Dante Alighieri thought he could write himself out of exile. In 1300, while serving on a governing committee in his beloved Florence, the poet was involved in a factional dispute among city leaders. The following year, while in Rome on a diplomatic mission, he found his own faction on the outs, was charged with corruption, and sentenced in absentia to burn at the stake should he ever return. Both bitterness and longing would mark the remainder of his life, in which he managed to produce a work of world-altering genius.

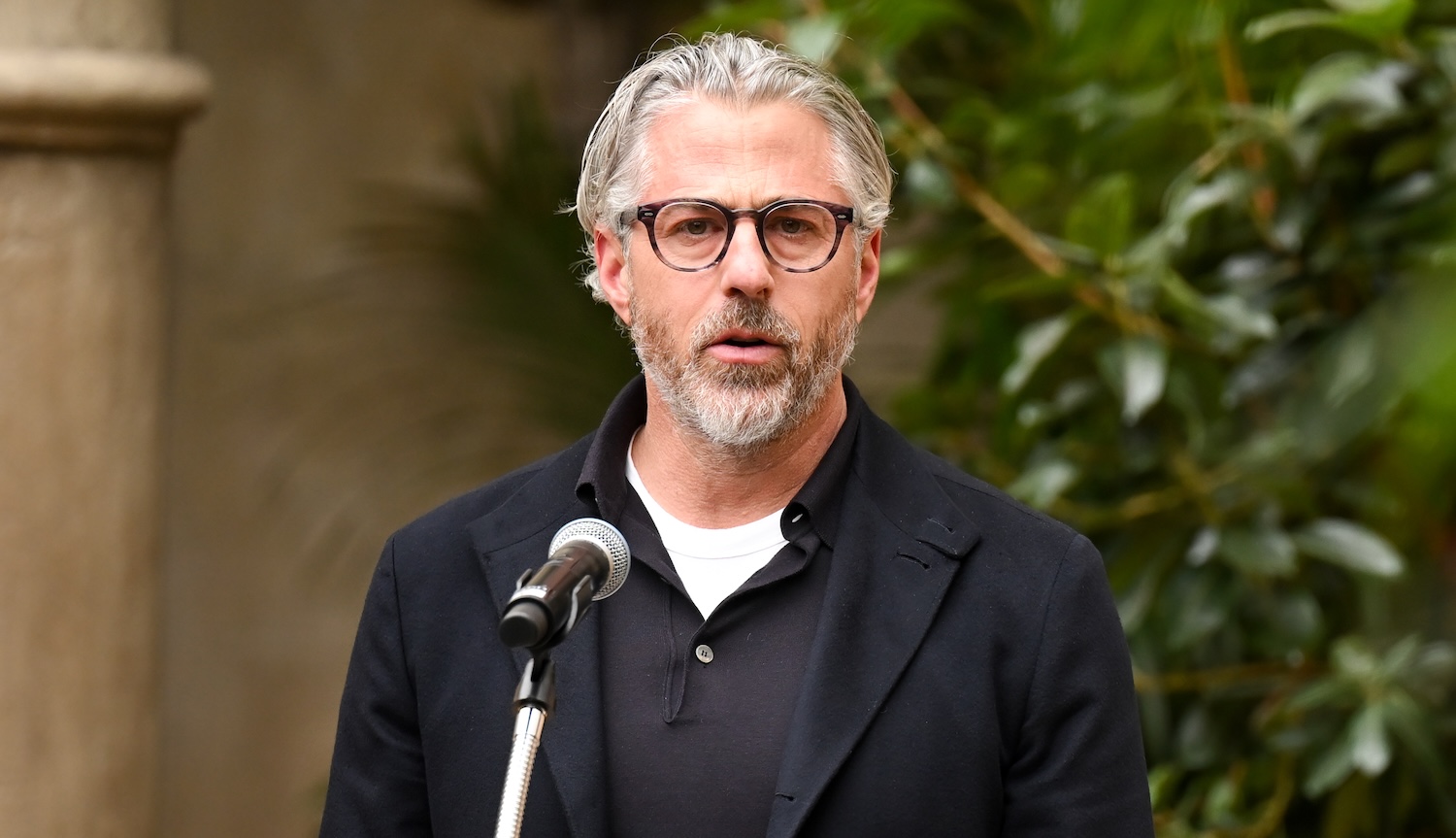

The journalist Olivia Nuzzi, hiding out for a year in California after revelations that she was sexting former presidential nominee and current U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr., wrote a memoir on her phone. The sexting, of course, was a grave breach of ethics, given she had recently profiled the then-candidate for New York magazine, where she had held the position of Washington correspondent since 2017. While there, she had made a name for herself as someone who covered the ascendant Trump movement with a certain amount of style. That she was (for D.C. media) quite young and (especially for D.C. media) quite beautiful added to the allure. The resulting tabloid firestorm and loss of her job is what drove her to the West Coast, where she worked on the book.

But Olivia Nuzzi wants you to know that she was reading Dante. If the title of her book, American Canto, was too subtle a clue, she writes that she has spent a great deal of time “analyzing different translations of The Divine Comedy,” going so far as to hire an Italian tutor so that she could better “understand the source material.” She left a copy on her dining table, alongside a Bible, that made its way into an embarrassingly gauzy New York Times profile in advance of her book’s publication.

The Divine Comedy is, among other things, an attempt to settle personal scores and prove that its author deserved to be welcomed back into Florentine society as a great artist. It describes the pilgrimage of our poet protagonist, Dante, through Hell, Purgatory, and finally Heaven, where he reports on all possible manner of sin and its consequences, wrestles with the legacy of ancient philosophy and the demands of Christian piety, dabbles in numerology and cosmology, sees angels and monsters, and generally expands the bounds of human imagination while remaining ever rooted in a vibrant and humane realism. He eschewed Latin and opted for the Tuscan dialect which he thought anyone, even women, could read. The poem’s distinctive three-line scheme would go on to confound translators hoping to render it into comparatively “rhyme-poor” English. I’d be curious to know how far Nuzzi got with her own efforts.

Along most of his journey, Dante is led by Virgil, the Roman poet he most admires and wishes to emulate. Nuzzi, as others have pointed out, seems to have a similar relationship to the late Joan Didion, imitating “not only Didion’s themes and interests but her specific writerly tics and constructions down to the sentence level.” Nuzzi, too, wants to describe a certain type of Hell and what she saw there—that of Donald Trump and the world he made—though in the sort of language that strains under the weight of pretension:

I mean to tell you of the canyon where voices carried. The place where monsters spoke to me. Where I listened. Where I found that, as fortune or curse would have it, I knew the language of monsters. Where, with news on my tongue and tears in my eyes—the role of town crier, I interpret literally—I ran back over the hill to translate for those who could not stomach the thought of standing face-to-face with monsters but who required knowledge of monsters as the monsters accrued ever more power, as they revealed or converted ever more monsters among men.

I mean to tell you that, as it relates to monsters, little can be assured beyond their ceaseless want. That you feed the monster, and the monster wants only more. That here you have surrendered to the endless transaction, and through the terms on which you meet the monster you are transformed monstrous, too, for the day that the monster is done wanting is the day that the sun does not rise; want makes the monster as sun makes the day.

Writer and Renaissance scholar Colin Burrow described the Commedia as “epic rewritten in the key of autobiography.” American Canto is a failed attempt to write an autobiography in the key of an epic. And because Nuzzi is an enormously self-regarding millennial and not a poet on a linear pilgrimage, this takes the form of a memoir in fragments. The protagonist of Lauren Oyler’s novel Fake Accounts says, of fragmentary writing: “What’s amazing about this structure is that you can just dump any material you have in here and leave it up to the reader to connect it to the rest of the work.” Nuzzi certainly avails herself of this.

Chapterless and digressive, Nuzzi goes from describing a Trump rally to reflecting on manta rays and how “the Olmecs used the sap of Mesoamerican gum trees to form rubber around 1600 BC,” which has led to the plague of microplastics, then on to discussing Jan. 6 with the president while in New Jersey. She speaks of Britney Spears and God with equal reverence. She litters the book with epigraphs from Nietzsche and Jordan Peterson. She invokes American myths—at one point describing a paparazzi photograph of herself as looking “as if someone had drained my body of blood like the Black Dahlia and strung up the shell of me at the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade”—alongside classical ones. RFK Jr. sees himself as Ulysses, and she comes to share that vision of the man who “heard his own name in the call of sirens, and recognized his fatal curiosity and longing.” Of course, this curiosity is not fatal to Ulysses himself. In Dante, the Homeric hero is consigned to eternal damnation because he used his power over others to lead men to their deaths. If Nuzzi made this connection, or wants the reader to, she does not mention it.

Like Dante’s, Nuzzi's Hell is peopled with other writers, politicians, and men of power and influence, with the greatest punishment saved for those who betray. Satan, ice-bound in the lowest rung of hell where no light or love can ever reach, has three mouths, which gnaw at Cassius, Brutus, and Judas Iscariot. At least Dante names names, whereas Nuzzi instead prefers referring to such characters as the Politician (RFK Jr.), the South African Tech Billionaire (OK, sure), the Performer (less clear), and the “failed candidate” (here, I am lost). This mostly serves to confuse, although in one particular instance—that of the “movie star” who approached her at a party alongside Maureen Dowd and said, “Olivia, the secret to life is to be rapeable…You are rapeable”—I was genuinely quite annoyed by her coyness. Maureen Dowd, please spill.

