Defector has partnered with Baseball Prospectus to bring you a taste of their work. They write good shit that we think you’ll like. If you do like it, we encourage you to check out their site and subscribe.

This story was originally published at Baseball Prospectus on January 22.

A couple of decades back, during the glory days of New York drive-time sports radio, there were a couple of hosts who considered themselves baseball experts—don’t they all? On one long ago edition of their program, the chirping Stan of the pair served up various baseball luminaries, asking Ollie to rule on whether they were worthy of the Hall of Fame. Those with impressive career stats but lacking gaudy single-season numbers were dismissed with a single word: “Compiler.” Tommy John? “Compiler.” Bert Blyleven? “Compiler.” Don Sutton? “Compiler.”

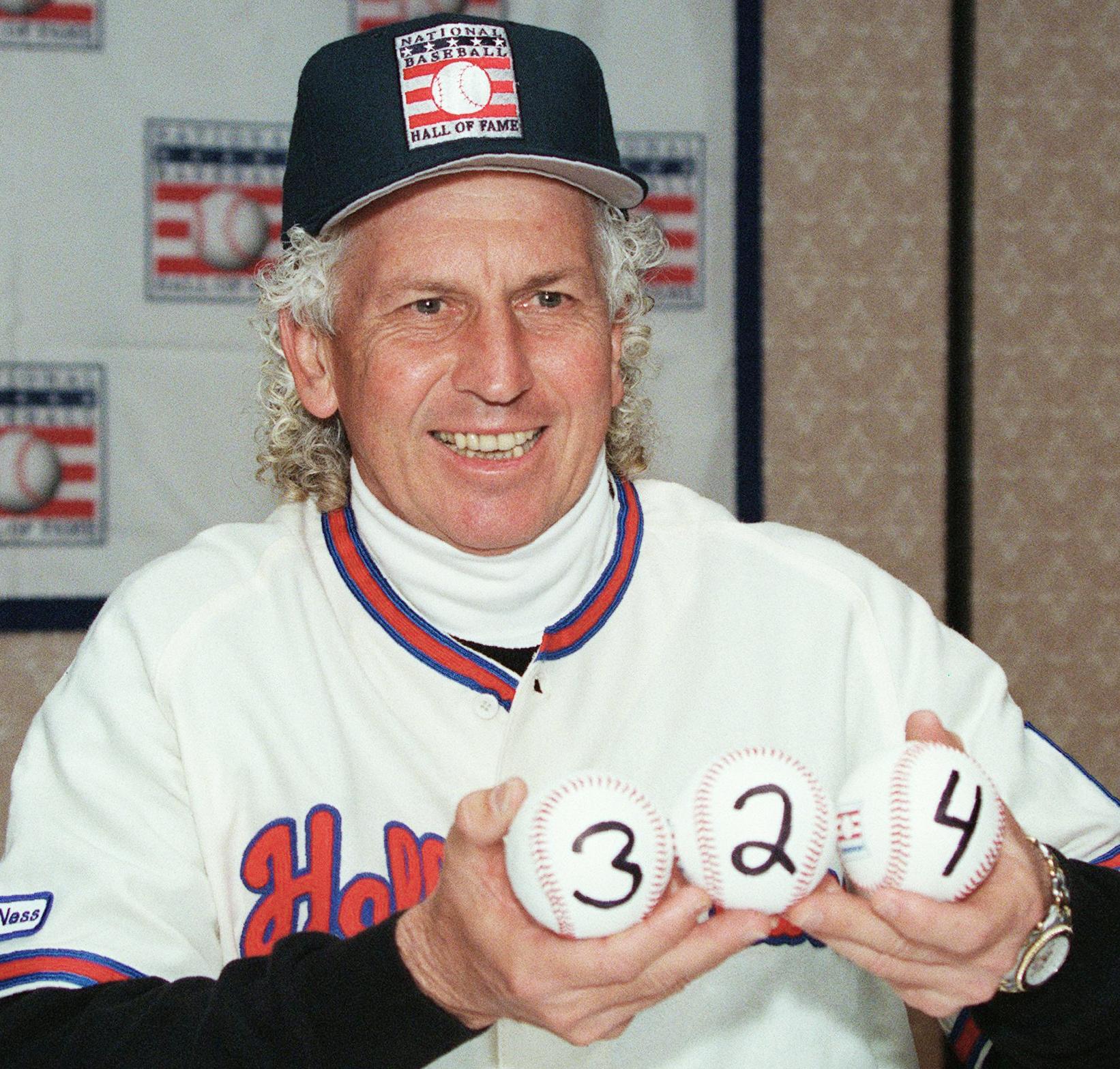

Sutton, who passed away on January 19 at the age of 75, was used to being slandered in this way; if one is going to embrace a pseudo-intellectual impossibility—that one can accumulate great career statistics without ever being great—then a 324-game winner with little black ink on his baseball card, one 20-win season, and no Cy Young Awards would seem like exhibit A.

It was what the proudly low-key Sutton, who had five career one-hitters and nine two-hitters but never a no-hitter, would have expected. In a 1978 article in Sport, Sutton said he was, “not a yelling, screaming headline grabber… I don’t need to be the most famous player in baseball. But it would be nice to know that I was respected and appreciated by those around me… Some day I’m going to retire with most of the Dodger pitching records and someone’s going to pick up the record book and say, ‘Gee, I never realized this Sutton was such a great pitcher.” He remains the Dodgers’ all-time leader in wins, innings, and strikeouts.

It must have been easy to miss him. Never flashy, Sutton was a four-pitch pitcher whose best offering was his curve and whose greatest tools were impeccable command, durability, and intelligence. “I try to put the ball over the plate,” he said late in his career. I’ve never been a [Dwight] Gooden or [Nolan] Ryan. It’s important for me to change speeds and put the ball where I want it.” When the Dodgers brought him up in 1966, he pitched behind Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale. The rookie went 12-12 with a 2.99 ERA over 225.2 innings, walking only 52 and striking out 209 for the team that won the pennant, yet failed to receive even a single vote in that fall’s Rookie of the Year balloting. The writers no doubt ignored him in part because of the excess weight placed on personal won-lost records at the time, but it was also easy to dismiss him as mere rotation-filler when Koufax set the standard at 27-9 with a 1.73 ERA and over 300 strikeouts. Sutton’s seeming status as a complementary pitcher continued in 1981 when he signed with the Houston Astros as a free agent and lined up behind Ryan, one of the most eye-catching pitchers of all time. “My fastball is like his changeup,” Sutton said upon signing.

Sutton’s extraordinary durability is attested to by his 20 consecutive seasons of well over 200 innings pitched, the truncated 1981 season notwithstanding (he pitched 158.2 frames that year). He retired as the all-time leader in games started among pitchers whose careers began after 1900 with 756 and was fourth in innings pitched. What makes his 5,282.1 innings pitched especially notable is that he earned them by showing up every four days rather than by going nine innings with each start. That represented calculation: Sutton was alone among his contemporaries in his willingness to admit when his team would be better off with a reliever in the game. Gaylord Perry completed 303 games, Steve Carlton 254, Tom Seaver 231. Sutton finished “only” 178. “I felt by staying out there I was jeopardizing our chances to win,” he said after a game in 1985. “I’m mature enough to know what I can do out there. When you’re young, the manager comes out and you tell him, ‘I can get ‘em, skip.’ But over the years you realize the bottom line is to do your job and help the team win the game.” He joked about discretion being the better part of his valor in beginning his Hall of Fame induction speech: “This is probably something that if it holds true to my career Rollie Fingers will do the last two parts of it.”

A dry wit, Sutton once deemed a start a success because he “didn’t hurt [myself] or anyone else.” What he might have hurt were baseballs—the accusation that he scuffed the ball were constant. “You’ll notice that the people accused of doing something to the ball,” he said, “are those of us with lesser ability who win more than we lose.” An artist with offspeed stuff—“He can make the ball talk,” said longtime Dodgers coach Monty Basgall—batters would often find the unusual movement he got suspicious.

If he did doctor the ball, he was an even better sleight of hand artist than he was a pitcher. “I’m the most accused and least convicted guy in the country,” he said in 1982. He was only “caught” once, on July 14, 1978 when he was going for career victory No. 200. Umpire Doug Harvey noted “a roughness of the ball in exactly the same spot [on] three balls” and ejected Sutton. However, at no point was Sutton seen committing the crime, and after the game he threatened to sue Harvey and the National League. That threat was never fulfilled, in part because NL president Chub Feeney decided to let Sutton off with a warning. “He also told me,” Sutton said, “as difficult as it is for me to do, to keep my mouth shut.”

The most celebrated occasion on which Sutton failed to keep his mouth shut was a 1978 interview in which he praised Reggie Smith as the Dodgers’ best player over Steve Garvey, remarks that led the two men to have a serious clubhouse scuffle. However, one of his best, simultaneously subtle and totally unsubtle examples of frank speaking came after he spurned a reported five-year contract offer from George Steinbrenner’s New York Yankees to sign with the Astros. “I just felt I would like to finish my career in a very happy, cordial, comfortable atmosphere where I don’t have the pressures of a New York City and maybe some other places.” In other words, Steinbrenner’s money wasn’t worth the aggravation of Steinbrenner himself. Some of Sutton’s former Dodgers teammates would have said he wasn’t worth the aggravation. For a man who once likened his mind to a series of rooms filled with logic, he sometimes failed to notice, or, more accurately, care how his self-possessed, blunt way of speaking might strike others as selfishness or conceit. “I would rather be honestly disliked,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1980, “than be liked dishonestly for being a phony.”

Sutton pitched for five postseason teams, including four pennant-winners, but never won a World Series despite some fine performances, including a four-hit shoutout against the Pittsburgh Pirates in the 1974 National League Championship Series. His greatest high-pressure start came not in the World Series, but on the last day of the 1982 season. Heading into the last series of the season, the Baltimore Orioles trailed the Milwaukee Brewers in the American League East race by three games with four to play. The schedule gods smiled blessed baseball with the two teams going head-to-head, and Earl Weaver’s team made things interesting by sweeping the first three games and tying the race heading into the last day. Weaver tabbed Jim Palmer to make the start. The Brewers, having traded for Sutton in late August to bolster a shaky rotation, matched one future Hall of Famer with another. The Brewers got out to an early 3-0 lead thanks in part to two solo home runs by eventual AL Most Valuable Player Robin Yount. Sutton was by no means sharp—he allowed a home run and walked five in eight innings, an uncharacteristically high total (his career rate was 2.3 walks per nine innings), but he never broke.

In the third inning, plate umpire Don Denkinger said, in Sutton’s words, “that somehow a mysteriously scuffed ball had gotten into the game. He asked me not to throw it if I found one. I asked him if I was supposed to play policeman and check all the balls. He said, no, he’d take of that, but he would certainly be happy if I didn’t find anymore. I said, ‘Me too, because they sure are hard to throw straight.’” In recent decades, baseball has seen all sorts of cheating mostly unimagined in Sutton’s day—performance-enhancing drugs and signal relays coordinated with video. Sutton’s scuffing seems quaint and innocent, less an effort to defraud the public and the competition than a skill, and one that provided an advantage that was as much psychological as it was actual.

“Compiler” is a word without real meaning. You can’t be good enough to play for 23 years without being good enough to play for 23 years. Mediocrities are not handed 756 starts. Maintaining a high level of quality for a couple of decades is as much an accomplishment as flaring like a supernova if the latter hurries on collapse and failure. We celebrated Tim Lincecum, Mark Prior, and Matt Harvey, but only for a moment. Don Sutton showed that there are other colors on the spectrum of greatness, that Neil Young had it exactly backwards: It’s better to fade away than to burn out. That’s why, even as he hit his late 30s and early 40s, pennant contenders competed to acquire him. He scouted batters and pitched to their weaknesses. The stuff may have been greatly diminished (his fastball was 85 on a good day by then) but 80-grade lightning still flashed in his mind.

As Young’s contemporary John Lennon wrote the same year Sutton reached the majors, “Living is easy with eyes closed, misunderstanding all you see.” To denigrate Sutton as lesser-than was to do exactly that. “I want to keep pitching until I embarrass myself on the mound,” he said when he was 35. He never did. His greatness was that he was right there in front of everyone all along.