Defector has partnered with Baseball Prospectus to bring you a taste of their work. They write good shit that we think you’ll like. If you do like it, we encourage you to check out their site and subscribe.

This story was originally published at Baseball Prospectus on May 27.

A sigh. “Well, couple thoughts, and I’m sure you’re gonna have some questions, cause I’ve got my fair share of thoughts.”

Mike Shildt provided five minutes of thoughts about what had happened earlier, leading to the ejection first of Giovanny Gallegos’ hat and then, moments later, Shildt himself. Second base umpire Dan Bellino spotted a suspicious brown smudge on the brim as the reliever approached the mound. “This is baseball’s dirty little secret,” Shildt said in his postgame press conference, “and this is the wrong time, and the wrong arena, to expose it.” Yes, the cap probably had rosin and sunscreen on it over time. “Are these things that baseball really wants to crack down on? No, it is not. I know that completely firsthand from the commissioner’s office.”

Shildt went on to differentiate between his own pitchers using basic substances to help their grip and a certain other pitcher who shall not be named, who’s been publicizing his intention to add spin to his pitches via a co-owned company selling T-shirts that read “Legalize Pine Tar.” Shildt underlined that this was a tricky situation for the commissioner’s office:

“I know comfortably Major League Baseball is trying their best to do it in a manner that doesn’t create any black eye for the integrity of the game that we love. But speaking of integrity, how about the integrity of the pitchers who are doing it clean? … That’s who I’m speaking for. I’m speaking up for the hitters who have a living to make facing stuff that’s already really really good…”

It was never much of a secret, but it’s not a secret at all, now. Something has to be done. Everyone wants it; even the aforementioned unmentioned pitcher claimed he was publicizing the matter to force a resolution on it. Given the surprising honesty of Shildt’s speech—even as he admits there’s no guarantee that his own staff doesn’t dabble in the dark arts—has the feel of an inflection point.

There’s an old example of a collective action problem, a defense of government: A bunch of people live around a lake. If everyone pays to have their trash taken away, the lake is clean. If one person dumps their trash in the lake, the lake is still pretty clean, and the one person saves money. If everyone dumps their trash in their lake, they share a rotten lake. Now imagine that the people are scored by how much money they have, that they need to find every competitive edge possible, and it’s not looking good for anyone. That’s why you need someone in charge to make the risk of getting caught bad enough to remove the incentive. It’s why you need leadership.

Baseball very badly needs leadership. Shildt is willing to risk a disincentive of his own, in the form of a fine, to say so. But it’s not so easy. Doctoring the ball is a tradition as old as the game itself, and the sport has a rich history of turning a blind eye.

Watching old recordings of baseball can feel a little like reading Chaucer; it can take some effort wading through all the thynes and myriges, but if you can push through that you’ll be rewarded with something that feels strikingly modern. The cadence may feel just a little off, but the rhythm of thirty-year-old baseball still feels like baseball: The same slow wave of the bat before the pitch, the same cliches of the broadcast team, the same green grass (or grasslike material). Close your eyes and listen, and you could be anywhere, anytime.

And then occasionally something will come along and destroy that illusion.

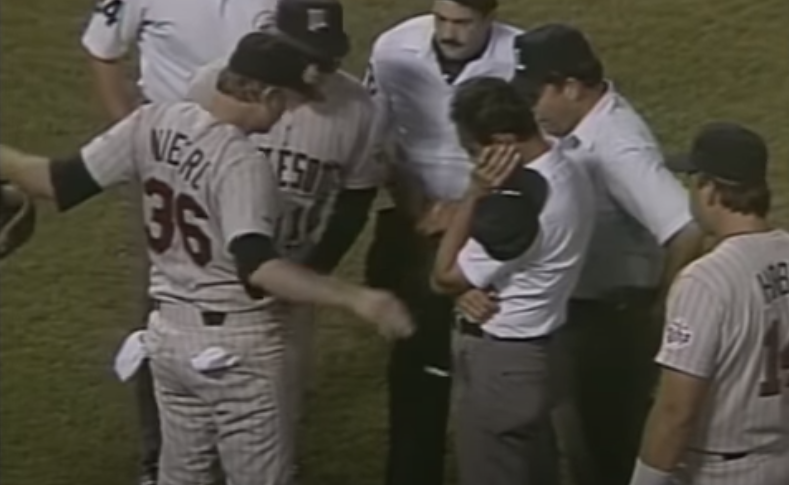

On August 3, 1987, veteran knuckleballer Joe Niekro threw a particularly wicked pitch to Brian Downing for a strike. Home plate umpire Tim Tschida called for the ball, which Niekro weakly tossed to the ground; afterward he asked for the pitcher’s glove. Manager Tom Kelly moved to intercede, but even then, he and his pitcher were outnumbered, as all four umpires converged and demanded that Niekro empty his pockets. The pitcher obliged, throwing his arms up in a gesture of innocence, and tossing an emery board out in the process. It was not subtle. Niekro was ejected, and suspended 10 games for scuffing the ball.

The joke, of course, was that Niekro’s secret wasn’t a secret at all; everyone knew the 42-year-old was doctoring the ball. He even went on Letterman wearing a tool belt, but he maintained his story: the emery board was for maintaining a knuckleballer’s precious fingernails, the sandpaper for blisters. This came half a decade after the retirement of the greatest public cheater in baseball history, Gaylord Perry, though the 1980s were rife with accusations of ball-scuffing, from Mike Scott to Tommy John to Don Sutton. Only Niekro got punished; the only rule is that you can only break the rules so much. At least, that used to be the rule.

The story begins again on April 10, 2014. Michael Pineda is ahead on Grady Sizemore 1-2 when Red Sox manager John Farrell emerges from the bullpen to talk to home plate umpire Gerry Davis. It is, largely, the same performance, 27 years later. Derek Jeter plays the part of Tom Kelly, grinning in disbelief at the slander of his teammate. Davis checks his glove, his palms, then asks him to turn around; the pine tar glints for the camera like a clumsy bit of foreshadowing. The umpire pulls off a glove with his teeth, touches Pineda’s neck, and puts an end to his evening.

Like Niekro, Pineda got ten games, though it proved far worse, as the pitcher injured himself in a simulated game and wound up losing four months. What’s interesting, though, is the narration supplied by Al Leiter at the 2:00 mark of the video:

“I think the reason why, Michael, the reluctance of John Farrell or anybody else is that many pitchers use something periodically through their career—I’m not saying every game—to get a better grip. And I still don’t understand that rule as to why that’s a bad thing for the pitcher to have a better grip. We’re not talking about altering the flight or the integrity of the pitch based on something that’ll enable the pitcher to have the ball slip out of his hand.”

This quote isn’t presented to call Leiter out, but to demonstrate that this was indeed what everyone believed at the time. Pine tar wasn’t like spitting or scuffing. It was good for batters! Every pitcher should use it. But, you know, be subtle, because it’s technically still illegal.

Seven short years later, everyone is still using pine tar and similar substances, but it’s not out of altruism for the batter. The high speed cameras of Statcast provided numbers for the spin rate of pitches, and analysts, both independent and extremely dependent, did research to the benefits. The conclusion: Pine tar absolutely does alter the flight of the pitch, in ways far more beneficial and controllable to the pitcher. We couldn’t have known then, except the small fraction of the we who was actually doing the pitching and feeling the difference, but we do know now. And especially after Trevor Bauer took his results public, and hitters have reached new lows in their ability to make contact, pressure has mounted for Rob Manfred and MLB to enforce, grudgingly, its own rules.

As Stephanie Springer pointed out in April, however, it’s not that easy. It’s one thing to say that a ball should not be doctored. It’s a very difficult and much more nebulous thing to say what a doctored ball actually is. Not only is it a question of gradients, but a question of exactly what to look for, given that newer, subtler, and more effective substances are widely available. MLB’s plan is to attack cheating from the opposite direction, looking at spin rate numbers looking for aberrations and targeting would-be cheaters that way, rather than at the scene of the crime. Russell Carleton supplied the mathematical means for detecting such spikes in spin rate, and the numbers are appropriately gory. So far in 2021, they haven’t nabbed anyone.

But when they do, a host of other problems immediately present themselves, many in the form of repeated history. Baseballs go through a rigorous preparation process, and are stored by the home team prior to the game. A player caught cheating in retrospect can easily transfer suspicion onto some random clubhouse attendant somewhere in that preparation process, just as was the case for Ryan Braun, as well as the excruciating “deflategate” scandal involving Tom Brady and the PSI of footballs. If MLB is really intent on punishing players for their results, they’d have to take control of every variable outside the pitch, which means controlling and securing the supply of the baseballs themselves.

But no matter how closed a system might be in design, there are always cracks. The saga of Ryan Braun reminds one how far a player can go to erode the legitimacy of test results. The best method for catching a cheater remains the old-fashioned one: to actually catch them cheating. It’s kind of amazing, even watching the clumsy attempts of Niekro and Pineda, that pitchers can cheat at all; they’re right there, in the direct center of tens of thousands of witnesses, the constant focus of the unblinking eye of the camera. It’s not hard, after a few innings, to notice the patterns in their between-pitch habits.

The story begins again on May 26, 2021. The White Sox have the go-ahead run aboard in the bottom of the seventh when Giovanny Gallegos is summoned in for relief. Before the warmups are done, Joe West, fresh off his record-setting appearance, is out at the mound with a polite request.

Cardinals manager Mike Shildt politely declines, and is summarily ejected. Eventually a tarless cap is delivered to the reliever, who proceeds to strike out two batters to hold the lead. (Of note is the fact that Gallegos’ fastball spin rate was down 30 rpm from his average—not a drastic amount, but a slight downtick—after the change was made.)

The ultimate question to all this is whether anyone in the league office actually cares. Even without the theoretical benefits of the sticky baseball—HBPs are up, though this is actually a result of the batters and not the pitchers—Manfred is forced to decide whether the cost of enforcing the rule is worth the cost of its current level of flaunting. While Bauer’s social media presence may have inspired the original shake of the finger, the Year of the No-Hitter may be what actually provides the pressure to do something, and something less violent than changing the shape of the field, to curb pitcher dominance.

On the Cardinals broadcast, the usual refrain arose: Why bother Gallegos when everyone is doing it? But of course this is a fallacy, since it’s impossible for everyone to be doing it, only the pitchers. It’s also a mentality that lies in direct contradiction to the entire steroid era, where the defense of “everyone else is doing it” proved worthless in the court of public (and league) opinion. If the rules don’t matter, you can’t rely on them next time you do need them to matter. Baseball is a beautiful sport, but it’s not that original. Every form of cheating has been performed at some point before, and each time, someone has gotten away with it. The Astros could just point to the 1951 Giants, after all. “A rule wasn’t enforced once and therefore it can never be enforced again” is not a legal or ethical foundation for anything.

This is not to say that the sticky grip phenomenon is identical to steroids. It’s not. They’re both rooted in the same problem, a prisoner’s dilemma, in which every player gets trapped into thinking that everyone else really is doing it, and that they’re punished on the field for not following along. But injecting a steroid is a definitive, premeditated act: you can’t half-shoot a needle, the way you can apply that pine tar in degrees.

The same is true of executive power. It was easy, and probably logical, to treat the scattered rumors as aberrations, the odd ejection as a misstep of the clumsy or desperate. But gradually, like the light past sunset, the situation has darkened.

Rules need to be enforced, and they need to be enforceable. If they fail in either sense, they should not be rules. This is where the sport needs firm leadership, to determine what’s best for the game and execute on that determination universally and fairly. And if it can’t be done, strike it from the book, and devise another solution that pushes the balance back toward the hitters. Stop the cheating, or stop calling it cheating. We, and the players themselves, should be allowed to know.