As Passover commences this Saturday evening, I’m thinking about my friend’s refrigerator, and Elvis Presley.

This train of thought is, well, different from all other trains of thought. See, my buddy just moved into a new house, and while familiarizing himself with its kitchen appliances he found portions of the owner’s manual for his new Frigidaire that he couldn’t keep to himself. He texted me photos of the documents devoted to “Sabbath Mode.” This is a programmable feature that disables various switchable functions on the refrigerator, such as the light triggered by opening and closing the door, and the icemaker. That makes it easier for members of the Orthodox Jewish community to play by their religion’s rules for the weekly Sabbath and high holidays (no driving, working, lighting a candle, or turning on anything electrical among them) and stay good with God. My buddy’s Jewish, and I’m Irish Catholic, though neither of us observe other than to occasionally please extended family. But this Sabbath Mode appliance thing was new to both of us.

Turns out it’s a big deal, and getting bigger. I called up Star-K, a Baltimore-based group that’s the leader in promoting the production of state-of-the-art appliances that factor in the ancient rules followed by observant Jews. The organization's core chore at its founding half a century ago was certifying food producers as authentically kosher. Avrom Pollak, Star-K’s president, told me the Whirlpool Corporation inspired his group to establish a “kosher appliances” certification process in the 1990s. The now-Michigan-based manufacturer and Star-K cooperatively designed the first oven range that could be programmed to fit old-school religious rules. Generally, this means deactivating digital thermometers and clocks for one day a week. Refrigerators and dishwashers that work a 24/6 schedule came next. Sabbath Mode was born.

“Only a small percentage of Jewish people observe the Sabbath, so only a tiny fraction of the overall population would specifically look for this technology,” says Pollak. “So you’d think companies wouldn’t [bother developing Sabbath-mode software]. But if you’re selling appliances, you don’t want to lose that market share. That’s the driving force. More and more companies are adding the Sabbath mode.”

Historically, members of the Orthodox community who got caught in a technological bind during a biblically mandated off-day were sometimes left searching for a non-Jew who could turn dials or flip switches without peeving their deity. Gentiles who performed these menial tasks to help out the devout were dubbed “Sabbath goys” or “Shabbos goys” or “Shabbos boys.”

By now, according to Pollak, his group has worked with “about 30” major appliance manufacturers the world over to develop features that should eventually make the Sabbath goy obsolete.

Well, I’ll be. I called my buddy to tell him that basically his refrigerator wasn’t an outlier, but was instead part of a trend. That got us to talking about the most famous Shabbos goy either of us knew: Elvis Presley. I was a massive Presley fan when I was little, ever since the dad next door played me his live LP from 1973, Aloha From Hawaii. I kept my love for the King mostly closeted at first, since he was a bloated man in a sequined jumpsuit for most of my childhood. But as I got older, I read lots about him and bought box sets, even from his Vegas era, and made a pilgrimage to Memphis three decades ago to experience the over-the-top Elvis Death Week celebration in person.

My obsession has waned some since that boffo trip. But my buddy’s refrigerator episode and my talk with Pollak reminded me of the oddest thing I learned about Elvis way back when: Before becoming the King, he’d served as a Shabbos goy for a neighboring family in Memphis. He was the first Shabbos goy I’d ever heard of. (Until then, I don't think I even knew there were Jews in the South in the 1950s.)

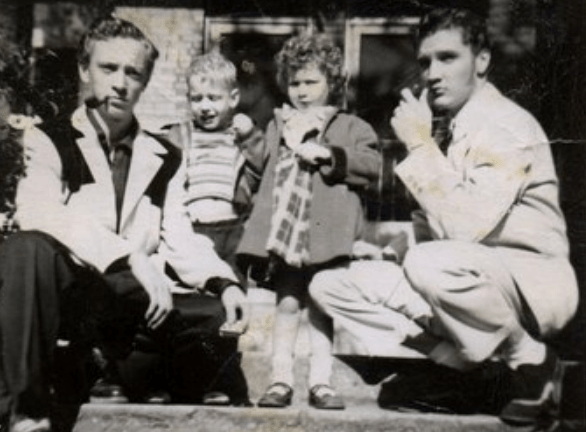

Presley grew up in a duplex at 462 Alabama Street in Memphis. Alfred Fruchter, an Orthodox rabbi, occupied the two-room flat upstairs with his wife and children. The young Elvis apparently couldn't help falling in love with Jews: Fruchter family legend holds that after the rabbi’s son, Harold Fruchter, was born in July 1952, Elvis came out to the street when they arrived home from the hospital and asked if he could have the honor of carrying the newborn upstairs. Jeannette Fruchter, wife of the rabbi and confidante of Elvis’s mother, Gladys Presley, handed her baby over to the future king of rock and roll.

And that when Elvis came home in 1954 with his first Sun Records release, "That's All Right, Mama," he didn’t have anything to play the record on. So Fruchter let Elvis use his phonograph.

Peter Guralnick’s 1994 biography, Last Train to Memphis, quotes Elvis talking about his relationship with the Fruchters and performing chores for the family during the Sabbath.

“He was really nice to me,” Presley said of Rabbi Fruchter in 1955, according to Guralnick’s book. “He’d loan me money, and sometimes he’d ask me to turn on the lights for him on Saturday.”