Nuzzi's former fiancé Ryan Lizza, styled as “the man I did not marry,” is a menacing presence throughout, though he likely deserves far worse. I don’t know if he hacked Nuzzi’s phone and leaked information about her affair, as she alleges in the book, but he is certainly guilty of taking full advantage of the current situation. Just before the publication of American Canto, Lizza—who, it should be noted, was fired from The New Yorker after allegations of sexual misconduct—released the first in a seemingly endless series of accusations against Nuzzi on his Substack. He is still churning them out, ending each with the breathless tone of a serialized Victorian sensation novel. Lizza may be the second-most notable worm in this whole saga, but he’s a worm nonetheless.

Whether justified or not, American Canto is tinged with paranoia. Nuzzi spends much of the book harried by fire. California burns: “Below us, fire, above us, fire. That we came from fire and return to fire, that we move forward only because we have learned to tame some fires, that here at least untamed fire is the greatest present threat to life.” Elsewhere: “We get caught up in beginnings and ends, but far afield in the belly of the horseshoe theory, the poppy burns and the lupin flames and life and death braid together in the blaze.” She recalls the day a man self-immolated outside the Manhattan criminal court where Trump was on trial, and how “the rest of the day, the rest of the court proceedings, and then on the drive uptown and then on television, I tasted him.” How he was “in my mouth as I spoke about the trial, that my words were formed by pieces of his body, that I spoke him out loud.” To her credit, this does sound like an appropriate form of eternal punishment for most television pundits in the Trump era.

Nuzzi describes RFK Jr.’s voice, “the subject of so much derision,” as “a fire crackling, a sound that made me warm.” And here we reach the central failure of American Canto: For all its use of fire, for all its varied conflagrations, the reader never gets a hint at why she burned for this man. She remains remarkably, maddeningly prim about the desire that occasioned her downfall. Of his erotic poetry (“I am a river. You are my canyon. I mean to flow through you. I mean to subdue and tame you. My Love”), she only says it is “beautifully depraved.” To be clear, I don’t disagree! I have both sent and received far more embarrassing things, and hope to again. But I do want to know why she yearned to be so full of his river. I want to know what, besides the prospect of becoming a Kennedy, drove her into his often shirtless arms.

After all, it is eminently possible to write a great book about being driven sexually insane by a man who sucks. Nordic women do it particularly well. The protagonist of If Only, Vigdis Hjorth’s autofictional account of a cataclysmic affair with a bald, whiny, often soggy Brecht scholar, manages to describe how the thrill and the shame of it can overturn a life. She does this with both ruthlessness and compassion. Desire that leads one to the brink of madness is one of the more interesting things that can happen to a person, but Nuzzi hardly seems interested in how it happened at all. Rather, she casts herself as oddly passive, saying that “the hand of God reached down to swat me off the path I was on. God struck a match. God struck me again.”

Despite Nuzzi’s initial promise to tell about “how it happened between me and the Politician” and “how it happened between the country and the president,” because she “cannot talk about one without the other,” she breaks that vow twice over. Of the country, she offers little more than reheated versions of what we already know. A decade ago, reporting back from the infernal regions of Trump’s America may have been a worthwhile undertaking. At this point, the demons have long been loosed upon the earth, and they are happy to speak for themselves. They do it on podcasts, Twitter, more podcasts, and television. I do not need someone who will run “back over the hill to translate for those who could not stomach the thought of standing face-to-face with monsters.” My stomach is sturdy enough. Nor do I need the bigotries, depravities, and meanness of these people laundered in hilariously grandiose language—we have The Free Press for that.

The one thing Nuzzi could offer to a reader is the one thing she refuses to provide. In aiming to elevate, in setting her sights on Gemini moons and drones that fly through the air, she fails to understand that this kind of story could only be credibly told by lowering herself. It’s a squalid business, and probably wouldn’t have redeemed her in the eyes of many, but it might have offered something approaching the truth.

Among Dante’s great inventions was constructing a vision of Hell where the punishment borne by sinners reflected something of their sin. Fortune-tellers have their heads twisted around, so they can only see what’s behind them. Adulterers are locked in an embrace and battered about by ceaseless wind. It’s fitting, I suppose, that for attempting to be a poet, Nuzzi is instead consigned to a lifetime of having her name on this book.