They’d been waiting all winter for this, or perhaps for 39 years. On April 8, 1974, sports journalism’s most accomplished photographers descended on Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium for the Braves’ home opener against the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Time Inc. sent John G. Zimmerman, acclaimed for his innovative camera placement and lighting set-ups; the relentless Neil Leifer, famed for his unforgettable color photo of Muhammad Ali standing over Sonny Liston; Walter Iooss Jr., whose groundbreaking picture of Joe Namath by the pool before Super Bowl III launched a new style of celebrity-athlete portraiture; and the uber-talented Tony Triolo, credited with shooting more than 50 covers for Sports Illustrated during his career.

The Associated Press dispatched an experienced team that included Bob Daugherty from the Washington, D.C. bureau (taking time off from covering President Nixon); Joe Holloway, Jr., a veteran of the Civil Rights marches in the South; and New York–based Harry Harris, who’d been shooting since the 1930s.

They came to get The Shot: the defining image of Henry Aaron supplanting Babe Ruth as baseball’s home-run king. This was more than a sports story; a black ballplayer breaking the national pastime’s single most hallowed record represented a cultural milestone.

Before the game, as rain showers cleared, the photographers tested their remote-control cameras and staked out their positions: behind the plate, by the first- and third-base dugouts, high overhead.

But Harris went to the outfield. He climbed atop a makeshift platform that was situated on a narrow patch of grass between the left-field stands and a six-foot-high wire fence that stretched across the outfield.

To his immediate right was the Braves’ bullpen. Behind him was an advertisement for a bank card that read: “Think of it as Money.” Home plate was 400 feet away. He triple-checked his equipment. He waited.

Batting clean-up, Aaron walked in his first at-bat against Dodgers pitcher Al Downing. All 53,775 spectators stood as Aaron came up again in the fourth inning with Dusty Baker on deck. Ball one, and the boo-birds started. No one wanted to witness another walk.

Downing’s second pitch was a fastball that lingered over the plate. Aaron drove the ball high and deep toward left-center.

Harris was focused on his work: shooting every pitch of Aaron’s every at-bat. When he saw Aaron’s lashing swing through his viewfinder, and then heard the gigantic roar of the crowd filling the stadium, he knew that this might be the one.

He glanced up in time to see a white speck high in the Georgia night. The ball grew bigger as it descended speedily toward his perch.

Maybe he was going to shoot and catch No. 715.

Born in 1913, Harry Harris began working for the Associated Press at the age of 15, back when the flashbulb hadn’t yet been invented and the wire service airmailed its pictures. He started as a messenger, then learned the dark arts of the darkroom (processing film, making prints, writing captions). He taught himself how to be a photographer with the Graflex Speed Graphic, a camera that used 4x5 sheet film and was the preferred choice of newshounds.

According to one former colleague, the stocky-framed Harris was a “classic New York street-smart guy, always telling stories, straight out of central casting.” He soon graduated to staff photographer and shot his first World Series (the Cubs versus the Tigers) in 1935, the same year that Babe Ruth, playing out his career with the Boston Braves, hit his last home run, No. 714.

That same year, Harris was at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field when they played the very first night game in the Majors. He claimed that he was thrown out of the stadium because his flash disturbed the action. (At that time, the photographers actually worked on the field.)

His career was interrupted when he volunteered with the Signal Corps during World War II. He accompanied the U.S. 1st Army on their march across Europe in 1944–45 and photographed General Omar Bradley and General George S. Patton. His photos showed the devastating destruction suffered in the European theater; later, after Japan surrendered in 1945, he captured the raucous V-J Day celebration in Times Square.

He “owned” Yankee Stadium, according to Harold “Hal” Buell, the AP’s longtime executive news photography editor, and was a regular at spring training in the Florida Grapefruit circuit. Like every AP lensman, he didn’t exclusively stick to the sports beat. He covered murders, fires, political conventions, even a public hanging. He shot everyone from FDR to JFK to Fidel Castro to John Lewis; from Greta Garbo to Marilyn Monroe to ukulele-playing Tiny Tim.

But he relished sports for the “challenge to get a usable picture,” as he put it. Especially “when you compare sports with doing a presidential conference or some dirty old murder somewhere,” he told Buell and Catherine Scott in an AP oral history conducted in 1997.

In the postwar era, as camera, lens, film, and flash technology grew more sophisticated, Harris graduated from the Speed Graphic to the 70-millimeter Hulcher camera. Originally designed to take rapid-fire photos of rocket launches, the Hulcher gobbled up 100-foot rolls of film at 50 frames a second. Harris and other photographers adapted it for the press box because, before the advent of motor drives, the Hulcher allowed them to shoot sequential action frames. (The most famous examples: Frank Hurley’s series of Willie Mays hauling in Vic Wertz’s drive in the 1954 World Series.)

“In those days newspapers used to run a lot of sequence pictures in the sports pages,” Buell said. “Harry was a master of the Hulcher. You can’t beat experience.”

Along with contemporaries-cum-competitors like Hurley and Charles Hoff from the vaunted Daily News staff, Arthur Rickerby at UPI, and Henry Luce’s staff at Time and Life (and, later, Sports Illustrated), Harris was among those “who moved from the Big Bertha [a large-format camera manufactured by Graflex] and the speedy Hulcher and Speed Graphic cameras to the Rolleiflex and finally to 35 mm,” according to curator Gail Buckland, author of Who Shot Sports: A Photographic History, 1843 to the Present. (For those keeping score: Rickerby masterfully framed the last pitch of Don Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series.)

Harris’s sports pictures won numerous awards and were often published in the popular Best Sports Stories anthology (co-edited by Irving Marsh and Edward Ehre). Harris shot a youthful Jackie Robinson as he peered from the dugout at Ebbets Field before his first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, and he photographed the doleful Robinson confirming his retirement a decade later that’s as haunting a portrait as you’ll ever encounter.

On June 13, 1948, a little more than a year after Robinson’s debut, Harris traveled to the Bronx on a rainy Sunday. The Yankees were reuniting surviving members of the 1923 team to celebrate their 25th anniversary in the House That Ruth Built and to retire the Babe’s No. 3.

Ruth still owned every home-run mark, including the single-season mark of 60, set in 1927. Thirteen years after hitting his 714th homer, and dying from cancer, he was determined to give the Yankee faithful a final farewell in pinstripes. He needed help to get into his uniform in the locker-room and donned a topcoat to ward off the damp chill while waiting in the visiting team’s dugout. Finally came announcer Mel Allen’s introduction: “And now—George Herman “Babe” Ruth!”

“The Babe took a step and started slowly up the steps,” journalist-author W. C. Heinz wrote in The New York Sun. “He walked out into the flashing of flashbulbs, into the cauldron of sound he must know better than any other man.”

Harris snapped one photo of Ruth and his sepulchral smile when he emerged from the third-base dugout and the crowd stood to applaud him. Ruth then hobbled slowly toward home plate using a bat belonging to Cleveland Indians pitcher Bob Feller as a cane.

The band played “Auld Lang Syne” when Ruth took his curtain call. Harris positioned himself behind the frail slugger and from that angle snapped a moving picture. Visible are former and current Yankees (including Joe DiMaggio) as well as the stands and the trademark lattice facade of the stadium roof.

Next to Harris was Nat Fein, a staff photographer with the New York Herald-Tribune newspaper. Fein composed a nearly identical image to Harris's. Harris’s is the straight-no-chaser news photo; Fein’s is pure poetry and won the Pulitzer Prize—the first to be awarded to a sports photograph. (Ruth died two months after the ceremony at the age of 53.)

“Harry’s is a helluva picture of the Babe making his final bow,” said AP photographer Harry Cabluck, who occasionally worked with Harris. “It’s just not as famous as Nat Fein’s.”

According to Hal Buell, for some reason the AP did not enter Harris’s photo for the Pulitzer Prize. “That came up over the years,” Buell said. “Who knows what might’ve happened: Maybe they would’ve split the award.”

Ruth’s single-season home-run mark stood until 1961. The Yankees were rebounding from a soul-crushing defeat after Bill Mazeroski’s bottom-of-the-ninth, walk-off home run in Game 7 of the 1960 World Series. Yes, Harris was there for the jubilant welcome Mazeroski received at the plate.

Throughout the 1961 season, Harris covered the home-run explosion by the Yankees’ two sluggers, Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle. With Mantle hobbled late in the season, the only question left was whether Maris could beat Ruth’s 60. Critics hounded his effort, noting that he needed 162 games to outslug Ruth (who played a 154-game schedule). Maris’s hair started falling out from the pressure.

October 1, 1961, against the Boston Red Sox at Yankee Stadium, was the final game of the season. Harris brought his Hulcher and teamed with AP colleagues John Rooney and Murray Becker to cover every angle of Maris’s at-bats.

Only 23,154 spectators came to watch history. Maris flied out in the first inning against right-hander Tracy Stallard. But in the fourth, Maris drilled a 2-0 fastball into the lower right-field seats for Number 61. Harris used the Hulcher from overhead to capture Maris circuiting the bases.

The media attention and the toll of the chase weighed heavily on Maris. “After it was all over and done, Maris [was] in front of a bunch of writers in spring training,” Harris recalled. “He says, ‘There is Harris. He is one of the New York photographers, and photographers were the only ones I could get along with and have any feeling for. Writers, no; television, radio, no; photographers, yes.’”

Thirteen years later, it was Aaron’s turn to challenge the Babe. His effort to surpass Ruth’s career record had entered its final stages in 1973, when Aaron slugged 40 homers to end the season at 713.

After spring training, the AP sent Harris and several other photographers to follow Aaron until he broke the record. Thankfully, Harris’s wife knew the drill. “If [you] worked for AP especially, [you’d] be gone for a day, two, five, eight, and she understood everything,” Harris said. “If I’d come to the door, quite often she’d say the remark, ‘I remember you; you used to live here.’”

On Opening Day at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium, Aaron faced the Reds’ Jack Billingham. Harris shot the game from the outfield and didn’t have to wait long. On his first swing of the new season, Aaron hit number 714.

“It’s almost over,” Aaron said afterward.

Harris followed Aaron to Atlanta for the Braves’ home opener along with Daugherty, Holloway, and support staff to process the film, make prints, and send out the best photos over the wire to the 1,400 U.S. newspapers that subscribed to AP’s photograph service.

When Aaron came to the plate in the fourth inning, Harris took his post atop the scaffolding. He was shooting with a 35mm camera, a long lens supported by a tripod, and Tri-X black-and-white film. On the second pitch, Aaron took the bat off his shoulder for the first time that evening, and, suddenly, Dodgers left fielder Bill Buckner and center fielder Jim Wynn were racing back to the fence.

Harris realized that the ball was coming his way. He leaned over and tried to snatch it with his right hand, but he couldn’t extend far enough because he was holding the camera with his left hand. (He appears at around the :38 mark in this video.)

Instead, No. 715 settled into the glove of Braves relief pitcher Tom House. Fireworks shook the stadium as House raced toward home plate to present the historic ball to Aaron.

“It’s gone! It’s 715!” Braves’ radio announcer Milo Hamilton yelled. “There’s a new home run champion of all-time! And it’s Henry Aaron!”

House arrived at home to a beaming Aaron being mobbed by teammates and hugged by family members. When Aaron gripped what George Plimpton later described as “baseball’s greatest talisman,” he kicked off another competition between the photographers.

“It was messy,” Bob Daughtery said. “There was a lot of jostling, kind of a scramble. I don’t recall any fisticuffs.”

Daugherty’s black-and-white photo of Aaron raising high the ball he’d just walloped is a classic. So, too, Leifer’s color photo of Aaron with the ball, his cap askew and wearing a righteous grin, was the cover image in Sports Illustrated. (You can see Leifer in Daugherty’s photo; he’s just to Aaron’s left.)

SI photographers Tony Triolo and Walter Iooss Jr. both nailed the moment Aaron struck the ball from similar spots behind home plate. Their angle presented an almost panoramic tableau—there’s the scoreboard, the time on the clock (9:07), the stadium full of fans, even the ball—everything, that is, but Aaron’s face.

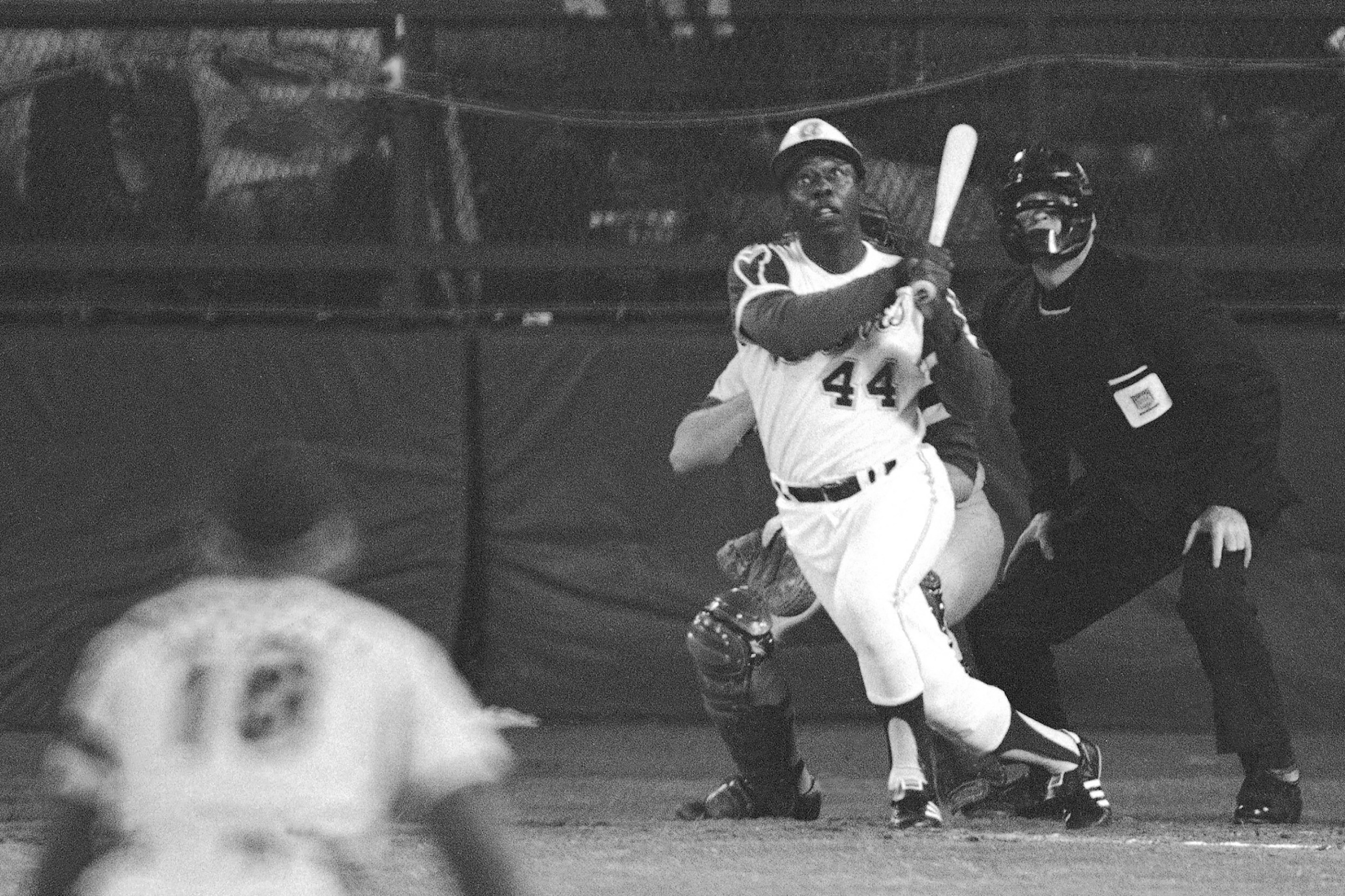

They’re all superb images, but it’s Harris’s straightforward black-and-white picture that resonates today. From nearly 400 feet distant he’s caught Aaron in the graceful arc of his follow-through, eyes and neck craning skyward, while umpire Dave “Satch” Davidson (behind catcher Joe Ferguson) tracks the ball’s flight and shortstop Bill Russell occupies the blurry foreground.

Its understated majesty reflects Aaron’s workmanlike styling, and you can sense the relief from Aaron’s mien; he knows that he got all of it, that this is the record-breaker, that his years-long journey to overtake Ruth and—perhaps—silence the racist abuse is over.

Leave it to Vin Scully to translate its import: “What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world.

“A black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol. And it is a great moment for all of us, and particularly for Henry Aaron, who was met at home plate, not only by every member of the Braves, but by his father and mother.”

Harris’s photo of Aaron’s 715 was published on the front page of the New York Daily News and in newspapers across the country. (Last month, it was reprinted in many of the obituaries that were published after Aaron’s death.) In the span of a quarter-century, Harris had completed a unique triple play connecting the home-run champs: Ruth to Maris to Aaron.

And then it was on to the next assignment. Later that year, Harris traveled to Zaire to shoot the Muhammad Ali-George Foreman championship fight. “That was the job,” Harry Cabluck said. “We just did it. We didn’t know it was history.”

Harris retired in 1978 after nearly 50 years with the AP. He died in 2002 at the age of 88.

In the oral history, he summed up his line of work: “People ask the same question many times. Many times. Do you really get paid to go to these ballgames and World Series and all? They pay you to go? And just the thought of it, I ... You never think of it while you're working. But as you look back, you have a ticket to the world. You go anywhere and do anything and on top of that, why, if you happen to come off with a good run of pictures there, you have a satisfaction that you can't get any other way.”