The Time To Talk About Fixing NFL Player Healthcare Is Now

1:12 PM EST on January 10, 2023

It really did look normal again on Sunday, at least to a casual football viewer. Another NFL game day rolled into our communities and our bars and onto our televisions. There were fans tailgating. There were commentators sitting at desks offering their thoughts on who would win and who would lose. There were packed stands and, soon enough, great plays to fill out the highlight reels. It's not that the near-tragedy of last week's Monday Night Football, when Bills safety Damar Hamlin collapsed on the field in cardiac arrest after a routine tackle, had been forgotten. It was still present in the signs and shirts honoring Hamlin in every game, in the remarks about his continued recovery during the broadcasts, in quarterback Josh Allen's comments, after Buffalo's win, that Hamlin's recovery reminded him that God is real. But with Hamlin's condition continuing to improve—he tweeted during his team's game on Sunday, and was progressing well enough that he transferred to a new hospital on Monday—the fears about the physical risks inherent to this country's most popular sport naturally receded into the background. The crisis had passed, and football, in all its smash-mouth glory, was back in the foreground.

This is how this sort of thing works—how humans rationalize risk, and how media cycles work, and how the NFL justifies its existence from one Sunday to the next. Football cannot love you back, and won't; this is something everyone that cares about it knows, and has to shove into the recesses of their mind. Your teammates can love you back. Your coaches can love you back, if you get good ones. But there is no way to deny the physical toll the sport takes on the human body. The bad knees. The aching backs. The brain disease. Football remains a billion-dollar global empire that offers its workers—in this case, the players that play the sport and risk their lives for our entertainment in so doing—the flimsiest of safety nets, both while they are playing and after they're done. There are many ways in which this manifests: the league's not-really-guaranteed contracts; the seasons necessary to vest into the NFL pension (it's at least three; Hamlin, in his second season, is not yet vested); the strict limits on the healthcare that the league provides former players; the shameful exclusion of black players from the CTE settlement.

The promises the NFL makes to its players are few and fleeting—it starts with a rookie deal and not much else. Hamlin, currently, is not vested. He has no pension promise. He has no guarantee of comprehensive health insurance after he retires. His financial future, past his rookie deal, which has another two not fully guaranteed seasons left on it, is now likely dependent upon the generosity of the billionaire Bills ownership, whose decision will almost surely align with whatever public sentiment is. Right now, that sentiment is clear and supportive. But also it is the nature of the business to forget.

It doesn't have to be this way. In about seven years, the NFL players will return to the bargaining table with the owners for a new collective bargaining agreement, which will outline issues like healthcare, pension, and player contracts. As always, whether the owners do what is right—extend more healthcare, more benefits, and more money for current and former players—will hinge on several factors, including if, after the shock and fear of Hamlin's cardiac arrest fade into memory, football fans and media alike can demand that owners give football players what they deserve.

A contract is a contract, except in the NFL. Rookie contracts are either mostly or somewhat guaranteed, depending on where a player is selected. Beyond that, the contracts of elite quarterbacks who are deemed key to the team's success will be fully or nearly fully guaranteed. But that's a relative handful of guys, and players who are not within that group at the very highest and lowest ends of the league's pay scale do not have fully guaranteed deals. Take, for example, this 2021 NFL memo, which made clear that even a training injury that occurred away from team facilities and outside team supervision could be deemed a "non-football injury"—a polite way of saying that the injury was not a team's problem, and could let a team out of paying a contract.

There are many legal arguments against guaranteed contracts in the NFL, and you have probably heard all of them. There's the salary cap (which does not create parity), the "fully funded" rule (an archaic piece of language from the NFL's early years that should have been done away with years ago), and even blaming the players themselves for not winning the right to guaranteed deals during collective bargaining (a complaint that requires ignoring the entire labor history of the NFL, including the history of NFL quarterbacks scabbing their own union and once nearly destroying it, as well as NFL fans openly attending scab games). As the football historian, former NFL lineman, and distinguished professor emeritus at Oregon State University Michael Oriard told me back in 2020 about guaranteed contracts, "This is a fundamental labor right that football players don’t have, and they could only gain it at enormous cost to themselves as well as to the owners. And it just ain’t gonna happen.”

