On April 8, millions across North America will witness day suddenly become night for a few brief, wondrous minutes during a total solar eclipse. The astronomical event is essentially a cosmic photobomb: It occurs when the Moon completely covers the Sun and casts its shadow over Earth.

The eclipse’s path will dash northeast across the country, shrouding portions of Texas, Maine, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois, Kentucky, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine in midday gloom. The exact time of the eclipse varies depending on where you are along that path, but it’ll happen in the early afternoon. During the time of totality, you’ll be able to gaze at stars and planets, namely Jupiter and Venus, and even comet 12P/Pons-Brook in the darkened sky. What’s more, the eclipse will also cause a noticeable drop in temperatures and allow us to witness how animals react as darkness unexpectedly falls.

It’s no wonder that over the millennia, before humans developed a thorough scientific explanation, many believed eclipses to be omens. Though solar eclipses are no longer mysterious, sketching their influence on humanity reveals the powerful cultural footprint they’ve left behind.

“We've been watching the heavens for millennia,” says Angela Speck, chair of physics and astronomy at the University of Texas at San Antonio, and a veteran of three eclipses. Though many cultures were able to predict them accurately, “how they react to it is going to vary,” Speck adds.

Some of the earliest solar eclipse records come from around 770 BCE in China, where they were interpreted as a celestial dragon devouring the Sun. In response, people banged drums and yelled to drive off the dragon. The Inca of South America believed in an almighty Sun god called Inti; to them, solar eclipses were a sign of Inti’s wrath and displeasure. Some merited human sacrifices to win back the god's favor.

Solar eclipses have shaped the course of history: In the 6th century BCE, an eclipse in Greece ended a six-year war. According to the historian Herodotus, it was during a conflict involving the Medes and the Lydians. When the heavens darkened over the battlefield, which had been foretold by Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus, men ceased fighting and were anxious to get on peaceful terms.

Is there a scientific basis for humanity’s long fear of eclipses? Speck believes that the need to protect your eyes during a solar eclipse may inadvertently reinforce ideas about its dangers. “You shouldn't be staring at this because it's going to damage your eyes, but that translates into ‘this is dangerous and you need to hide from it,’” Speck says. “You can understand how it's evolved to where it is.”

To view an eclipse, scientists before the 20th century looked at it indirectly via its shadow or through rudimentary devices, like a pinhole camera or smoked glass. Off-the-shelf eclipse viewers—glasses with protective film covering the eyeholes—gained popularity in the early 20th century with products like the “Eclipse-o-scope,” according to an article from the Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Total solar eclipses have long held additional significance for many Indigenous communities. Cody Cly, a doctoral student from the University of Texas at San Antonio, tells me that the Navajo or Diné people viewed eclipses as a time of renewal. For generations, the Diné have studied the sky and passed down tribal stories. “All we could do back in the day was observe,” Cly says. They say Jóhonaa’éí, or the Sun, is a male being and the Tł‘éhonaa’éí, or the Moon, is a female being. “They're very sacred celestial objects in our sky,” Cly adds.

Traditionally, the Diné do not look at eclipses. “At that moment, when the Sun and the Moon are doing their little dance—or just eclipsing—we take that time to plan ahead for the future, spend time with family, and pray,” Cly says.

