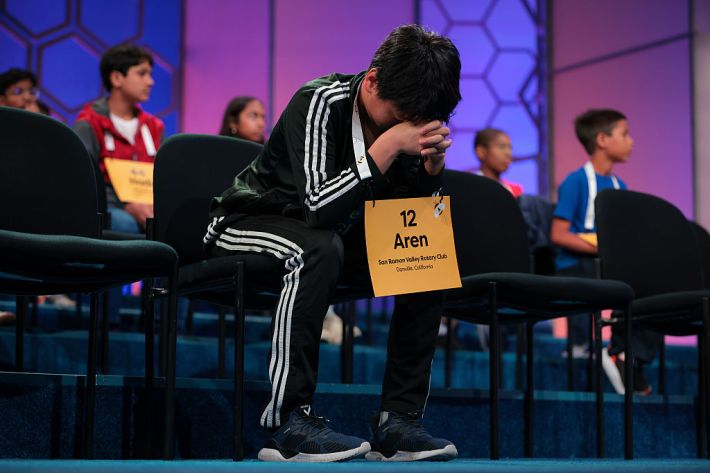

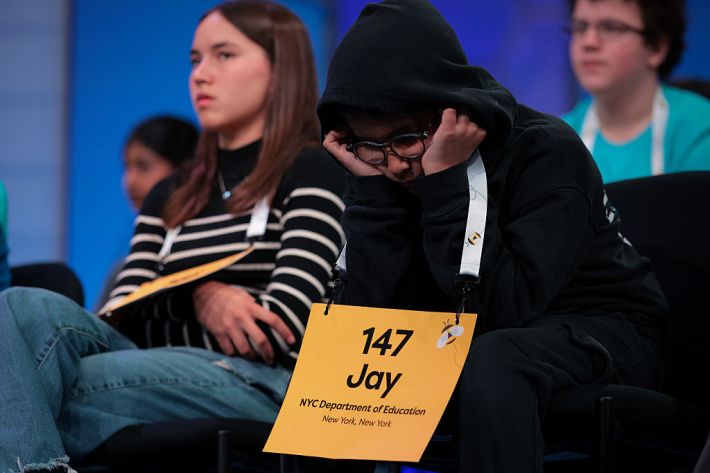

A somber ding.

I don't have the face for poker, so it's a relief that most of the time the spellers aren't looking at me as they try to conjure their word. Their gaze is focused somewhere at the back of the auditorium, or their eyes are screwed up tight as they use an index finger to trace out letters on the palm of their hand.

I make eye contact only as I wait for confirmation that they have the right word and to see if they request any more information. (Even if they don't start out doing so, most of the spellers who survive into the later rounds catch on, and by the final three or four everyone asks for "all the information" every time.) Otherwise, I'm staring into The Binder, eyes fixed on the word, willing the speller to get the next letter right as I try to keep my expression perfectly neutral.

The tensest moments can occur during correctly spelled words. One speller took what felt like about two minutes to successfully complete partridge, while I held my breath during the 30 seconds another speller took between the C and the H in mischief.

I am rooting for each speller. I want each of them to spell every word right. I want to be there all day. What I want even more than that, though—much, much, much more than that—is for no one to misspell a word due to a mistake I made.

Take frisket, which as I know you know is a noun from Germanic-derived French meaning "a sheet stretched in a frame with parts cut out to lay over an inked form so that only certain parts shall be printed."

I said, "Frisket."

The speller said, "Friscant."

I interjected immediately, "Frisket." Channelling my inner Dr. Jacques Bailly, trying to make that final "-et" as sharp as possible.

The speller said, "Friscant."

I said, "Frisket."

We went through all the information, including its use in a sentence.

He spelled: "F-R-I-S-C-A-N-T."

After the ding, and during my ritualized offering of the correct spelling, he let out an agonized "Nooooo," realizing, presumably, the way he'd misheard it.

That sucked for both of us.

Judges also need to be able to hear clearly. At another point two of us at the table heard a "T" where the "D" should be in pedigree. The other one wasn't sure. After some murmuration, the Head Judge dinged the bell.

There was an uproar from a good chunk of the crowd.

I spelled P-E-D-I-G-R-E-E into the microphone.

"That's what she said!" someone yelled.

I turned to Joan Lanigan, who was thankfully sitting right behind the judges' table, "We heard 'T.'"

"She said 'D,'" Joan said, with a confident nod.

The Judges' decisions are final—including the ones, like pedigree, where we unring the bell and reinstate the speller.

The fourth-place speller went out on onus. Afterward I was accosted by an aggrieved parent unhappy about the definition we gave. She thought that "Something distasteful or objectionable and difficult to bear" was too Snowflakey for onus.

"Onus is a responsibility, and this is not a bad thing, responsibility is good," she said, brandishing her phone with a Google search result which did offer a more neutral definition. She was arguing not on behalf of her kid—who had finished as the runner-up—but the principle, I guess.

I actually thought she had a point. There may in fact have been a shift in the language which now makes the Merriam-Webster definition seem to have a slightly more negative shading than current usage would dictate. But definitions change! Spellings change! One of Noah Webster's whole things was divesting American spelling of its Briticisms. Some of it worked. Some of it didn't.

The point I was too tired to make at the time was this: To hold a competition as fun and great and indirectly educational as this, you have to draw the line somewhere. Winning the Spelling Bee means you have a good handle on a large subset of words and their current usage and spelling; it doesn't mean you have mastered the language.

Even as you're winning, the language is changing underneath you. That's the fun part. We're going to get "knitware" in the dictionary.

We were down to three. Everyone on stage would finish with hardware. That takes the sting out. A little.

One of the three, I had been slow to realize, was Sapna Malhotra, who'd finished as Tanoshi's runner-up the year before. I remembered her as the girl who responded "Thank you," every time the Head Judge said "That's correct." I'd noticed her doing it on deceitful back in Round 6.

After two rounds of perfect spelling—cacao, vengeance, epidural—I decided we should skip ahead. We were only on Word 134, and it seemed like these three could keep it up awhile.

It's not fair for me to choose a word for the speller leading off the round. So I chose a number, and started reading from there: compendium, mortician, polyester—two more rounds of perfect spelling. Let's go to 200. At the end of Round 16, lacustrine reduced us to two. I turned the page to give the final duo a fresh start. The first speller missed crinoline; Sapna got bannock.

All she had to do now was spell one more word correctly, during the championship round. I chose word number 250, sight unseen. It turned out to be senecio (the definition is long: it's a plant). Sapna nailed it.

She said "Thank you," again, but this time she said "Thank you, Mom! Thank you, Dad!"

In the photo-op aftermath, Sapna's mom approached to tell me her daughter "remembered you told her last year, 'You'll be back.'" My Bee handicapping chops are as solid as ever.