Perhaps the most insidious argument against guaranteed contracts, though, is one that every football fan has heard, perhaps even from their fellow football fans, which is that the sheer amount of injuries makes it impossible to guarantee anyone's contract. But if football is violent, and if its brutal consequences can go from conceptual to all too real in the flash of a moment, to the point that a player could die on the field, and if owners refuse to guarantee contracts to preserve their competitive flexibility, it still doesn't justify or even explain why NFL players don't have lifetime healthcare.

As with contracts, it helps to start with how stingy NFL insurance currently is for former players. First, know that the league has two types of players: vested, and non-vested. A player is vested after three credited seasons, which is approximately the average length of an NFL career. Running backs, wide receivers, and cornerbacks are among those positions that have, on their own, shorter-than-average careers. A good chunk of NFL players never get vested.

A vested player has about three pages of benefits they can look forward to after leaving the game, according to the NFL's own paperwork. Most importantly, they are eligible for up to five more years of extended health insurance. They also have access to the "former player life improvement plan" an ornate description for some more benefits such as help with (almost surely necessary) joint replacement surgeries, as well as pension benefits starting at age 55.

On the one hand, I don't have a pension and no job has ever guaranteed me five years of health insurance after leaving. This is the type of thinking that owners love to see, and encourage. Most Americans don't have those kinds of guarantees, but also none of my previous jobs here in the United States have put me at risk of great bodily harm on a daily basis. There is no concussion crisis in U.S. journalism. There are not ambulances parked outside most U.S. office spaces, just in case. The billionaires who own sports teams are also unlikely to suddenly become paralyzed in their workplaces. In a more perfect world, or just a country that functioned better and less cruelly than this one, all of the aforementioned would have universal healthcare for the rest of their lives.

But this is not that country, and if anyone working in this one deserves to be among those at or near the front of the line in the U.S. for such a benefit, it is people who live with the consequences of weekly violence upon their bodies long after we have all stopped watching them on the field and forgotten their names. (Obviously, there are many other workers who also deserve to be at the front of the line. I simply ask for us to agree that this group includes football players.)

And those five years of healthcare that NFL players receive is something they get only if they are vested. It gets much worse for those who never make it to that point. A non-vested player, according to the NFL's own paperwork, gets, uh, severance pay. There are not five more years of healthcare. No help with anything like joint replacement surgery. They do get dental and vision insurance, and there's a disability plan, and a smattering of other niceties. But there's no health insurance, and there's no pension. Football is done with you when it's done with you, and every player has to live with the consequences when that time comes.

If the past is any indication, it's likely the Bills will handle Hamlin's contract the way the Pittsburgh Steelers handled the contract of Ryan Shazier. The linebacker was on the fourth year of his rookie deal and appeared to be a rising star when he suffered a spinal contusion on a tackle in 2017. Shazier's story is, in many ways, what any person would wish for Hamlin: He survived, got married, started his own charitable foundation, and can walk. He even danced at his wedding. That recovery was made while being paid by the Steelers for two years. The team converted Shazier's contract into mostly a signing bonus in 2018 and tolled his contract in 2019, giving him two more years of salary plus health benefits while he recovered, as well as two more seasons toward his NFL pension. Shazier never played a snap after that injury, but he retired in 2020 after six seasons, more than enough to be vested.

I read all the Shazier stories during his recovery, and read that Shazier over and over again thanked the Steelers organization for its generosity. But why was his recovery hinged on the benevolence of rich men, who were surely doling out that benevolence because of how bad it would look if they didn't? All the current system does is provide pats on the back to billionaires for daring to do the right thing. There is no real incentive, beyond some residual fear of public shame, to do any more than the least.