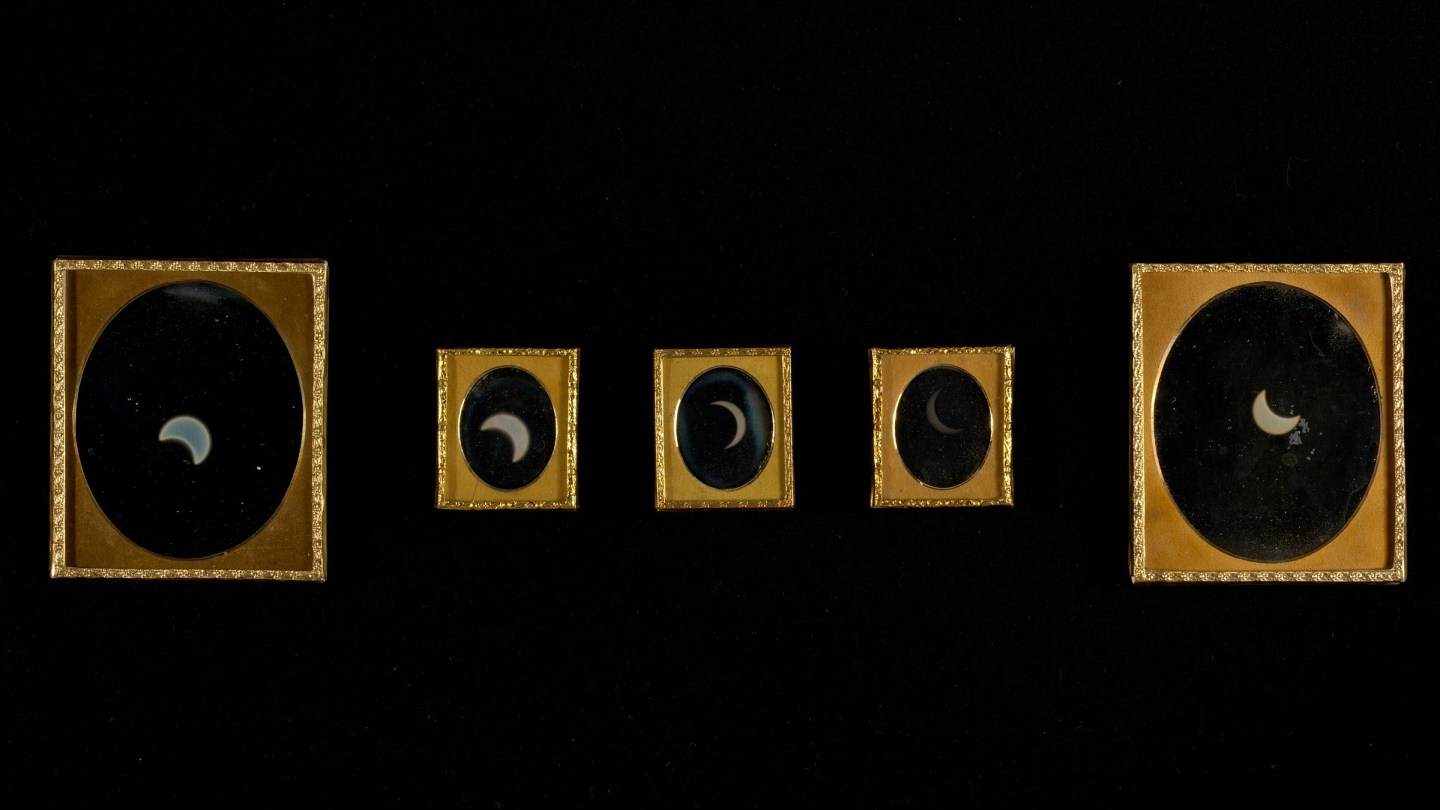

Before the 19th century, eclipse observations were largely descriptive and relied on artists to record the eerie sight. With the advent of photography, scientists were able to document the full visual and atmospheric aspects of that fleeting phenomenon. With improved prediction, scientists were able to begin chasing the daytime shadow of the Moon.

In 1878, Thomas Edison supposedly traveled to Wyoming, along the thin path of totality, to test out a new heat-sensitive invention that studies the Sun’s corona—the wispy plasma that surrounds all stars, but could not be observed directly except during an eclipse. He set up his device in a chicken coop on a hotel property, the perfect place for it: cool, dark, and quiet. Alas, he did not consider the chickens’ instinctual reaction to the darkness—they rushed back into the coop and upset his experiments, or so the story goes.

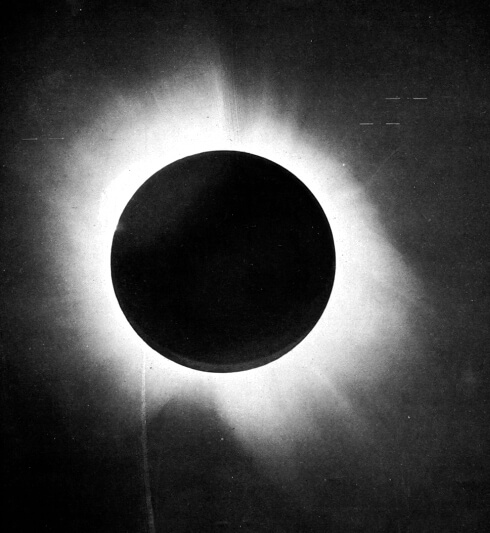

Over years of experiments conducted in the rare moments when our Moon blankets the Sun, we’ve gained a treasure trove of scientific insights about the wider universe. In 1919, English astronomer Arthur Stanley Eddington put Einstein’s then-four-year-old Theory of General Relativity to its first major test. Eddington led an expedition to the island of Príncipe off the west coast of Africa to photograph the total solar eclipse, which showed conclusively that the Sun’s gravity bent starlight around it. “That eclipse changed the world,” says Dr. Ed Krupp, director of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles.

Today, the orbital mechanics that result in eclipses are clear and unmysterious. Still, Krupp says it’s easy to get bit by the eclipse-chasing bug. “Most people who haven't seen a total solar eclipse before will experience an insatiable desire to go to the next one,” says Krupp, who has seen over a dozen solar eclipses and is gearing up to see April’s from Mazatlán, Mexico. “They're probably one of the most engaging and mesmerizing experiences that anyone can have with the sky. It is intense. It is short. It has drama. As soon as they've seen one, they're converted.”

Chasing eclipses is not limited to scientists; these events are also massive tourism draws. According to estimates from The Great American Eclipse, millions will be traveling to catch a glimpse of this one. Texas, one of the states smack dab in the eclipse’s path, is preparing for an onslaught of up to 1.08 million tourists.

“I’m glad we have [eclipses] because it reminds us of that sudden chill,” Ann Druyan, award-winning writer and widow of America’s foremost ambassador to space, Carl Sagan, said in a Time Magazine interview. “The motion of the birds, the way that the rest of life reacts to the blocking out of the Sun. It has that kind of mythic, biblical power to it. And it should.”

The alignment of celestial bodies during April’s solar eclipse will serve as another reminder of the clockwork of the universe. Humans across the millennia have gazed at the same awesome sight—the same Sun, the same Moon. It can be humbling: we can in no way affect or stop it. But because we can predict it, you may want to make plans to catch April’s eclipse. If you don’t, the next total solar eclipse visible from any point in the contiguous United States will occur in 2044.