The thing that the New York Yankees are doing is not sign stealing. For one thing, it is entirely independent of the communications of their opponents, which raises it entirely above the board, according to both the rules and the traditions of baseball. For another, professional baseball no longer has signs for the swiping. A team could theoretically hack the PitchCom—the Houston Astros probably have a whole secured campus of evil nerds working on this opportunity—but until someone finally figures out how to bug one of those little suckers, it will remain impossible to intercept and decode the signals between a catcher and a pitcher.

Sign stealing, among fans, was always considered a touchy, somewhat gray area of gamesmanship. Still, what the Yankees are doing would be considered at the honorable end of things even if it did involve decoding signals. They aren't being subtle about it at all: The guy on second base communicating the pitch selection to his teammate in the batter's box is doing everything short of holding up a gigantic poster. Against the Seattle Mariners, back on July 10, Trent Grisham and Cody Bellinger were gesturing so blatantly during New York's late comeback that a baseball non-knower might reasonably have deduced that they were doing aerobics out there. It was a delightfully elaborate system: First, the runner on first base had to peek into the glove of Mariners reliever Andrés Muñoz and spot his grip, in the seconds before the pitch was thrown. They were on the lookout for sliders; when Muñoz's slider grip was identified, the runner on first had to then give a clear hand signal to the runner on second base, whose job was to relay this signal to the batter, in many cases as Muñoz was delivering the pitch. In order to pull it off, Grisham and then Bellinger resorted to what I think we can describe as an "inflated tube man" gesture, designed to be unmistakable for a batter whose attention is directed elsewhere.

"Obviously, they weren’t making it very discreet, I guess is the word," recalled Mariners catcher Cal Raleigh, who admitted that Muñoz was tipping his pitches by providing a view into his glove. "It’s part of the game. It’s our job. We should have known about that going into the series."

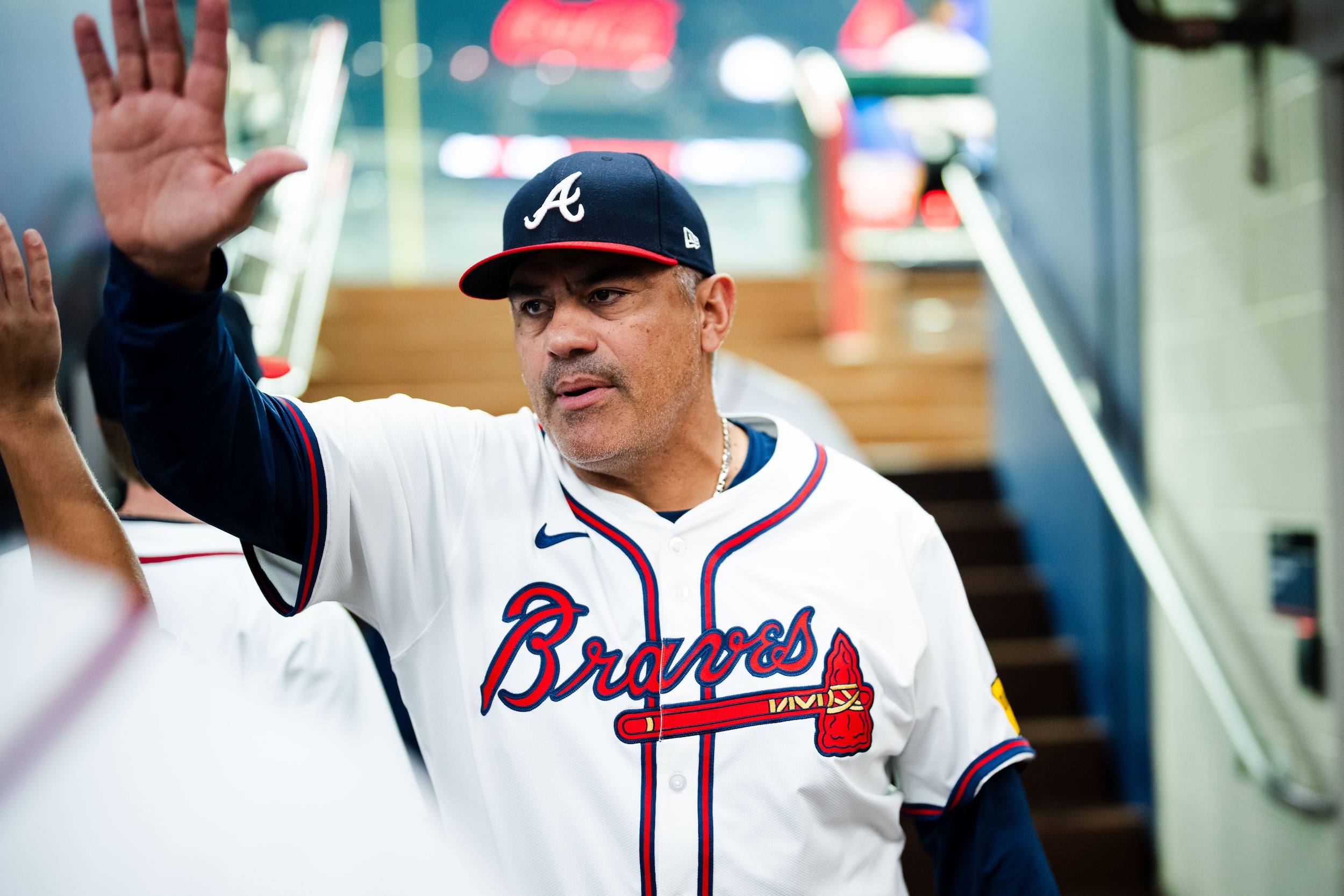

So the Yankees are known around baseball this season for hunting this particular edge, in their particularly dopey way. This was evidently on the mind of Braves lifer Eddie Pérez during Saturday's game in Atlanta. In the sixth inning of what was an eventual 12–9 comeback win for the visitors, Yankees second baseman Jazz Chisholm Jr. drilled an RBI single to right field and then advanced to second a batter later on Matt Olson's fielding error. While on second, Chisholm did a lot of moving, a lot of very animated bouncing and gesticulating, including what looked like the "inflated tube man," enough to draw the eye of a viewer, and certainly more than enough to draw the attention of a suspicious assistant coach.

The Yankees were all over Atlanta's relievers that inning: Enyel De Los Santos failed to record an out against the first four batters of the frame, and the Yankees drove in runs in three straight at-bats against Rafael Montero. Chisholm made it to third on Anthony Volpe's drive to the warning track in center field, and that is when he and Pérez exchanged glances and then words and gestures. Pérez appeared to be scolding Chisholm for his antics on second base, and Chisholm at first responded to Pérez by doing the little "boo-hoo" crying hands. When Pérez continued, Chisholm alternated between a shooing gesture and then a beckoning gesture, evidently unsure whether he wanted Pérez to leave his sight or to stand before him and answer for his crimes. It was somewhere in here that Pérez gestured to his own head, in a way that Chisholm interpreted as a threat of retaliation.

I am going to interrupt this rundown to highlight a humorous incident from Pérez's history in baseball. Back in 2014, when Pérez was on the staff of then-Braves manager Fredi Gonzalez, Atlanta pitcher Aaron Harang became concerned that the Miami Marlins might be stealing signs, something that was still possible back then. A week earlier, Harang had dominated the Marlins, but on this day they were pounding him into the turf like a garden stake, and he felt bad about it. "It was baffling, like, where were these guys last week? They were way too comfortable," Harang said after the loss. "It seemed like they were all hitting like Ted Williams." The Braves, flummoxed, lost their cools: By "the early innings," recalled Gonzalez, the team's dugout had slipped into a condition of distracting paranoia.

"We got three guys looking at the scoreboard. You got two guys looking at their bullpen. I'm calling Eddie, 'Eddie, do you see anything?'" The Braves changed signs five times during Harang's disastrous four innings of work, and were using complicated multi-step signals even with the bases empty. At one point, he and his coaches began even to suspect that the hideous and since-removed statue in center field at Marlins Park was some sort of sign-stealing device. They began picking out and suspecting individual fans in the stands. "There was one guy sitting out there who had a red hat and an orange shirt," said a laughing, somewhat sheepish Gonzalez. "I said, 'Boy, that's a bad combination to have.' I told [Jordan] Schafer and [Tyler] Pastornicky to keep an eye on that guy over there. The guy got up, went to get a Coke."

Maybe Pérez never recovered from this episode! Maybe the longtime personal catcher of Greg Maddux, perhaps history's greatest pitching tactician, has particularly strong feelings about pitch-tipping, as a gently but inarguably underhanded way of getting the better of a hurler. At any rate, while everyone else with the Braves was being reasonably chill about New York's sudden onslaught, Pérez was over there making ill-advised skullward gestures to an opposing player, in a sport where code violations have at times been punished with beanballs. Chisholm did not enjoy this part.

Asked about it later, Pérez insisted that the gesture was not meant as a threat. "I just wanted him to be smart, that’s all it was," Pérez told The Athletic. "Use his head. I have a lot of respect for that guy, I like him, but I guess he didn’t like what I had to say and got upset with me. It wasn’t threatening. I just wanted him to play smart out there."

Yankees manager Aaron Boone was pretty upfront about the whole signaling thing. "You’re trying to find little advantages out there, you’re trying to find little ways to 'help you win a ballgame," explained Boone, who says every team is doing it. "So that’s all within the parameters of the rules." When asked about Pérez's gesture and whether he interpreted it as a threat, Boone said he hoped Pérez "didn't mean anything like that by it," but also said it would "deserve some looking into." Later Sunday, The Athletic reported that Major League Baseball is, in fact, investigating Pérez's gesture.

There are lessons here for everyone. Everyone needs to work on their gestures. If the Yankees want to continue to pull advantages from decoding or otherwise revealing the pitch selections of their opponents—or, along those same lines, if they do not want to be reviled by their peers—they should do better than waving their arms around like crazy people. If the Braves do not want to be made vulnerable by what outsiders can interpret from finger positioning, they should work a little more determinedly on obscuring their intentions. That wisdom applies to both flustered relievers and red-assed assistant coaches, in equal measure.