The NBA’s Vaccine Decision-Making Doesn’t Need To Be So Complicated

2:46 PM EST on January 22, 2021

In a public service announcement the NBA began running earlier this week, a smiling and slightly wizened Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, his beard peeking out below his mask, rolls up the sleeve of a gray UCLA shirt and receives a dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in his left arm. “Because of the COVID-19 virus, we have had to learn new ways to be together,” he says in the voiceover. “We’ve had to find new ways to communicate. We have to find new ways to play. And we have to find new ways to keep each other safe. For myself and my family, I’m going to take the COVID-19 vaccine.”

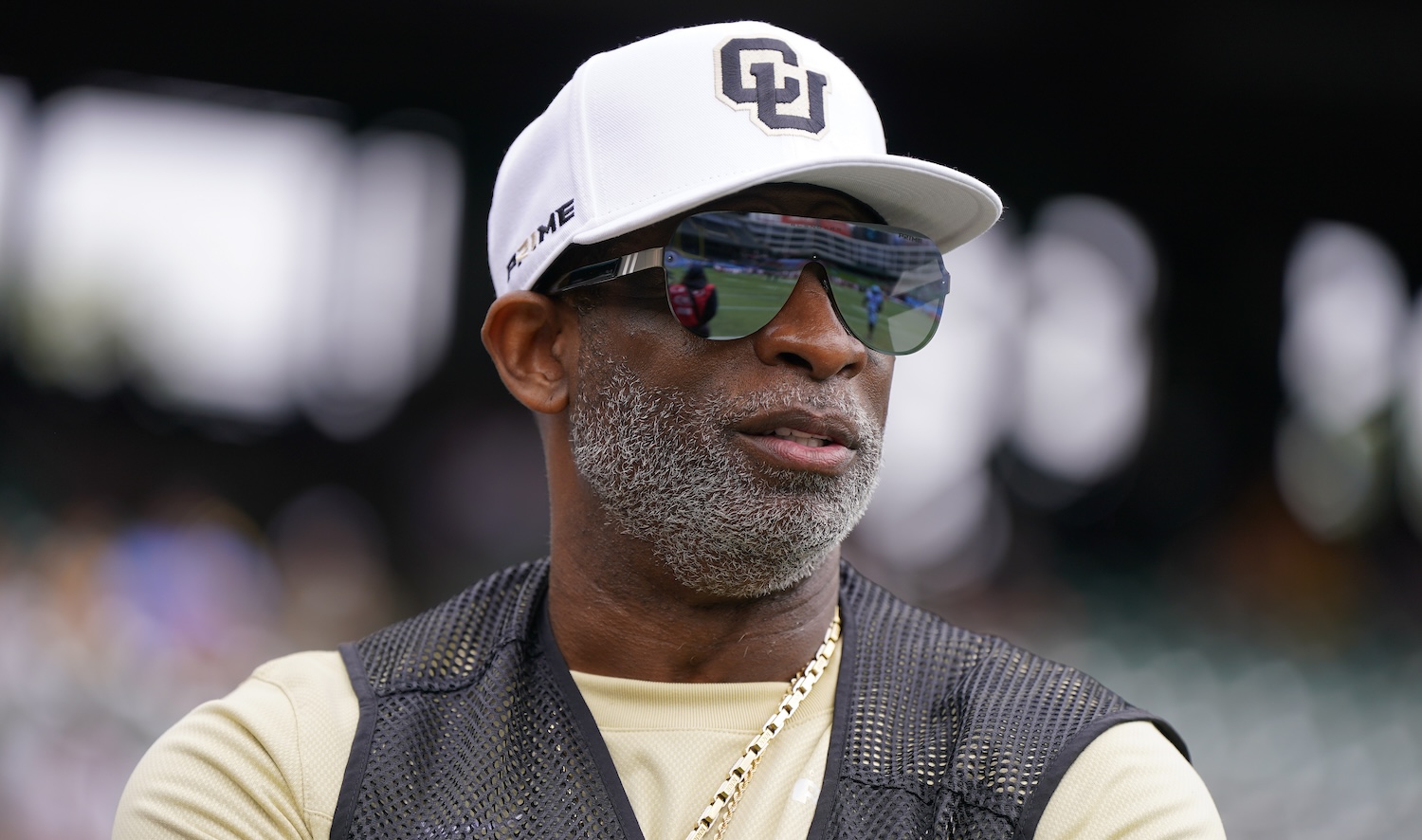