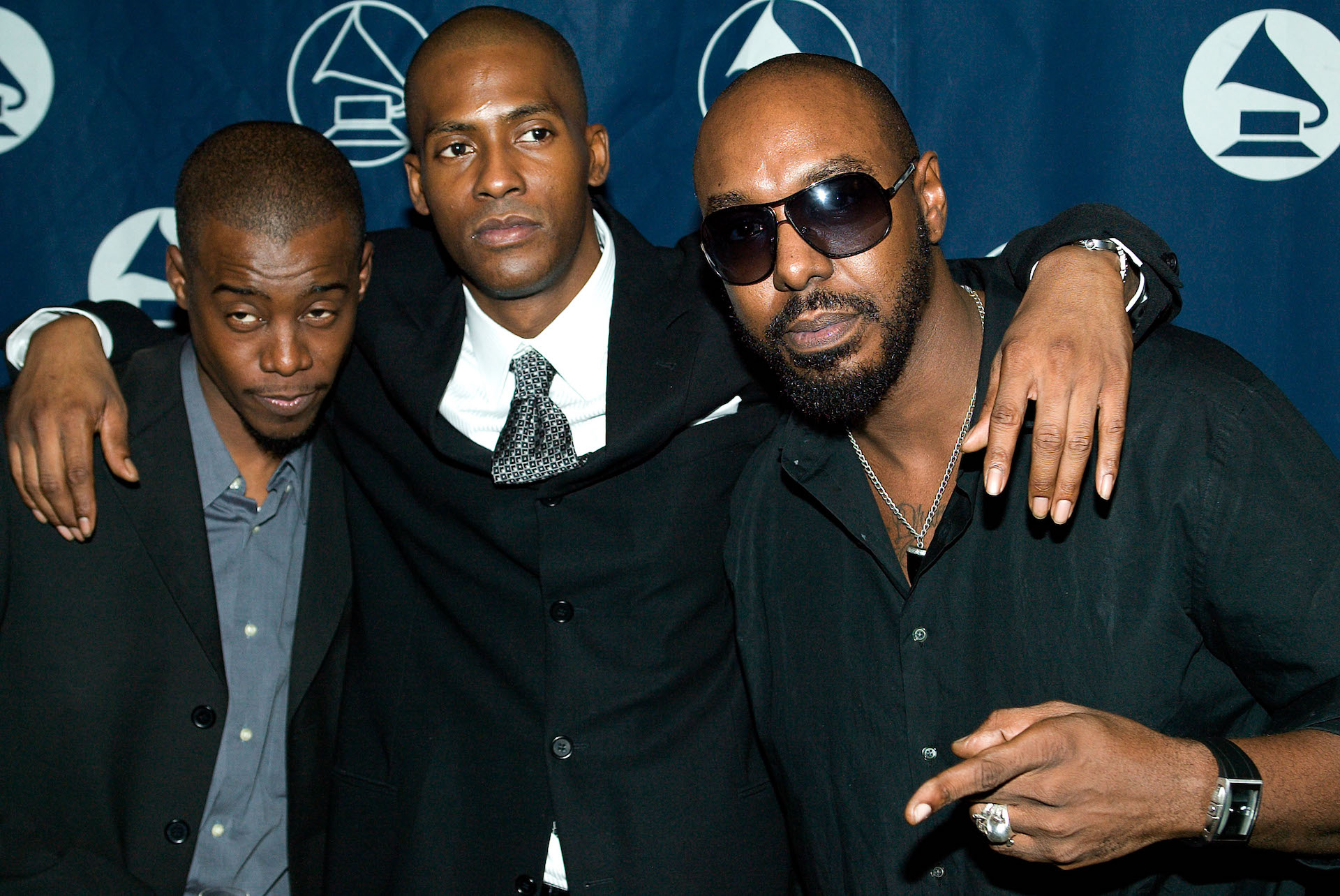

I am indebted, on this topic, to an excellent conversation between former player Domonique Foxworth and NFL analyst Mina Kines on her podcast. Foxworth, who also served on the NFLPA's executive committee and served as president, outlined exactly how little the NFL is required to give Hamlin, who nearly died on one of its playing fields.

"So the five years of healthcare that I enjoyed? He don't get that," Foxworth said. "The pension that I will enjoy when eventually I take it out? He don't get that. His family doesn't get that. Like, he is not. And that ... " Kimes finished Foxworth's sentence, here. "That's an outrage," she said.

There are even more ways in which the NFL gives the bare minimum to its former players, from the CTE settlement delays to cuts to disability benefits for former players, which the radio host and former college football player Garrett Bush read aloud on the Ultimate Cleveland Sports show.

Here's the scary side of the Damar Hamlin story nobody but @Gbush91 wants to talk about. pic.twitter.com/X4Wgx0dXs4

— Ultimate Cleveland Sports Show (@ultCLEsports) January 4, 2023

"You don't want to pay for somebody that's broken and battered and can't take care of themselves because it costs you money. So it is all about money!" Bush said. "We worship these owners. They do anything they want to. Anything! And so long as the product is good, we salute it!"

