In 1973, only five years after releasing Night of the Living Dead, George A. Romero was, in the eyes of the movie industry, washed up. Night was already well on its way from revolting little horror movie to hipster favorite to cult classic to actual classic. But no one saw much money from it—even though, it should be pointed out, it was still playing on the Midnight Movie circuit in 1973. And after failing to replicate Night’s success with subsequent efforts, Romero’s filmmaking troupe split, burdened by debts and frustrated by the mounting difficulties of raising money for another movie.

Romero was on his own for the first time in his career. He was in Pittsburgh, about as far as you can get from Hollywood, and he wanted to work. He wanted to keep making movies. He and his collaborators had built a very successful business making commercials, mostly for local companies. (Romero also directed a few shorts for local children’s TV host Fred Rogers, including the immortal Mister Rogers Gets a Tonsillectomy, and branched out a few times into more national concerns, including a high-profile campaign film for Lenore Romney’s unsuccessful 1970 Senate run—any footage you saw of young Mitt during his presidential run was likely filmed by Romero.) Ads were a way to pay the bills and buy cameras and lights and such; shooting them was also the closest thing to film school Romero’s crew could find in Pittsburgh. They made rent while teaching themselves the equipment, developing their style, and making the sort of connections that would be useful in raising money for low-budget features. But by 1973 Romero was past that. All through his tenure as a commercial director he had been trying to get features off the ground, and with Night, he’d finally succeeded. He wasn’t above this sort of work for hire, but he’d done enough of it for a lifetime.

It was during this desperate period that he hit it off with a video producer who interviewed him for an industry magazine. In the 1970s, “video” meant a lot of things but, most urgently for Romero, it meant TV. The TV landscape of the era was mostly regional and decentralized, with national network programming making up a relatively small percentage of airtime, even on local affiliates. An enterprising producer could package stuff together and sell tapes all over the country to stations looking to fill out their Saturday afternoons or whatever. It wasn’t Hollywood money, but it could be Pittsburgh money, for sure.

Romero and his new producer were, essentially, starting over. They had equipment and expertise and not much money. What did they have? Well, they had Pittsburgh. Not the sunniest place in the 1970s. Its economic base was hollowed out by the collapse of the steel industry and the city and environs would take decades to recover. But it did have the Steelers and the Pirates, and a shocking number of elite athletes from and in the city. A lot of them were hugely compelling personalities, beloved by locals and by the rest of the country. Franco Harris! Willie Stargell! Bruno Sammartino! Mean Joe Greene!