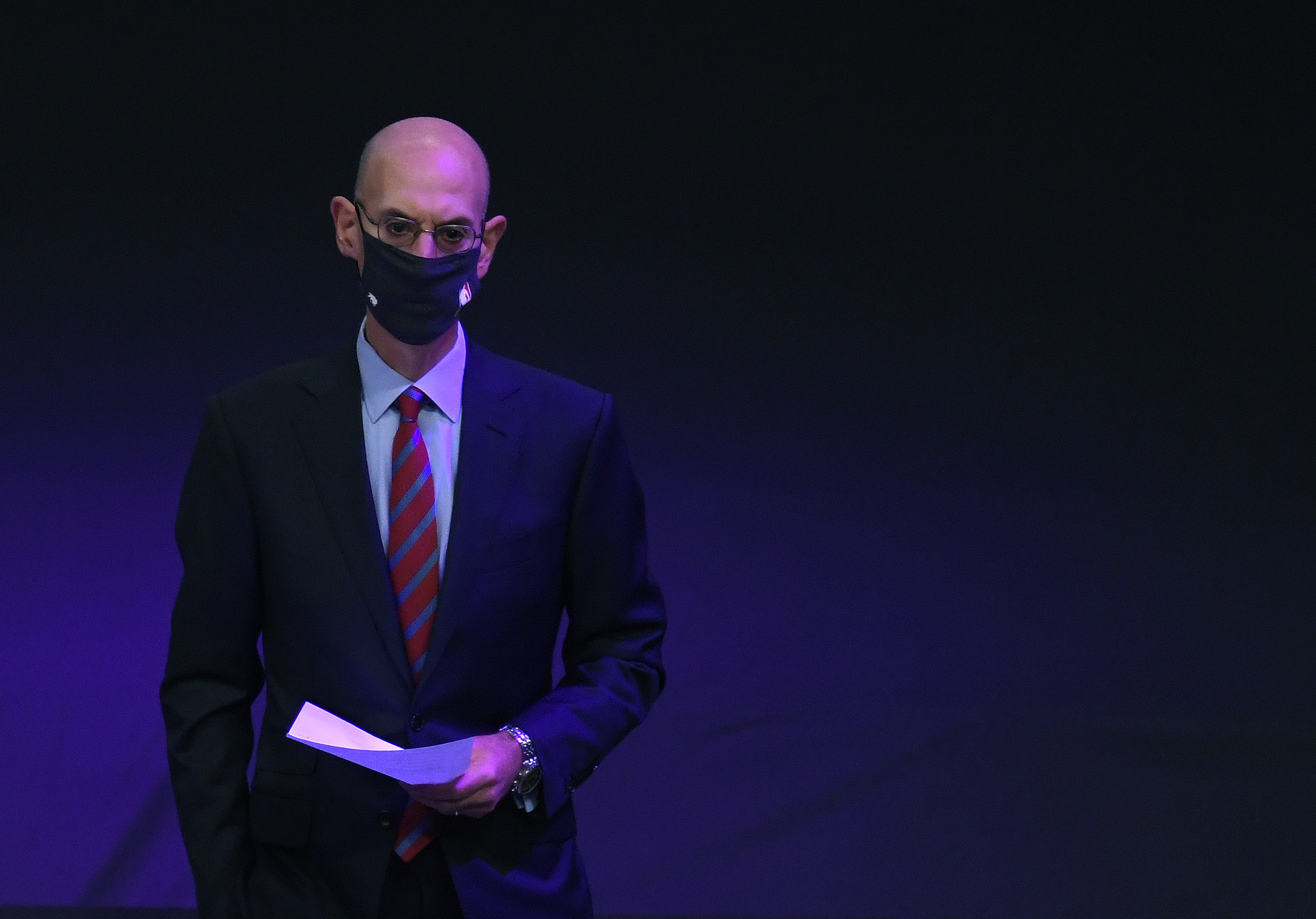

Twenty games have now been postponed since the NBA’s regular season tipped off a month ago, so it was only a matter of time before the league made known its interest in the overlap between “new ways to play” and “new ways to keep each other safe.” At the start of the season, Adam Silver told reporters the NBA would "in no form or way ... jump the line" for vaccines, and the league office circulated a memo forbidding teams from pursuing vaccine supply on their own. But in the last week, as vaccination access is expanded and ramped up, the league has shown some new openness to the idea of vaccinating NBA players early, as a kind of public service. (Not, as Charles Barkley suggested, because they deserve the vaccine more for paying higher taxes.)