At this point, it's helpful to bring in the series finale of the HBO show Ballers. Yes, the show was not too grounded in reality. It burned through plot like a book of matches already on fire; almost every problem got solved in the very next scene; famous people just appeared all the time for no reason. Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson portrayed a former player turned money manager who, over the course of the series, became the owner of Kansas City's football team. There's also a fake Jerry Jones who kinda looks like Jerruh and talks like Jerruh and also owns the Dallas Cowboys but nobody actually calls him Jerry Jones. They call him "Bossman" instead. Strange show!

In the Ballers universe, the NFL owners are not asking for a 17-game season, as they recently got, but an 18-game season. The Rock—his character's name is Spencer Strasmore but he's as assuredly The Rock in this as he is in every part he plays—decides that, as a former player, he can only agree to this if the owners agree to lifetime healthcare for current and former NFL players. The Rock thinks he has this vote locked up, but then Bossman betrays him and delays the healthcare vote because it needs "more research" after getting The Rock to vote for the 18-game season. The Rock will not stand for this! He is The Rock! He takes a secret meeting with the players union, which turns out to not be so secret because the other owners find out and suspend him from ownership. The Rock's money guys also yell at him a bunch and the owners try to smear him in the press, but The Rock fights back with a splashy New York Times article as well as a coordinated Instagram campaign of current and former players. They post images of their gruesome injuries.

This all culminates in another owners meeting. All the owners arrive in private jets except The Rock who, as a man of the people, rolls up in a luxury vehicle instead. The Rock pleads with the owners, telling them, "For once in your life do the smart fucking thing if not the right thing." Then a vote is called, again, on lifetime healthcare for all players with three or more credited seasons, including veterans. Some owners start to raise their hands but they need one more. The Rock looks Bossman in the eyes and tells him this is a chance to save his soul and, just like that, Bossman changes his vote to yes. In fact, Bossman, aka fake Jerry Jones, says this will take the league to an even higher level!

Ballers lasted five seasons, nearly two more than the average NFL career; its writers room included former Steelers running back Rashard Mendenhall, who played in parts of six NFL seasons. Sometimes I wonder why they ended the show with such a truly impossible dream: (fake) Jerry Jones giving every former and current NFL player lifetime healthcare, simply because it's the right thing to do. Because I have seen the rest of the series, I know that it happened for the same strange reasons that everything else on the show did. But this is a fantasy that points to a larger truth: The healthcare, benefits, and salaries that NFL players deserve will only happen when NFL owners agree to it. Except, in reality, The Rock does not (yet) own a football team. More than that, I cannot imagine the current ownership class taking a stand for anything except the obvious, which is making more money. For the players to get the healthcare they deserve (and should have had for decades, at least) they will have to negotiate for it in their next CBA. It's here, again, that Foxworth's words in that podcast are worth heeding.

"Negotiations: The result happens in that room, but they take place over the course of a long time. It's about building and creating leverage. So it was difficult during that time, in part, because the public was not on our side, and we were in negotiations with multi-billionaires who are printing money—and they were saying, We're not making money. And then we would say, That is absurd. And our players would then hear, and it influenced them, they would hear from the outside world: You guys make enough money. You're greedy. Hurry up. Get back to work. And media members saying the same thing. And that impacts the leverage in the negotiations.

"Our players have five years of healthcare after you retire. You have five years of healthcare. After that, you're on your own. Figure it out somewhere else. That, to me, is outrageous! And that's all we can negotiate given the circumstances and the leverage."

Bossman, at the last minute, was right—NFL owners should give players lifetime healthcare because it is the right thing to do, and it might well help make the league better as well. But when was the last time that a billionaire did the right thing solely out of the goodness of their heart and not because of intense public pressure and scrutiny? Do these seem like people who prioritize the well-being of others in general, or their employees in particular?

I don't know what the media landscape will look like years from now. I cannot predict what other lofty demands the team owners will have. I can only hope that football fans and the media remember how precarious everything felt in the moment when we all genuinely, rightly feared that Damar Hamlin might die playing a game to entertain us, to make us happier. The widespread support of the football fan community and media can't fix everything, but it can be a start. It can be something that we give to players beyond hopes and prayers and one-time donations: Leverage.

If you liked this blog, please share it! Your referrals help Defector reach new readers, and those new readers always get a few free blogs before encountering our paywall.

Investigations Editor. You can reach her at diana@defector.com or, if you prefer protonmail, dfmoskovitz@protonmail.com. If security is a concern, download the Signal app and send her a text at 929-251-8187.

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter