It's Monday night, and I check my local TV listings to see what women's college basketball games are on. I make a note to catch all the big women's college gymnastics meets coming up on Friday. I dutifully add all the dates for my local NWSL team's games to my calendar. It seems and at some level just is incredibly normal to be watching women's sports at big stadiums and on TV, but I'm also old enough to know that all this progress is due not to moral clarity or some belated public awakening to how good women's sports can be, but to a pair of classic American forces: unintended consequences and bureaucracy.

Women's sports has always hung on by the thinnest of threads. They are not mentioned even once in the law that created them, and once the powers that be realized what that law had done, they went all the way up to the presidency to try and undo it. The NCAA objected to supporting women's sports, and searched for years to find a way out of that obligation. Even President Gerald R. Ford's office seemed concerned about those "women's organizations." Our country's perch atop global women's sports happened not because our leadership desired it, or even cared all that much about it, or held strong feelings about the place of women in society in general. It happened due to a collection of random factors all happening in a specific time and space.

That matters now because one of the many aspects of our federal government currently being torn apart includes the department that oversaw the law that made women's sports possible. Title IX, which once forced schools and universities to do everything from provide a girls soccer team to investigate reports of sexual harassment to provide fair pay, is being revised before our eyes, most prominently in the form of legislation endorsing state surveillance of women's bodies under the guise of "protecting" women from men in sports.

The reactionary movement behind this might be coming for vulnerable pieces of women's sports at the moment. But because of the tenuous foundation upon which officially sanctioned scholastic sports for women and girls was created, and because there is nothing in Title IX's original language that says women's sports specifically must exist, nothing is protecting women's sports as a whole from dismantling or destruction. What was created by accident can absolutely be undone by fiat.

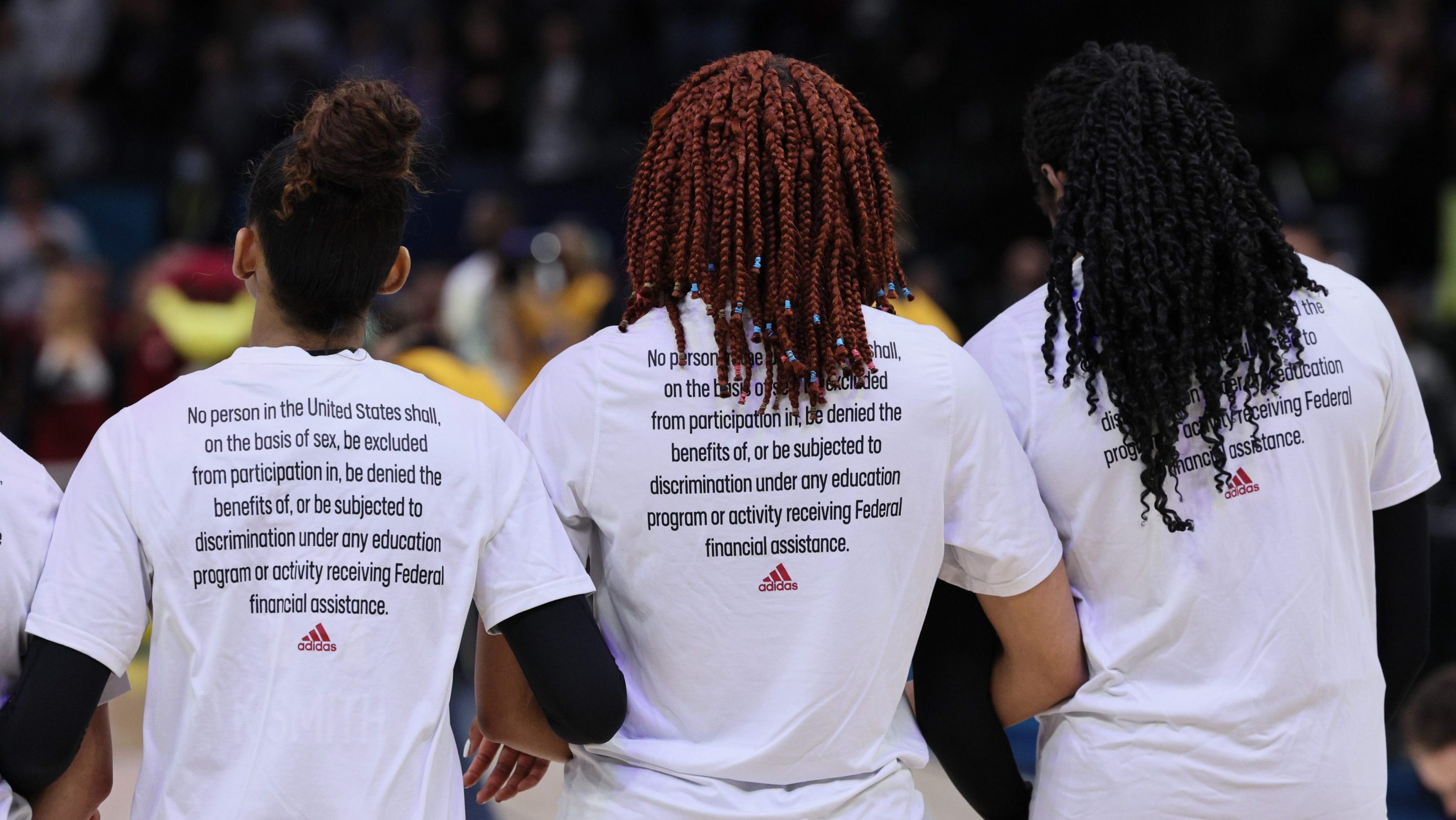

There is an entire history of women's sports that stretches back well over 100 years, and it intertwines with the creation and rise of modern sports itself. There's Dick, Kerr Ladies F.C. There's Babe Didrikson Zaharias. There's Alice Milliat. There's Louise Stokes and Tidye Pickett. How so many women were so systemically erased from popular history is a discussion for another day. What matters in our present moment is that for most people, recent women's sports history begins in the 1970s when Congress passed Title IX. The law is just 37 words: "No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance."

You will notice that this says nothing about sports.

Those who worked on it knew that Title IX had the power to open up women's sports; leaving it out of the text was very much a strategic move. It wasn't quite subterfuge, but the possibility sure was undersold. The first version, introduced by Rep. Edith Green of Oregon, made no mention of sports. Rep. Patsy Matsu Takemoto Mink of Hawaii, the first woman of color and woman of Asian ancestry elected to Congress, did not bring up sports when she testified in 1970 in the House of Representatives in support of the legislation. Over in the Senate, the office of Indiana Sen. Birch Bayh Jr. purposely downplayed how influential Title IX would be. Jay Berman, then the director of legislative affairs for Bayh, admitted as much to the Indianapolis Star in 2022, saying that doing so "would only work against us." A memorandum drafted years later for Ford would acknowledge this, saying the law passed "with little legislative history, debate or, I'm afraid, thought."

Title IX wasn't major news when it passed. The headlines came later, when people began asking what equal rights for women in education actually meant. In a country where sports is deeply embedded within academics—from physical education classes to team sports, from elementary school all the way through college, and with valuable scholarships in the mix—equal access to education necessarily meant equal access to sports. This immediately became controversial. When the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare proposed its regulations, which included physical education and more sports opportunities for women and girls, a Feb. 28, 1975 memo to President Ford said the proposal received more than 9,700 comments. The same memo said that athletics for women and girls was the topic that "raised the most public controversy and involves some of the most difficult policy and legal points."

Those comments about women's athletics, the memo reported, fell into three categories: Those filed by women's groups, those filed by women's athletic organizations, and those filed by colleges and men's athletic organizations. Groups like the National Organization for Women wanted women to have access to all sports, with separate women's teams only in those events in which women hadn't yet closed the performance gap. The Association

for Inter-Collegiate Athletics for Women wanted separate teams for women, with funding commensurate to that of men's teams, noting that it was opposed to the "'commercialism' of men's athletics and [wanted] to be allowed to use the money allocated for women to provide opportunities for more women instead of expending large sums for recruiting and scholarships."

The NCAA wanted none of the above, and argued that athletics was not covered by Title IX at all. It also asked that the revenue sports—football and men's basketball, mostly—be excluded from whatever the country's leadership was doing because they support all the other sports and schools "cannot afford to offer sports to women on the same scale as men." Ford even got a letter from the head football coach of his alma mater—Michigan, where Ford had played football decades earlier—warning him that the task ahead was "how to prevent the great injury to intercollegiate athletics, which imposition of these unreasonable rules will bring about."

There was one crucial problem with the NCAA's argument: The legal analysis done by the government couldn't find a way that athletics wouldn't be covered. This comes up again and again in the paperwork saved by the Ford Presidential Library: Yes, they heard the NCAA's complaints, but the law clearly said what it said. The only way to relieve schools and colleges from the duty of providing women's sports, that legislative analysis said, was for Congress to pass a law explicitly exempting all athletics. It never did.

Was that because so many members of Congress had realized the importance of equal rights and protections for women under the law, and how that had to include equal access to sports? That's doubtful. As a July 18, 1975, memo from domestic policy advisor Jim Cannon to Ford noted, trying to exempt athletics would raise the ire of women's groups. "The greatest likelihood," Cannon said, "is that we would displease many more people than we would please."

With Ford's approval, the regulations became official three days later.

The NCAA sued less than a year later, again arguing sports would not be covered by Title IX. In a statement, it said "the NCAA believes its members have the right, within their own community and through their own personnel and counsel, to determine their legal or other obligations with respect to the

provision of equality of opportunity, free from interference by the Federal bureaucracy." That same year, female rowers at Yale protested their lack of shower facilities by stripping naked in the office of the director of physical education. They wrote "Title IX" on their chests and their captain read aloud a statement saying, per the New York Times, "These are the bodies Yale is exploiting. On a day like today the ice freezes on this skin. Then we sit for half an hour as the ice melts and soaks through to meet the sweat that is soaking us from the inside."

The NCAA lawsuit failed, and the Yale protest worked. But the intermingling of Title IX with the federal bureaucracy continued. In 1979, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that people had the right to sue their school they felt that the institution had discriminated against them based on their sex. A year later, oversight of Title IX moved into the newly formed U.S. Department of Education. In 1994, Congress passed a law requiring colleges and universities that get federal aid money to give updates on their efforts to provide men and women's sports. When female athletes sued Brown University in the 1990s for eliminating the women's volleyball and gymnastics teams under Title IX, a court agreed with them.

"I think one of the best characterizations I’ve heard about Title IX is that it’s sort of like the guillotine out in the courtyard," Susan Ware, author of the book Title IX: A Brief History with Documents, told the Harvard Gazette in 2022. "It has an impact just because of its existence that is different from having complaints filed against the school and threatening to withdraw funds."

That we have women's sports, and so much women's sports, is in a sense because of federal bureaucracy—all its rules, all its management, and all those legal precedents. As Victoria Jackson and Andrés Martinez wrote in 2023 for New America about the U.S. Women's National Team's dominance in soccer, one of the most masculine-coded sports on the planet, "Title IX forced a level of investment in women’s sports without precedent in this or any other country."

That investment, and the dominance that it helped produce, is not because of the NCAA, which still doesn't support women's sports to the level that it supports men. A 2021 review of the men's and women's March Madness tournaments, done by a law firm commissioned by the NCAA, found that "with respect to women’s basketball, the NCAA has not lived up to its stated commitment to 'diversity, inclusion and gender equity among its student-athletes, coaches and administrators.'" That investigation also found that this was entirely the NCAA's own fault, because it had created a system "designed to maximize the value of and support to the Division I Men’s Basketball Championship." The impact of that was "cumulative, not only fostering skepticism and distrust about the sincerity of the NCAA’s commitment to gender equity, but also limiting the growth of women’s basketball and perpetuating a mistaken narrative that women’s basketball is destined to be a 'money loser' year after year.

"Nothing could be further from the truth," the report said. "The future for women’s sports in general, and women’s basketball in particular, is bright."

Republicans have campaigned against the U.S. Department of Education since its creation under President Jimmy Carter. Though any threat to completely dismantle it currently remains unlikely, if only because conservative power players benefit too much from some of its key programs, President Donald Trump's latest appointment to head up and ultimately wind down the agency is WWE co-founder Linda McMahon. As Josephine Riesman, author of the book Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of America, put it on the NPR podcast It's Been A Minute, "Linda has long been a master of this mask—this mask of, I'm a kindly grandmother who wants to be nice to you; I'll be a mother figure; I'm a good administrator; I run businesses well, when in reality, the fact is she's the hatchet woman and will do what Trump, who she's known since 1981, tells her to do." In case there were any doubts about McMahon's assignment, Trump told her, "Linda, I hope you do a great job and put yourself out of a job."

A day after being confirmed, McMahon put out a statement that talked about getting rid of "divisive DEI programs and gender ideology" within the Department of Education's purview. But that's what women's sports are—they exist because of a federal diversity program, and they are supported because of diversity mandates. Believing that women should have equal access to sports as men is, definitionally, a matter of gender ideology.

We are about to find out just how normalized women's sports has become, and how much American society really cares beyond the usual platitudes about equality and your daughter's local youth team. There will (probably) always be UConn women's basketball, North Carolina women's soccer, Nebraska women's volleyball, and UCLA women's gymnastics, just to name a few iconic programs. To their credit, they're just too important to their institutions—and, more importantly, the egos of those institutions' boosters—to let go. But that's always been just a sliver of the totality of women's sports in the United States.

Teams and entire athletic departments really can just disappear. It already happens on the generally much-better-funded men's side. In recent years, men's college gymnastics has fought to survive, multiple men's (and women's) tennis programs ended during the pandemic, and St. Francis College of Brooklyn closed its entire athletics department. Even the seemingly sacred high school football teams can shut down. Why can't more women's teams shut down, too?

More to the point, who is going to stop it? It's easy to cut things for "financial reasons" when no institution or law is making you keep them, no one from the party in power wants to make noise about it because it doesn't fit their talking points, and there are no reporters around to notice. The guillotine might still be in the courtyard, but how effective a deterrent would it be once the blade has been removed?

The NCAA has already said it won't defend trans girls and women. As the layers of the Department of Education are peeled away, and those that remain busy themselves with announcing investigations into school districts that support their trans athletes, it grows all too likely that there won't be enough people in the federal halls of power who care to use their power to keep as many women and girl's sports teams on the playing field as possible. That's leaving aside the threat presented by the Trump-appointed federal judges, past and future, who could reverse the legal precedents upon which Title IX's power rests for ideological reasons, or just on a whim. For decades, the security of women's sports has been taken for granted, both as a matter of settled law and as something as woven into the nation's cultural fabric as jazz, overstuffed deli sandwiches, and our very specific version of football. But all of that can be undone. One way or another, we are about to find out just how much our country really meant it when it promised all women and girls an education free from discrimination.

Know anything about what's going on inside the U.S. Department of Education? Please reach out! You can reach me directly using diana@defector.com or @dmoskovitz.99 on Signal. You can also use our tips inbox.