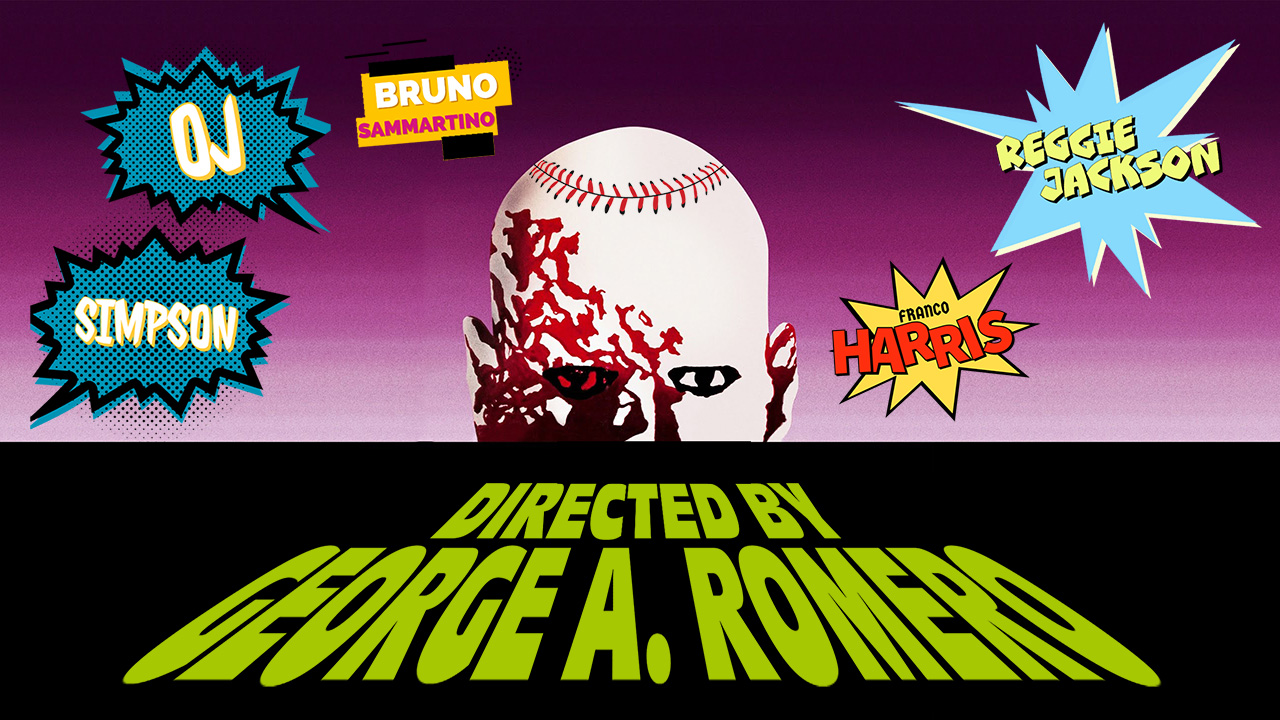

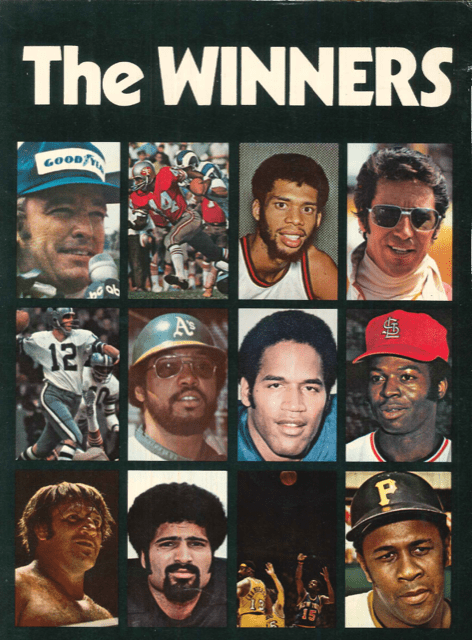

Thus, in '73 "The Winners" was born: Romero would direct and/or produce profiles of athletes, mostly Pittsburghers but quickly branching out into whatever athletes they could get to sign up—which is how Romero’s infamous O.J. Simpson profile came to be. Romero would spend most of the next three years on "The Winners"—not exactly a TV series but rather a package of films, a bunch of 50-odd-minute documentaries that could be bought individually or together by local TV stations who could then broadcast them whenever and however they wanted. It’s basically impossible to figure out exactly how widely these were seen, though they do seem to have showed up as in-flight entertainment for TWA a few years later, and probably were in circulation on cable in the early days of ESPN. Romero’s O.J. profile was released on home video during Simpson’s trial, though I’m not sure who would have owned the rights to it at that point. (The O.J. doc was released on DVD, sorta, as a hidden Easter Egg on the DVD for the justly forgotten softcore film The Bare Wench Project.) Some of the docs have popped up on YouTube or Archive.org, and there was a not-quite-official DVD box set of the Steelers movies in the early aughts, but several "Winners" films seem either lost or hopelessly obscured by the dueling copyright hells of indie film production and footage from professional sports leagues.

"The Winners" is now a bit of trivia known mostly by committed horror enthusiasts. It’s unclear how to watch all of the docs, lawfully or at all—and, to generalize wildly, the population of George Romero fans passionate enough to know of his obscure hourlong Reggie Jackson documentary may not actually include many people who are also passionate enough about Reggie Jackson to want to watch a nearly 50-year-old hourlong TV documentary about him. But here’s the thing about them: They’re fantastic.

A defining characteristic of feature films as a medium is that they are outrageously expensive to make. And not just the ones where recognizable stars shoot laser beams from their hands. It’s true that anybody can now shoot a movie on their cell phone and upload it to YouTube, but if you’re looking to get a feature into theaters, it’s gonna cost a lot of money.

This means you either have to figure out a way to work within a system that requires a host of executives and financiers to approve of your ideas, or you have to raise the money yourself. Working with the studios requires, first and foremost, their attention, but then after that it requires a filmmaker to convince them that an idea will be profitable.

Raising the money yourself is prohibitively difficult for anyone without at least a foot in the door already, and I don’t think it’s too terribly broad an assertion to say that most creative types are extremely bad at it. Or, at least, that skill in raising money is totally separate from the skill of making art. The best path into indie filmmaking is to have a lot of money already; the next-best is to somehow cobble together a production from spare film, borrowed equipment, and volunteer cast and crew, and have that debut become a hit. And it’s got to be a hit, because you can’t ask people to work for free a second time.

In terms of profit, impact, and longevity, George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead has a strong claim to being the most successful debut feature ever made. A low-budget horror movie made by a tight-knit group of filmmakers in Pittsburgh, it scored decent enough box-office following its 1968 release, but as a low-budget violent horror movie was despised or dismissed by whatever mainstream critics were forced to review it. A host of these, most famously Roger Ebert, were sent reeling for their fainting couches at the sight of the undead fighting over entrails. Other critics scoffed at the film’s provenance, as it came not from the outskirts of Hollywood or from a small but vital indie scene in New York City, but from “some people in Pittsburgh,” of all places.

But then Night just stuck around. The distributor re-released it a year later on a double bill with Slaves, a film starring Ossie Davis and Dionne Warwick made by old-school lefty Herbert Biberman (Salt of the Earth). That brought new crowds, who saw what Ebert and the New York Times did not: a black hero pitted against an obnoxious white patriarch who he eventually shoots in the gut, only to become the victim of a seemingly unwitting all-white posse that mistakes him for a zombie—or can't be bothered to suss out the difference. Hip types soon found it and noticed that it had Politics, but also that it was astonishingly well-made, beautifully photographed in a style that’s something like verité Expressionism: largely handheld camerawork favoring sharp angles and severe lighting. It found a home on the nascent Midnight Movies circuit but also among the highest of high-art venues, eventually playing at the MOMA in a series also featuring work by avant-garde legends like Jonas Mekas. It also made its way onto television, and only a few years after it sent delicate critics into conniptions, Night had made its way into the homes of millions of Americans on a semi-regular basis as useful filler for stations looking to round out their late-night schedules.

The problem, as any horror fan knows, is that Romero and his collaborators made next to no money from the movie, as distributor negligence left Night in the public domain. A last-minute title change imposed by the distributor from Night of the Flesh Eaters (Romero was always absolutely terrible at coming up with titles, see also “The Winners”) to the far, far superior title Night of the Living Dead came without also importing the little copyright symbol, a tiny-seeming oversight which doomed the thing to endless replays and re-releases without any of the profits filtering back to the producers. The thing is, that wasn’t wholly unheard of at the time: Before home video, copyright only really mattered for a tiny number of films thought of as classics—think Gone with the Wind or King Kong—that would be re-released every few years in perpetuity. On initial release, prints were controlled by the distributors, and a gory low-budget horror movie seemed unlikely to become a perennial favorite. Night’s influence is, of course, completely tied up in its free availability—that’s why it stayed on the Midnight circuit for so long, why it became a go-to filler for theater owners or station managers who needed something to show, why the VHS became ubiquitous in the ‘80s, and why so many filmmakers felt free to rip it off. Criterion put out a high-quality restoration a few years ago, but of course Night has been uploaded to YouTube dozens of times. In fact, when you finish reading this story, why not scroll back up here and watch it?

The distributor’s far more damaging sin was withholding the profits from Night's initial release. Romero would win the battle but lose the war: The filmmakers won a lawsuit ordering the distributor to pay up, to which the distributor responded by promptly declaring bankruptcy. So, although Romero and pals made a couple more pretty great movies (Season of the Witch and The Crazies), debts piled up, and the group that had been making movies together since college split.

Romero’s career lasted another three decades, and he made several more films that attained the status of “cult classic,” none of them financial hits. His final three movies were “Dead” movies—Land of the Dead, Diary of the Dead, Survival of the Dead. He was, and is, the Zombie Guy, who invented the modern zombie and made a bunch of zombie movies, and by the end of his career that was all he was making.

But, really, it’s more that zombie movies are all he could get funded. He and his friends had spent nearly a decade trying to make a feature before they started filming Night. They built a successful career for themselves making commercials and spots for TV to raise money and buy equipment and develop the kinds of skills they’d need to make a feature. But their ideas were mostly pretty arty—Ingmar Bergman films and Orson Welles’s Shakespeare adaptations were the operative inspirations for their unmade mid-1960s project Whine of the Faun (remember what I said about titles?). They turned to horror because they thought, correctly, that they had a chance at finding funding and distribution for a low-budget horror movie. And Romero brought an arthouse stylishness—severe angles, handheld camerawork, stark lighting, lots and lots of existential dread—to what any normal person seeing the title Night of the Living Dead on a marquee would assume to be a run-of-the-mill horror movie. It never occurred to Romero that he would be tethering himself to horror for the rest of his life. That he would be the Zombie Guy. He was always careful not to say anything too critical of the genre that might upset his fans, but the fact was that horror was a “prison” that he could never fully escape.

For "The Winners," Romero started with Franco Harris, the Steelers’ likable young running back. But before he could finish the editing of Franco Harris: Good Luck on Sunday, he got an opportunity to film the most popular, most beloved athlete in the country. O.J. Simpson: Juice on the Loose was broadcast nationally—the sole “Winners” doc to receive a national network spot—on a Saturday afternoon in late December, 1974. It would be the most conventional film in the series, and the least compelling. Simpson is the most polished and practiced of Romero’s subjects, and the movie never penetrates beyond the smile and the charm. A lot of the running time is given over to Simpson’s teammates and Howard Cosell and the like talking about Simpson’s career. It’s the one that’s the most about on-field exploits, and Simpson adamantly refuses to reflect on any of it.

At the margins, though, Romero found ways to make it weird and interesting. He edits the football into almost abstract montage sequences—including the one that opens the movie, scored to a funk version of Thus Spake Zarathustra. (Romero was a big Kubrick fan.)

At one point, Simpson muses about his charitable work “with youth groups” but that he’s “gonna have to do something a little more for me, you know, as an individual, whether that’s TV or movies or something that I’ll be able to get rid of those energies that I have.” And a shot of Simpson answering the phone quickly devolves into a hypnotic Steve Reich tape loop of him repeating “Juice here, go,” which then turns into a high-energy musical montage of still photographs that ends with Simpson’s print ad for RC Cola.

Romero wouldn’t have to work quite so hard to make his other subjects interesting. They finished Good Luck on Sunday next, then made somewhere around a dozen more. In addition to the Harris and Simpson docs, Romero would direct Bruno Sammartino: Strong Man, Reggie Jackson: One Man Wild Bunch, and Willie Stargell: What If I Didn’t Play Baseball, as well as docs on Indycar driver Johnny Rutherford and golfer Tom Weiskopf, and something called NFL Films: The 27th Team. His collaborators directed docs on the Steel Curtain, Lou Brock, Mario Andretti, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Rocky Bleier, and Terry Bradshaw.

It is exceedingly strange that "The Winners" exists at all, not least because Romero was never much of a sports fan. And it shows. The typical sports documentary might take an athlete’s career as a rough structuring principle: interviews and clips touching on key points in a life and a career, or maybe the ups and downs of a single season. But sports qua sports take a back seat here. Romero is far more interested in his subjects’ personalities. He gets them to talk about their daily lives, about their families, about girls. Reggie Jackson reflects on the good and bad sides of fame and on his treatment by the press. He muses about why money is important—he’s looking for freedom, he says, for control over his own life and for the ability to do the things he wants, and in America for a black man there’s only one way to achieve that. He does this while washing his car, shirtless.

It’s not that sports are unimportant or that Romero ignores them, but he’s clearly more interested in what an athlete thinks about the games than in the games themselves. Records and championships and on-field achievements become opportunities to muse about the nature of competition and athletic performance and about the abstractions that drive an athlete. All of Romero’s subjects become philosophers, of a sort: His camera finds them at their most thoughtful, even when their musings aren’t themselves especially unique or intriguing. And when they’re not particularly articulate, he at least gets them to be sincere. We get real insight into them as people. Harris is quiet and gentle, and if he doesn’t seem like a particularly complicated person, he is sweetly earnest and still coming to terms with the idea of being a public figure. Jackson seems less cocky or flashy than self-assured, confident not only in his abilities but in his own value and determined not to let himself be taken advantage of. Stargell comes off as astonishingly normal, a pleasant suburban dad who likes his job but isn’t singularly defined by it.

Sammartino carries himself with a wrestler’s sense of showmanship, but he’s also clearly driven by lingering insecurities and the need to prove that he’s worthy of his bluster—and by deep-seated trauma stemming from his childhood in wartime Italy. But when he talks about his childhood, it’s mostly a story about his mother’s heroism, keeping Bruno and his siblings alive during the Occupation.

If the fit between Romero and sports was awkward, it was productive. It’s the reason he felt comfortable reshaping something as formulaic as the biographical sports documentary into a series of character studies. There’s no sense of triumphalism, no climactic moment in which everyone celebrates a championship. They’re low-key, talky movies full of little observations about the athlete’s day-to-day experience: whom they spend their time with, what they do for fun, what being them is like.

By the time Romero returned to feature films, he’d taken that lesson to heart: Whatever kind of thing you get to make, whatever you can convince funders is worthwhile, doesn’t need to dictate what you do with it. His fit with horror was equally awkward. It’s not that he hated horror—he liked it fine, just as he liked the Steelers fine—but he had to consciously reshape the genre to accommodate the stuff he actually wanted to make movies about. This approach to horror was already implicit in Night—essentially a dialogue-driven stage play about people growing increasingly agitated, bracketed by zombies. But by 1978’s Dawn of the Dead, the first Romero film since Night that opened in wide release, it became an operative principle. If I have to be the Zombie Guy, I can make a movie with zombies that’s not exactly scary, and which is mostly a savage satire of consumer capitalism.

Romero never got the career he wanted for himself—not that many people do in the film industry. But there’s something almost heroic in the way that he figured out the genres he'd be able to work in and then proceeded to shape them—sports docs, zombie movies—into something that he could be passionate about. It’s what makes him such an interesting filmmaker, and what made him so hit-and-miss at the box office: Whatever people want out of their run-of-the-mill horror movie is not what they’re going to get out of Martin or Day of the Dead or Creepshow. He never made the same movie twice, even though a full third of his feature filmography has the word “dead” in the title. Romero took what he could get and did whatever the hell he wanted with it.