The Fruchters left Memphis in 1955 as Presley was on the verge of superstardom. Rabbi Fruchter died in 1994. Jeannette Fruchter died in 2003. The Fruchter children I spoke with confessed that their memories of life under the same roof as Elvis are limited to what their parents told them about those days. But they admit it’s pretty cool to know that a guy who would soon set the world on fire once lit the stove for their family if needed.

“My birth certificate has Elvis Presley’s address,” Harold Fruchter, now 68 and living in Philadelphia, tells me. “How many people can say that?”

“That’s such a throwback now, the notion of a Shabbos goy,” says Judy Fruchter Minkove, Harold’s sister, who was born in 1954 and resides in Baltimore. “I was so young. But it is interesting to think about!”

Yet over time, Minkove says, she’s occasionally reassessed her feelings about the role Presley played in her home. Because in the years since Presley’s 1977 death, a lot of momentum has been given to the notion that the most famous Shabbos goy of all time wasn’t a goy at all.

“It’s Elvis’s Birthday And, Yes, He Was a Jew,” reads a 2015 headline from Haaretz, a century-old Israeli newspaper.

Really?

“If you’re in an uninterrupted maternal line of Jews, you’re considered Jewish,” says Roselle Chartock, author of The Jewish World of Elvis Presley, the latest book to mull Presley’s Hebrew roots. “Elvis is.”

The main evidence for Presley's being Jewish is that his maternal great-great-grandmother, Nancy Burdine, was a Jew of Lithuanian descent. Until recent years, Presley’s bios pumped up only his Christian bona fides and ignored the matrilineal bloodlines. He was baptized as a kid by a Pentacostal preacher, and learned to play guitar at the East Tupelo First Assembly of God, the church in Tupelo, Miss., that his family attended before moving to Memphis. But Chartock says her research shows that Gladys Presley had informed her son of his Jewish ancestors, only to have a tyrannical manager, Colonel Tom Parker, warn him that any hint of Semitism could cripple his marketability.

Yet Presley did occasionally flaunt flourishes of Jewishness. There are photographs of him onstage in the early 1970s wearing Star of David and Chai (Hebrew for “life”) pendants around his neck, for example. Then there’s the headstone he made for his mother. Gladys Presley died at only 46 years old in August 1958, and was buried in Forest Hill Cemetery in Memphis. Elvis, a dedicated mama's boy, designed a marker that featured a Star of David, and placed it at her gravesite in December 1964.

But that headstone went missing under the bizarrest circumstances imaginable. Elvis, only 42 years old, died on August 16, 1977. He was originally entombed in a mausoleum at the same cemetery as his mother. But on August 29, three men were arrested at Forest Hill and charged with conspiring to snatch the King’s body, which was barely cold. Prosecutors initially alleged the perps confessed to intending to put dead Elvis up for ransom. But the plan as outlined by investigators never made any sense. Presley’s casket was surrounded by slabs of rock and weighed a reported 900 pounds, and the suspects had no heavy equipment or explosives when they were nabbed. Prosecutors dropped the case after admitting that all the evidence of a grave-robbing conspiracy had come from a suspect who had recanted.

But family patriarch Vernon Presley, saying he feared a copycat crime, brought the bodies of both Gladys and Elvis to Graceland for reburial in October 1977. There Vernon replaced the headstone from Forest Hill with a new marker that featured a Christian cross and a statue of angels, but no Star of David. The headstone with Jewish iconography disappeared from public view, and might have stayed there forever were it not for the efforts of Graceland’s staff archivist, Angie Marchese. According to 2018 reports, Marchese had found the missing marker in a warehouse full of literally more than a million Elvis artifacts. And without any publicity, it was placed in Graceland’s Meditation Garden that year. The link between Gladys Presley and the Star of David was again out in the open. "We decided we didn't want to make a lot of fanfare about it," Marchese told the Memphis Commercial Appeal about the Star of David–embossed headstone’s hush-hush return. "It was just done to honor Elvis's mom and to fulfill what we think would have been his wish."

Minkove, who with her brother was interviewed for Chartock’s book, says she finds the case for the King’s Jewishness compelling, and bittersweet. She’d be proud to welcome the guy who treated her family so swell to the tribe, on one hand. But on the other: “My parents never would have asked Elvis to turn lights on if they knew he was Jewish,” she says.

Harold Fruchter has stayed Kosher and very observant of Sabbath rules. He recently moved from the D.C. area to Philadelphia, where his daughter, Hadas “Dasi” Fruchter, started her own Orthodox synagogue and was recognized as the first woman in the city to do so. His new home in Philly didn’t come with a refrigerator with a Sabbath mode, however. But he doesn’t bring in a gentile to perform the tasks the King performed for his family all those years ago. “Before the Sabbath, I tape the automatic light switch on the refrigerator so it doesn’t go on and off when I open the door,” he says.

It also turns out Presley wasn’t the only musician at that Alabama Street address in the early 1950s.

For the last 40 years, Fruchter has been guitarist and lead singer for Kol Chayim Orchestra, a combo that does bar mitzvahs and weddings, etc. Musicologists have actually debated whether Elvis’s art was influenced by the cantorial tunes played by the rabbi upstairs, but there’s no clear consensus. It’s inarguable, however, that Harold Fruchter’s music was impacted by the good boy who lived beneath him.

“We do some Elvis songs,” he says.

Not between sundown Friday and sundown Saturday, however.