... Is Charles Barkley drunk? pic.twitter.com/RC2cKik5q6

— philip lewis (@Phil_Lewis_) January 15, 2021

The Athletic’s Sam Amick mentions one idea floated on a call of team presidents last week: Players could volunteer at vaccine distribution centers across the country, receive the vaccine in that capacity, and act as vaccine ambassadors in the process. In an interview with Sportico on Tuesday, Silver himself confirmed that he'd been having some discussions to that end. “In the African American community, number one, there's been an enormously disparate impact from COVID," he said. "But now, somewhat perversely, there's been enormous resistance [to getting vaccinated] in the African American community for understandable historical reasons.” He cited conversations with public health officials who have said there would be "a real public health benefit to getting high-profile African Americans vaccinated to demonstrate to the larger community that it is safe and effective."

“Understandable historical reasons” is the cursory nod to centuries of exploitation and abuse in medicine, though the allusion doesn’t fully capture that the contemporary is context, too. Black Americans today are recipients of less-frequent and lower-quality care, and they report interactions with the health care system that range between demeaning and deadly. What Silver calls a perverse irony—that they might, as a result of the medical establishment's neglect, experience the worst of COVID-19, and also distrust that establishment as it administers a vaccine for COVID-19—is hardly a coincidence.

Nor are those circumstances so easily corrected by PSAs and theater. Michele Roberts, the executive director of the NBA players' union, said as much in a pretty frank interview with Yahoo Sports last week, when she was asked about a possible NBA player vaccination campaign:

Roberts pointed to the rollout of the vaccine, with a Black nurse taking it in New York on national TV and the reaction to it from a white former senator."She said, ‘I think we’re going to be fine. I mean, the first person to get the vaccine in New York was a Black nurse. And, you know, the Black community will see that and understand,’” Roberts quipped. “And I said, ‘You know, girlfriend, are you serious? Honestly, you resolve that problem with that image?’”

Roberts is right to point out the potential hollowness of a promotion like this. For obvious reasons, Silver may be overselling the power of stunts to remedy the results of injustice. She is also right to suggest that not everyone with “influence” will use it in ways Anthony Fauci would condone. (In a world that takes athletes’ word as scientific truth, we're all pondering the flatness of Earth between gulps of TB12 electrolyte concentrate.)

But Roberts goes a step further in this interview, a step too far. She raises doubts about the safety of the vaccine in a strangely coy and unproductive way. “But I haven’t made up my mind," she says of her own looming decision of whether or not she personally will take the vaccine. "I’m eager to be convinced that these are safe. I’m hopeful I’ll be convinced that they’re safe. But I’m not a cheerleader … I’m not at a place yet where I would wholeheartedly and fulsomely say, absolutely, you have to take it.”

Roberts may have taken the pulse of her membership, sensed high vaccine hesitancy, and decided she should be the one to preemptively take the fall. But publicly legitimizing safety questions about the vaccine—many of them already asked and answered in clinical trials and FDA hearings—amid a massive public health crisis is an awfully alarming way of honoring her obligation to the players, who are probably better served being familiarized with the science and made comfortable with vaccination.

If it's unfortunate, some clumsiness in navigating this terrain is maybe to be expected. A not-small segment of America has seen the pandemic through the prism of the sports world. (For much of February and early March, the virus was, to me, the thing that might screw up the NCAA tournament.) To Silver and Roberts, having that kind of captive audience may be flattering evidence of the institutional power of sports in America. But the outsize role of leagues in this crisis has always belied something a little sinister, too: the profound leadership vacuum of the Trump administration, which a mess of corporations and local authorities were awkwardly left to fill, however ill-equipped they were for the task.

On that front, there’s good news: A new administration took power on Wednesday, one that can actually be relied on for prioritization guidance and a clear, coherent public message on the importance of vaccination. New federal leadership won't solve all or even most problems. What it can do, though, is thoughtfully address whatever legitimate concerns people may have about the COVID-19 vaccine, relieve inexpert corporate leagues of their duties as government understudies, and tell them what role they ought to play now instead.

If you liked this blog, please share it! Your referrals help Defector reach new readers, and those new readers always get a few free blogs before encountering our paywall.

Staff Writer

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter