I was a man with a simple goal: to sell a grid of nine original MS Paint drawings of Jason Whitlock in various Halloween costumes on the NFT marketplace, rake in a glorious haul of cryptocurrency, and become a trillionaire. Sure, there were some obstacles. I did not know how to make a grid of nine different drawings. I did not know what the words "non-fungible token" meant when combined in that order. I did not know how artwork becomes a "non-fungible token." I did not know where people go to buy or sell "non-fungible tokens." I did not understand cryptocurrency. I did not know where people go to exchange real money for cryptocurrency. I did not know how to take even the very first baby steps in any direction in this imaginary new sector of the global economy. But a man will do desperate things to become a trillionaire. Besides, I had already done the hardest part. I had drawn Jason Whitlock in nine different festive Halloween getups, for a night of Defector trivia back in October 2020. The rest is just business, and if there's one thing I understand even better than doing high-brow artwork, it is how to do big business.

Unfortunately, between the time that I started that paragraph and the typing of the word "business," the market for non-fungible tokens crashed, and my window for becoming rich enough to buy Defector out of this silly worker-owned model and turn it at last into a full-time Wizards fan blog slammed shut forever. Things are now headed in all kinds of insane directions. A digital artist named Michael Winkelmann, known as Beeple, sold an ugly digital drawing in an NFT auction for a staggering $69 million of cryptocurrency on the Ethereum blockchain, then turned around and cashed out his cryptocurrency haul for cold hard cash and called the entire thing a bubble. That harsh appraisal has not stopped Tom Brady, Vernon Davis, and the dreaded Manning brothers from launching their own NFT enterprises. Meanwhile NBA Top Shot, which saw roughly one jillion dollars change hands in the sale of images of things that happened in NBA basketball games, appears to have been caught by reliable old reality.

@topshotanalytix @economist @girldadNFT for everyone wishing they got into TopShot in Jan instead of Feb. Well ... welcome to January. pic.twitter.com/IY1TslV8I0

— ☄️☄️☄️☄️ (@jfresshhh_) April 3, 2021

Blockchain things are still happening, of course, and will continue to happen for quite some time. The bloated, terminal, outgassing monstrosity that is American late-stage capitalism has never been more desperate for some insane new unregulated frontier for separating fools from their money, and this is that. The project is breathtakingly, howlingly made-up. Digital images are infinitely abundant and infinitely replicable: What NFTs do is artificially inject the merest notion of scarcity, by pretending that chiseling a record of ownership onto a digital ledger grants real monetary value to a particular iteration of an infinitely abundant, infinitely replicable thing. There may be four million versions of the Crying Jordan meme floating around the internet, and that number may grow exponentially by the year, but if a 256-character code can certify that you paid for "ownership" of the very first of them, clearly that is something that you should pay for with your entire life savings, even though ownership, in this case, grants you no legal rights whatsoever.

The real winners in all this are miners of the various cryptocurrencies designated for NFT transactions. For example, on OpenSea, a marketplace for buying and selling digital artwork as NFTs, the very first thing you must do in order to participate on either end, as a buyer or as a seller, is create a cryptocurrency wallet and load it up with some ETH, which is the cryptocurrency used for transactions on the Ethereum blockchain, where NFT ownership data is stored. Ostensibly this is so that you will have the funds on hand to pay what is called a "gas fee" associated with blockchain transactions. This is a pretty literal term: the Ethereum blockchain, like all robust blockchains, requires insane, ungodly amounts of computing energy to continue functioning, and every time new transactions are added to the blockchain, its energy needs increase. You can start to see a problem on the horizon, as the energy demands of maintaining various blockchains into the future skyrocket beyond all comprehension. The real losers in all this are anyone who plans on living on the planet Earth 20 years from now, baking in the dust as the 19 people who control all human wealth ride a spaceship to their tricked-out orgy pad on Mars.

It's all extremely crazy-making, especially for the sort of person who walks into a museum, sees original artwork all over the walls, and both feels and wants to feel that art has intrinsic value and important cultural value. There's something incredibly profane about art—even crappy, throwaway digital art, even memes—being turned into a financial instrument, and especially when that's in service of a technology that is actively, defiantly attacking our actual home planet. This, to me, is probably why so much of the shit being sold as NFTs is, in fact, shit: algorithmically generated illustrations of ugly cats, and flamboyantly ham-handed, Resistance-brained political cartoons, and cell-phone videos of people ripping farts. I have to believe any artist with more brains and heart than, like, Ben Garrison would flatly reject the post-human, anti-life characteristics of NFT business. I fucking hope so.

At any rate, it's more than I can take in or gather up without reeking ooze pouring out of my ears. Thankfully, there are good and smart and conscientious people who spend their professional lives keeping both eyes trained on this mess. For help making sense of it all I tracked down one of them. Dr. Rachel O’Dwyer, a lecturer on digital culture at the School of Visual Culture at Ireland’s National College of Art and Design, has deeply researched and thought long and hard about cryptocurrency and the many different ways of conceptualizing the intrinsic or cultural or financial value of art. She has been studying cryptocurrency and blockchain technology longer than I have known of the existence of those words, and wrote a fascinating and somewhat troubling essay for Circa, titled "A Celestial Cyberdimension: Art Tokens and the Artwork as Derivative," all about art as a financial instrument and in particular as blockchain fodder in our strange new world. Dr. O’Dwyer spoke with Defector from Dublin last Thursday morning. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

So, first things first, how did you get into blockchain and cryptocurrency stuff?

Well, so, I'm really bad with money, generally. My husband and I are actually trying to apply for a mortgage at the moment, and I just have so much anxiety about how bad I am at money. But I'm really interested in money, I guess, and in places where money, art, and technology intersect. Towards the end of my PhD I was scouting around for jobs, and this position came up for a researcher in money and new media, in the Institute of Network Cultures in Amsterdam, and something really clicked for me. I’d been working on the social and political implications of mobile technologies up until then, and then I really realized, I guess, that money is a technology and money is media. But it's this technology that's kind of hidden in plain sight that we don't really pay a lot of attention to. And so I realized that by looking at money I could ask all kinds of questions about how value is produced and how we imagine the future, through money and through media. In the end I didn't actually go for the job, it just ended up being a way for me to sort of think about research I could do in Dublin. That's how I got into money.

By 2013, when I started looking at blockchains and cryptocurrency, I’d kind of missed the very first blush of Bitcoin enthusiasm. I was studying money and media, and then I was part of a group called the P2P Foundation, which is not really an academic group so much, even though researchers are involved—it's sort of like an open source community where people are working on things like open source software, open source hardware, community wireless networks, that sort of thing. And there was, I guess, some interest in Bitcoin and blockchain as technologies that could imagine fairer forms of money, but also maybe could be used for, you know, different kinds of governance. I guess both of those two things kicked off for me in 2014. So it was after Bitcoin, but it was right before Ethereum. I was researching Ethereum before they released their first ICO, their initial coin offering, when they were just having virtual meetups.

I want to ask you, like, what THE FUCK is a non-fungible token, but I get the sense that first we will have to talk about blockchains and cryptocurrency, which I also do not understand.

Yeah, I think it’s useful for me even to just go back over it in my head. So, I really do think of blockchains in a very basic way. A while ago I did go into quite a lot of detail on like the history of blockchains and where those ideas came from, and digging down into the history of cryptographic proof, but generally, if I'm trying to explain what a blockchain is, I would just say it's like a decentralized ledger. Most ledgers are centralized, meaning that one trusted party gets to control the information recorded on the ledger. So, for example, if you're in class, and your teacher takes attendance at the start of class, that's a centralized ledger. The teacher marks you present or absent and if you disagree, if you say, “Hey, actually I was there on Tuesday,” there's not much you can do to contest the information in his or her ledger. A decentralized version of that roll-call would have every student in the class take attendance each day, and do so in permanent marker so that the results can’t be changed or falsified. And then we compare them all at the end to make sure the information is accurate. So no person in that class, no one individual would have control.

Another centralized ledger is controlled by your bank. Your bank keeps track of what money is in each account and your credit and debit accounts accordingly. The blockchain decentralizes that process: Instead of one person or one trusted third-party or intermediary being in charge of the records, everyone produces the records at the same time in a way that makes it impossible—or nearly impossible, anyway—to falsify the record.

Blockchain is a ledger or database, hence why it is sometimes called “distributed ledger technology.” The way the blockchain works to stop someone from falsifying is via a cryptographic mechanism called a “proof-of-work.” Each time a new record is added to the blockchain, a miner performs this computationally expensive calculation, this sum, basically, that takes time and energy. We've heard a lot about that, of course, how much energy these take to complete. So to falsify an entry on the blockchain, you would have to go and redo all of that work, all of those sums, all of that math, back to the beginning of the blockchain. It's far too complicated and would take too much time.

It's interesting, this technology has origins in proposals for managing spam. The idea was basically this: In order to stop somebody spamming people with emails, you'd add an arbitrary little bit of work to sending an email, like having someone do a calculation, like what's 10 by 32. That's of course really trivial if I'm just sending an email to you, but it's prohibitive if you're blasting out thousands of emails. The Bitcoin blockchain uses that Hashcash proof-of-work model, basically, to prevent double-spending or fraud, to prevent people from sending a digital token and spending it at the same time. I guess that's a problem with digital objects, or tokens, is how do you know if I give you five euros or five dollars, that the token really has passed from me to you? What Bitcoin I suppose is solving is, it's sort of producing for the first time this digital scarcity where you have a record of this digital thing that makes it unique and scarce, and a reliable record of it being passed from me to you.

I’ve heard people describe the decentralization essential to blockchain technology as a sort of democratization, this lofty idea that it disrupts a corrupt banking system or even corrupted marketplaces and replaces them with, I dunno, a non-hierarchical network of all-devouring server farms? But is the thing that’s being democratized here essentially just, like, authentication? Is the utility of this technology that it authenticates transactions?

That's a good question. Because I think in a lot of cases there are these, like, proposed applications for the blockchain where actually, when you look at it, like, did you really need a blockchain for that? And often the answer is no, you did not. We are seeing blockchains being made useful in supply chain management, to prove the provenance of goods, like, say, military equipment. It can show, where was that produced, has it been tampered with at any point in the supply chain? Or, for another example, where did your fish come from, and was it ethically sourced? But in a lot of cases blockchain seems to just be lip service for digitalization of applications that have really long paper trails.

In the case of money, after the financial crash there was a sort of widespread loss of faith in the banks and the banking industry. So people found blockchain exciting in that sense, because it sort of allowed you to create a record that couldn't be controlled or falsified by any one central intermediary. And that's sort of what was attractive around it. With Bitcoin, that record was basically just about who had any token at any particular time. But as blockchains have become more sophisticated, the information now has kind of moved from who owns the coin toward the encoding of other information, like the ownership and provenance of real assets, like land, precious metals, and physical and digital works of art, or things like digital goods, like music or images.

And also, I suppose, it’s moved from just kind of storing information about who has a coin, or who sent a coin to somebody else, toward being able to store that information about the ownership of lots of different kinds of things. Not just coins, but also what are called “smart contracts,” contracts that execute on the blockchain that do slightly more sophisticated things than just transferring ownership of something. They maybe allow for multiple people to be paid, for example, or allow for different kinds of rental relationships around goods. So as it’s scaled up, those kinds of contracts, and the kinds of goods that can be associated with them, have become maybe more sophisticated.

Which brings us, at last, to the dreaded non-fungible token. I think I know what the word “token” means in normal language, but what does it mean in the context of blockchains?

That's such an interesting question, I think. I'm thinking of an example, like take my student union, which didn't have a license to sell beer when I was in college. So you gave somebody at a desk five euro and they gave you a token for a beer. Tokens in that way are kind of money-like things, they kind of function like money, but in the blockchain they're not often linked to a particular utility or service. So they kind of are like money and aren't like money.

That's what I find really fascinating about digital money, with so many different platforms creating these kinds of money-like things. So you have mobile network operators in the global marketplace who are issuing currencies that are backed by phone credit, or airtime. You've got performers on streaming websites being paid in these kinds of specific sub-tokens that are specific to those platforms. To think about these tokens, they're kind of what economic anthropologists would call “scrip,” which are these informal currencies that act as substitutes for legal tender. Think of cigarettes in a prison, for example. It seems like they’re sort of a way for these platforms or these companies who aren't actually financially regulated or maybe don't have a financial license to basically issue their own money, by issuing something that is like money but isn't. I think what a token is is really interesting, but is also surprisingly hard to pin down as well.

My wife tried to break it down for me by referencing the little fake coins the machine spits out at like a video arcade, but in the case of arcade tokens those can only be used to purchase time on one of the games or maybe some crappy toy at the little prize counter. It’s funny to think of taking my sad little pile of arcade tokens and stashing them away for a time when they are worth more than they are today.

It really is an interesting question, though. I did some work over in Irvine a couple of years ago, around the time that there was loads of speculation around ICOs, these initial coin offerings where companies were issuing cryptographic tokens and people could buy them. With those tokens there was supposed to be a utility. As with your wife's example, they were a thing that you buy that gives you access to something. So mine was access to beer, your wife's was access to video games, or maybe you buy tokens for laundry, like to use a dryer or a washing machine. The token allows you to use this service. But the thing that regulators were getting anxious about was that a lot of the tokens actually didn't represent utility, their value was entirely speculative. They represented some kind of security, or assets associated with the company.

The other really interesting thing about this is the non-fungible nature. But I think to really understand what NFTs are, it is good to kind of distinguish between tokens that can be exchanged for lots of different things and a non-fungible token, like a digital work of art. It’s worth digging into what the word “fungible” means. Economists speak about money as being fungible, that any five-dollar bill is supposed to be as good as any other. But it’s kind of a funny one, isn’t it? It’s true in principle, but it’s not always true in practice. Like, do you have any money or coins that you feel sentimental about?

[affronted] Certainly not.

[wise and patient] Really?

[owned] Hmm. Well, actually my wife and I do have two two-dollar bills in a keepsake box that were given to us by her stepfather. So I guess I do!

Yeah, like, I have a 20-euro note that I was given, like, someone sent me in the post, just as an engagement gift. And I wouldn't spend it. Occasionally, if I order takeaway and have no cash and I forgot to pay in advance, it kind of flashes through my head—oh, it’s there—but I just can’t do it.

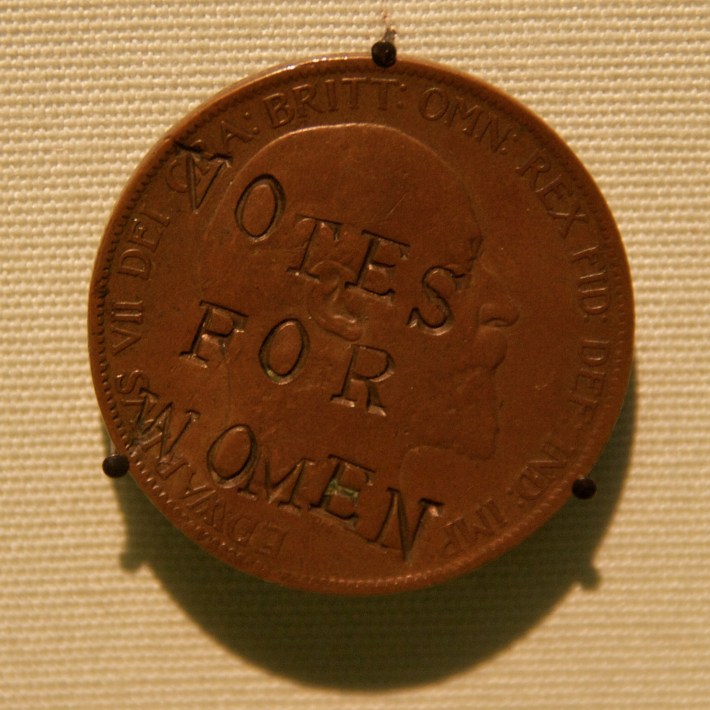

And, like, people collect centennial coins, and people will mark coins. In the UK, during suffrage, the suffragettes marked up coins with demands for votes for women, they etched into the physical coin, “VOTES FOR WOMEN” across the face of the monarch, and then spent the coin back into circulation, like some kind of proto social media. So those coins were marked in a particular way to make them kind of non-fungible. And I'm sure they're worth way more than other British coins.

A non-fungible token is a token, only it’s special the way a collector's coin or a baseball card is special. I guess the difficult thing is it doesn't usually give you any rights to anything. All you own, in a lot of cases, is the contract itself. There’s nothing genuinely tangible associated with that, nothing you can hold in your hand. What you're getting is a unique proof-of-ownership over a thing that, in a lot of cases, isn't really a thing. With a lot of the NFTs now, you get a certificate that points to a URL, but that image can disappear. It’s just a little bit of code that references a piece of media located somewhere else on the internet.

But in the case of the $140,000 Cryptokitty, which is just a stupid little algorithmically generated illustration of a cat in an endless set of nearly-identical algorithmically generated cats, no one can possibly make the case that the superficially unique characteristics of this or that cat illustration make it more valuable than any other, to say nothing of exponentially more valuable. Right? It makes me feel very insane to know that someone spent $140,000 on a digital illustration of a cat spat out by a template operated by a script.

Celestial Cyber Dimension is on display at @ChristiesInc fur the @CodexProtocol #EtherealNY charity art sale. The live auction starts tomorrow. https://t.co/jkhtKtjsb2 pic.twitter.com/GPX3lAuKEO

— CryptoKitties (@CryptoKitties) May 12, 2018

I thought that one was really interesting, because, like, what do you get when you do that? When I wrote the article for Circa, I was speaking to people who were involved in that particular auction, and one of the things that they said was that often when buying art—you think about why people buy art—it's not always because they love the art. Frequently, more and more, people buy art as a financial asset. So they buy with their ears rather than their eyes. You're buying because you think this thing is going to increase in value.

I remember reading a book about the history of art markets, I think it's by Noah Horowitz. And he said people buy art because it's a way of signaling. It says something about you if you buy expensive works of art, you're not just investing in the artwork, you’re also kind of investing in your own reputation or your social capital. With something like the Cryptokitty, I think you have this new kind of crypto-wealthy community, people have loads of crypto-wealth, so buying something like a Cryptokitty can earn you a kind of bragging right. In a way you're buying into your own reputation, you're buying the right to brag that you own this thing. And then of course people buy them to invest in speculation, as well.

But their value is locked to the blockchain in a way that makes my brain hurt! Like, if I screenshot all the Cryptokitties in existence and printed and laminated them and set up a store somewhere, they would be worth next to nothing, because they are ugly and stupid and there would be no value for the purchaser beyond the right to throw them in the trash. What makes them valuable to the people for whom they have value is that they are being spit out by a computer somewhere and there is a blockchain that authenticates the uniqueness of each new one. But that is accomplished by a 256-character code! The only reason to even illustrate the Cryptokitties at all is as a kind of visual shorthand for each one’s uniqueness. You are purchasing an encounter with uniqueness and a certificate that your encounter was authentic. There are no merits!

Well, my feeling is, I find it really interesting because I was thinking about it in relation to shifts around art and art markets more generally. But it seems like, more and more, you're seeing a shift from art as sort of a commodity, or art as a craft item, toward art as a derivative, which is a kind of financial instrument, and where what's most significant, actually, is the information or the hype that circulates around it. To me art on the blockchain is a really good example of this. Maybe since the financial crash, we’ve seen the rise of art as an asset class, and the rise of funds that specifically buy art, to hedge against volatility in other markets, and of people using art as security on loans, and generally investing in the idea that ownership of art might make you money in various different ways in the future.

This idea of the derivative is, you know, you've got stocks and bonds, and stocks represent assets and commodities in a market, and bonds represent a claim to a debt obligation. Derivatives are these weird financial instruments, they function sort of like betting on the performance of stocks or bonds.

If this is art moving into the derivative class, is the thing that NFTs reference the performance of cryptocurrency itself? Or like the cryptocurrency undergirding the particular market? Is a given NFT a bet on the performance of the blockchain?

Oh, what is the bet on? Yeah, that’s interesting, because I think a lot of the examples we’re seeing, like with the Beeple auction recently, it's a kind of a pump-and-dump thing where you're inflating the value of the currency through hype. So I think you're probably right, the thing that's being inflated is actually the underlying value of the cryptocurrency or the token.

But also, you know, there's a sense that increasingly the work of art itself doesn't matter. It actually doesn't really matter. All that matters is the certificate of ownership and the hype or the information around the sale. Like you said, you could print off all of those Cryptokitties and sell copies of them! Having something on a blockchain. It's not like a form of digital rights management, it doesn't stop other people from copying the image or circulating it on the internet, all it does really say is that you own this particular limited edition or iteration of it. And all that you really get, you don't get rights to the images, as you said, you don't get a physical thing, in a lot of cases you just get the certificate of ownership.

So if what matters is that the thing is unique and that your ownership of it is authenticated, but you never take possession of the thing and have no enforceable rights to it, aren’t all the things therefore identically valuable? Every unique thing is equally unique, and every authenticated purchase is equally authentic. As a buyer, if you bring any aesthetic preferences into the marketplace, aren’t you automatically a sucker? Like, if you pay more for uniqueness and authentication than someone else, because you want your stamp of uniqueness and authenticity to be blue instead of red, aren’t you a fucking rube? Just screenshot the blue stamp!

It's an interesting question! It comes back to that question of like, why? What are the various different motivations and reasons that people buy art, and quite a lot of the time, they're not all that aesthetic.

For example, just to kind of familiarize myself with how it was working now, in 2021—because a lot of the research I did was in 2018 and 2019—a guy I used to work with, Bill Maurer, who's kind of like a money expert, somebody had created an ASCII—you know those old hackery kind of images? They’d made an ASCII portrait of him that weirdly was encoded in the blockchain itself. A lot of the works we're speaking about, they're not located on the blockchain. Generally just ownership information is on the blockchain, but there's a couple of exceptions. There's a sort of crypto-graffiti, where people will actually encode these very small images into a blockchain. There's a website called something like Cryptograffiti, I'll send you a link. I think you can store up to something like three megabytes in a hash on the blockchain, so you can't really store a big digital file, or anything like that. Most of the time what it stores is the ownership details and a link pointing to like a digital artwork or a physical good. It's something like the fingerprint of that good, like, say, diamonds or something. But occasionally people store actual images on the blockchain, if they're very, very small.

Anyway, this portrait of Bill, somebody made an NFT of it recently, and he emails his friends to say “Buy me, I’m on Mintable!” So I went on Mintable and I got in the auction. But then when I won it, actually, the gas fees were astronomical! So I won the auction for the image and the image is like $1.20, but then when I went to pay, the gas fees for Ethereum were like 60-something. And that was just way too much for me for like an image associated with Bill Maurer. So I just left it.

But I think it’s really interesting because I did want to buy it, to show off a little bit!

I read about that rose NFT in your essay, is that one of the crypto-graffiti deals? I had a hard time wrapping my head around that whole thing.

No, no, Kevin Abosch’s “Forever Rose” is an interesting one, but it’s not an example of this. I find that really interesting. A lot of the works we’re talking about, we’re like, “This is a digital work,” and we're pointing to this thing. And so maybe you have an artist who makes a digital work and their gallery will produce some limited editions with high resolution and then you can buy an NFT that represents ownership of that limited edition. Kevin Abosch’s pieces are kind of blockchain-native, I guess, in that there's actually no physical version of it, and there's no digital version of it. The artwork actually is the smart contract. And so he made this piece, the “Forever Rose,” that didn't exist in any physical or digital sense. It was just the token. So that was kind of interesting.

Wait. But when I read your essay there was a picture of a rose. Was that not a digital representation of the work? My brain is absolutely swimming right now.

I guess it's funny, isn't it? In that case, he did actually have a picture of a rose, which was kind of like for publicity purposes.

But that image of a rose, which exists to represent the “Forever Rose,” is not the “Forever Rose.”

Yeah! It’s a bit weird, because I had to email him and his gallery to get permission to use that image, I remember, but actually the “Forever Rose,” the art piece, wasn't actually associated with that image, or any image at all. It was a bit like the centenary coin, it just consisted of the token from the smart contract. So the art piece was the contract.

[quite literally sweating from confusion] OK?

There’s this really early work that I really want to write about, because it reminds me of, it's kind of like an NFT in reverse. A lot of the works we're looking at here, the ownership becomes the entire work. That's the whole point of it. But I remember coming across this piece by Yves Klein, who was a French performance artist from the 1960s. It was called something like “Transfer of a ‘Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility.’”

The piece was, he sold imaginary zones near the Seine in Paris. They weren’t real zones and they didn’t exist except in his head, but you could buy one. To buy it you gave him gold, and he gave you a little certificate. But then, to complete the performance—and, thus, the artwork, and of course the sale of the artwork—you would burn the certificate and Klein would throw half the gold into the river. I find it really interesting. It's kind of the opposite of the NFT, I guess, in that he says in order to actually possess this, you can't possess it, it has to be destroyed. Maybe the reason I’ve been interested in this is that there's a lot of work that tries to deal with some of these ideas around, you know, discomfort between art and the market, and art and money, and art as currency.

That's cool, to me, a piece or performance that completes its commentary by … ceasing to exist? Or is presented or transacted in a way that subverts the perfectly sensible expectation that it … exist in the observable world?

I think it's such an interesting thing! I think it was like the 1960s and 1970s when you had a shift toward conceptual art. There was a famous book published at that time by a critic named Lucy Lippard, called The Dematerialization of the Art Object. It presents this idea that art would no longer have a physical form or be a physical thing, but would just become a concept, like conceptual art. And they saw this as being a way as well of defining the relationship between art and the market, because you know, if there wasn't a thing or a commodity, the market should fall. But what we've seen is that actually this de-commodification of art doesn't actually really perturb or disturb the market the way you would expect it to. Conceptual art functions in a way like limited editions, you know, like the “constructed situations” of Tino Sehgal. There's a story where somebody tried to sell a Tino Sehgal on a secondary black market!

What would that even mean!

Yeah, I know! So, you know, there's always these sorts of ways of making something that can be sold. I think a lot of work sort of grapples—there's this kind of reflectivity thing where the work is sort of reflecting on its own position within the market or trying to deny its own position. Banksy’s work I think is a really good example of that. You know, that famous Girl with Balloon piece where once it was sold at auction it shredded itself. And people were saying at the time, “This is so amazing, he's done this really provocative ‘fuck you’ to the art market.” And I just remember thinking at the time, like, no way! The funny thing about art is it's supposed to be this exceptional economy, a bit like things like blood donation or surrogacy, it's one of these things that we feel a little bit uncomfortable with being in a market, we sort of feel like culture should be free.

And so to be successful, actually to be financially successful often I think artists have to sort of deny their own position within the market. So the Banksy, it's kind of a double bluff, in a weird way: In order to be seen as making, you know, legitimate art, he has to somehow also be seen to be denying that market, but not really.

Right, like if an artwork lands too comfortably in the market, or if an artist is too brazenly commercially oriented, then not only is it a kind of sell-out project, but also it loses credibility as art, which is supposed to exist for its own pure purposes.

Yes. Although I suppose you do wonder, I’ve been thinking about it—yes, I think a lot of the time that is what’s happening, you seem to deny the market in order to remain credible—and occasionally you have artists who sort of parody the financial system in their work, like Damien Hirst, or even Andy Warhol. But even then, I suppose there's a sense that by doing that, it's almost like a pastiche or a parody of this thing, you know, that you're poking fun at it in some way, by participation or by over-investing in it. But not really, because, you know, Damien Hirst’s work is in fact very, very valuable.

On the subject of where art sits in the marketplace, can you please explain the whole free ports thing? Learning about this was one of those moments where I wanted to walk into the woods forever.

Oh yeah! Free ports, historically, are these extralegal spaces where goods enter a country before going out again. Normally there were ports in countries where things like tea or grain would come in, but there were expectations that they would go out again, very quickly, they're just there for a very short time. So the free trade zone is a space where you didn't pay duty on this good coming into the country, because there's an expectation that it'll leave again, pretty quickly.

What's happened, though, is that there are these spaces now that exploit that extralegal, offshore aspect of the free port. I visited a free port in Geneva, for example, it’s a couple of square miles, on the outskirts of Geneva, in Switzerland, which in general is associated with offshore financial practices. This free port is a space where people who own goods that are stored there don't have to pay duty to bring that good into Switzerland. If you buy a really expensive work of art at auction, and you ship it to your home country, you're going to pay a lot of taxes. So by shipping to a free port, you don't have to pay tax associated with the work to move it from one place to the other. The idea was that things were only supposed to be stored there temporarily, but people exploit that loophole to store high-net-worth assets, like cars, and art, and fine wine, and gold bullion as well. And they get stored there indefinitely.

There's some really depressing statistics about how much art is stored in some of these free ports. The Geneva free port, I think, is supposed to have more contemporary art than MoMA. Millions and millions of dollars worth of art. It's kind of interesting, because there's all of these different new kinds of financial instruments around art, like art-backed securities. From what I understand, people can kind of leave the good in the free port, but like a bank, and then use it as collateral in a loan—they can use it to secure a loan—or you can wait until the moment is right, until the work is valuable enough, to resell it, and in some cases you can resell the artwork without it ever leaving the free port. The free port becomes like a bank for art.

It’s awful to think of original art sitting in a warehouse in some offshore port, changing hands for financial reasons but only in the most technical sense, accruing or losing financial value, but essentially being stripped of any actual cultural or aesthetic value whatsoever.

Exactly. But I read somewhere, recently, that because you have this financialization of artwork, where the work never gets to be seen, it's just hidden away, that maybe one positive thing about NFT's is that at least people get to see some version of that work in circulation, that your work is viewed more and exposed more. So, I don't know, maybe that's a kind of silver lining.

So, I have what is probably an insanely dumb question. In a free port type of situation, where the artwork is never seen by anyone or appreciated for its aesthetic qualities, and exists primarily as a reference point for financial transactions, is it necessary that the work actually exists? Couldn’t you just sell a blank canvas sitting in a Geneva warehouse, with, like, an agreement that at some future point Banksy or someone will draw something on it? Once the concept of “artwork” is stripped of any cultural or aesthetic value, does the token need to be an actual artwork in order to occupy the “artwork” space in the transaction?

Yeah, I mean, I think you’re completely right. Wow. Yeah, that’s a really interesting proposition, this idea—because you have these ones where obviously it is something already, but imagine, as you say, if it was not that thing yet, but at some point in the future it will be. You’re really getting at—it’s kind of mind-blowing, because it is so self-referential, at what point can you just completely gut this of any real commodity or asset and have it still maintain its value? Which I guess is what is happening with NFTs, you know? It shows that you can, actually, you can do this.

Maybe this isn't so surprising though, If we think of the difference between commodity money and fiat money. Until 1971, the dollar was backed by the value of gold, but after this point, it wasn't propped up by anything at all. Fiat money isn't backed by a commodity, so governments have more control over how much can be printed. When you think about this it's sort of mind-blowing. The money we use isn't backed by anything more than our trust in the state.

I think to a layperson even the idea of art as a financial instrument seems like a perversion, because art is supposed to have this intrinsic, human value. So art as a derivative is real dystopia shit. And when I was reading up about this stuff, it first occurred to me that NFTs ultimately are maybe just producing a digitalized version of something that is already afflicting the art world. But, weirdly, by turning art into this bizarre crypto-financial instrument, and then saying that the thing that makes any one of these weird financial instruments more valuable than another is whether you like the pretty colors, we’ve come full circle? In the most breathtakingly cynical way imaginable, we have reinserted aesthetic appreciation into the art market? I hate everything right now.

I think the term you just used is the one we were both feeling for there. What we're asking is, is there any intrinsic value to a work of art? Does anything’s value come from its intrinsic value? Like, is gold intrinsically valuable? Well, not really. Right? It doesn't have a use-value, you know? There's Veblen goods, which are valuable because they're expensive, like Birkin bags, which are valuable because they cost loads of money.

And which one of these is art? Does it have use-value? Is there something about this particular work, like the Mona Lisa, that's intrinsically valuable? Because it’s so aesthetically beautiful? Or is it valuable, like a lot of these works, because it’s valuable? I guess the questions we’re poking at, there, with the Banksy that doesn't even exist yet (which I think is probably going to be the next big thing), is, like, what is value? And what is intrinsic value? You know, what makes something economically or socially or aesthetically valuable?

You had a really good summary of Horowitz on what motivates the art buyer, and signaling playing a role in driving the purchasing of art, which made me think about how there’s kind of a whole new tech zealotry growing around cryptocurrency and the concept of tech disruption. It seems to me there are motivations that could drive a person to participate in the NFT craze that might otherwise be alien to an outsider. Like, there are some pretty prominent people whose entire identities, or at least their public personas, are wrapped up in the viability and durability of our current moment.

I think you're right. And a lot of them are tied in some way with the speculative value of, like, tech startups, or with blockchain startups. I was chatting with this guy, Finn Brunton, a couple of weeks ago, he wrote a really interesting book on the history of digital cash. I was asking him for his take on NFTs, and he said something quite interesting. I asked him why everyday people maybe are interested in NFTs, and he framed it in terms of the disenfranchisement, I guess, of the Millennial and Gen Z generations, particularly in the U.S. I can definitely relate to what he was describing, where you have this generation in debt, who maybe realistically won't ever own homes, it's not like they have loads of financial assets or wealth, where they could invest intelligently in low-risk sorts of spaces. So why not try and, you know, invest in a dream, or in a sneaker, or even, yeah, a Cryptokitty, and hope that you're going to win big? You don't have anything to lose!

That makes me wonder what would happen to the NFT market, or to various blockchain currencies, if you cleared out every speculator—people just hoping their investment will gain value—and all the people driving up prices by introducing aesthetic preferences to what are essentially 256-character authentication codes, who I am calling suckers. What would happen if the only people doing business with blockchain currencies were true believers, people who prize—or even fully grasp—the utility of blockchain technology itself?

That's kind of an interesting thought. Since Bitcoin, in particular—Bitcoin is designed to be a deflationary currency. So if I put 20 euro in my drawer, it's worth less in three years. Bitcoin, because of the way it's mined, it gets progressively harder to make Bitcoin and therefore 20 Bitcoin is worth more in five years than it’s worth now. So people are kind of incentivized in a weird way not to spend Bitcoin. What you see around all of these is that they're treated as assets. They're speculative. They're not treated as currencies. There's not that utilitarian aspect of it being something that you use to buy things, like currency, or use to fund artists, for example. That's not really happening. As you say, if you cleared out all the speculation, maybe, maybe there could be some kind of utility to these. But right now there isn't any utility. There's just speculation.

It reminds me of the death vortex of big publicly traded retailers, where once they reach a certain saturation, the only way they can continue to show increased profits is by gutting the business. Or, for that matter, the housing bubble, which fundamentally could not survive even a plateau of housing prices. But even worse! Because in the case of blockchain currency, 10 years from now the computing energy required to create more Bitcoin is going to be even more urgently environmentally catastrophic than it is today!

I think I read somewhere that it was something like 79,000 kilos or something of carbon dioxide emissions for the Beeple sale. People are experimenting with “proof of stake” (PoS), which is another way of guaranteeing transactions on a blockchain, and I guess the idea is that you're not going to fuck over something you have a stake in, and it's less computationally expensive to prove stake than to prove work. So you're not going to falsify something if you've got a stake in it. So that’s sort of another, more environmentally sustainable, way, I suppose. But yeah, right now, the emissions, the environmental impact is just insane.

Before we wrap this up, I feel that I must show you my incredible work of art.

Is this something … have you made an NFT of this?

No, well, I couldn’t even begin to figure out how to do that. But surely it is worth a million billion dollars? [shares screen]

[history’s politest chuckle]

I think it’d be interesting, you should maybe make it an NFT. I think there's different versions where you don't pay transaction fees as well. It's always really interesting to do an exercise like that, to get familiar with actually what's going on.

Yeah, I just don’t want to have to buy like $2,000 worth of Ethereum coins or whatever just to explore this craziness.

No, no. No.