Sinner-Alcaraz Was Five Sets Of The Future

10:25 AM EDT on September 8, 2022

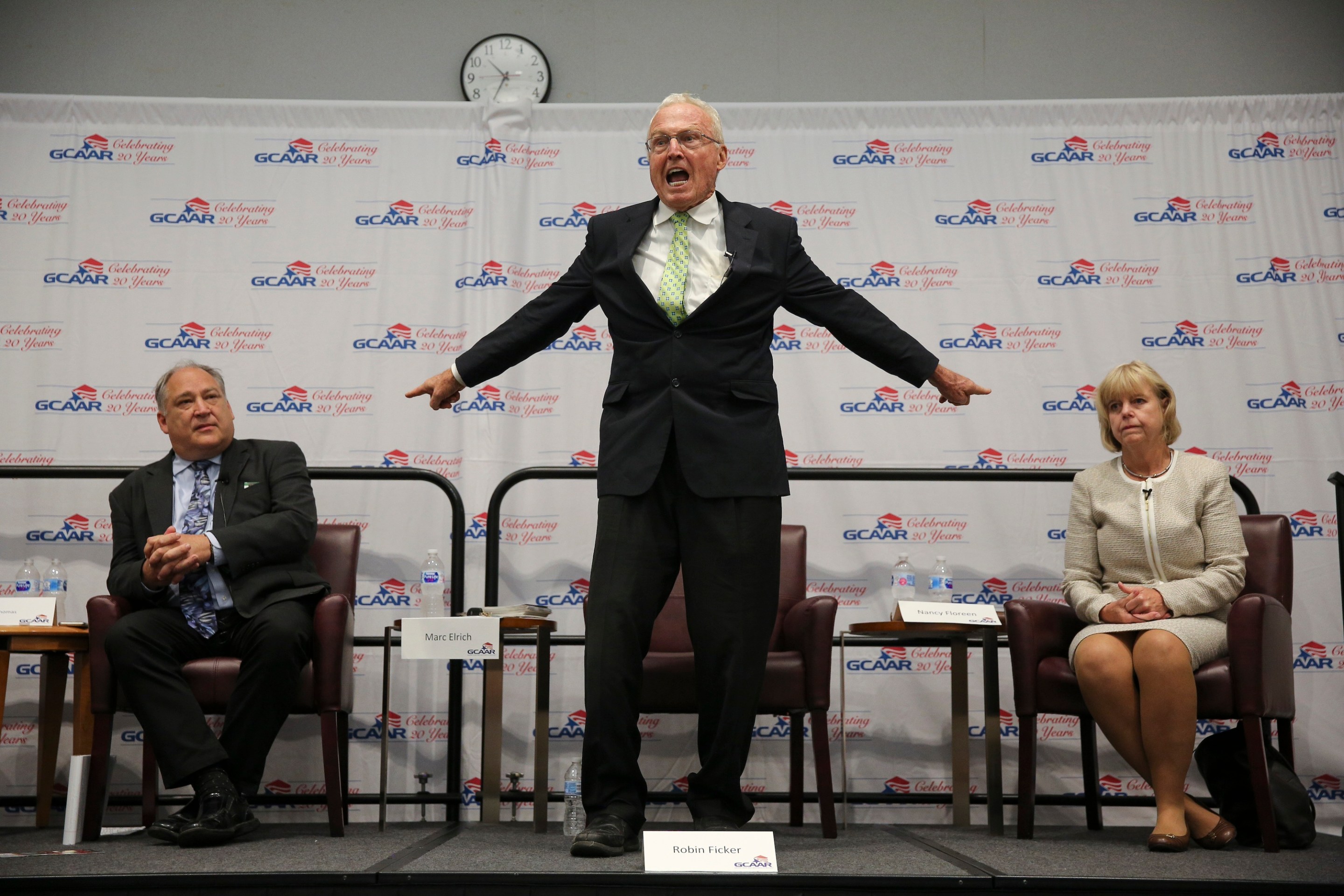

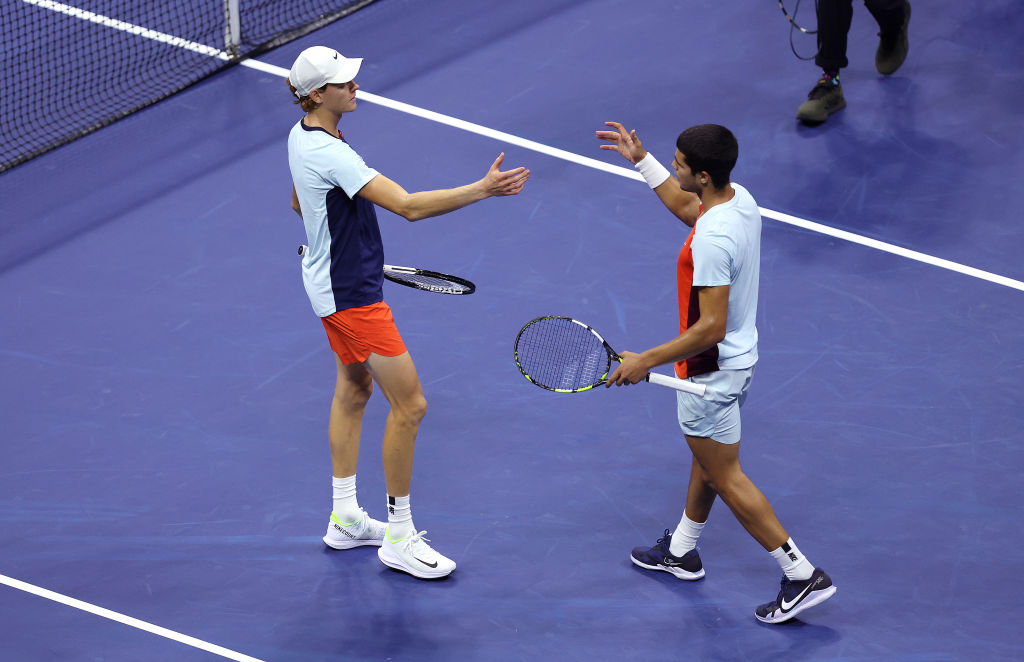

Reality got lazy with its metaphors: My pen ran out of ink. I only got it last month. But it was tasked with documenting every highlight, tactic, scoreline, atmospheric detail, and cathartic expletive for five hours and 15 minutes, and even then it only caught a fraction. The pen surrendered its innards in the effort and sputtered into retirement. I can't blame it. I'm tempted to do the same—close my eyes, cross my arms like a mummy, and rest forever—after witnessing what 19-year-old Carlos Alcaraz and 21-year-old Jannik Sinner just accomplished in that same timespan. I no longer fear the future, just my obsolescence in it. Tennis is hurtling into unknown territory and it deserves pens and scribes that can keep up. Alcaraz's 6-3, 6-7(7), 6-7(0), 7-5, 6-3 defeat of Sinner in their U.S. Open quarterfinal, which wrapped at 2:50 a.m. ET, wasn't just the match of the past decade. It was a smothering counterexample to any old head fussing about what tennis could even be after the old gods fade away. New gods take their place.

Besides sleep, what could you do for five hours and 15 minutes straight? How about the opposite of sleep: intermittent sprinting in every direction, batting a projectile at 125 mph, tracking a projectile moving at 125 mph, constant risk-reward calculations, ascetic emotional regulation, energy and pain management. And all this is done in solitude. All these players got from their coaches was increasingly hoarse yelling and distant physical presence; when Alcaraz looked in desperation to coach Juan Carlos Ferrero after flubbing a pivotal point, he received a chilly half-smile. At an age when lots of people can't be trusted with basic self-preservation, these two stood there and produced the highest caliber of tennis that any two men in the world could muster right now. Youth vitality melded with veteran technique, twice over. Nadal and Djokovic collaborate to create a distinctive style I like to call "wide tennis," but even that feels calculated and restrained in comparison to Sinner and Alcaraz, who seemed to be optimizing for audacity, unencumbered by better judgment or past experience. Rallies this explosive, inventive, and tireless can't be found anywhere else right now. Neither can a sequence quite like this:

Sinner and Alcaraz are friends, and for years and years ahead, frighteningly well-matched rivals. They've already met four times, with Alcaraz winning the first one last fall on indoor hard court. As Alcaraz flagellated the whole tour this spring, he appeared to be charting a path no peer could follow, and I prematurely worried if he'd ever be challenged enough to reveal his sickening potential on court. But then Sinner claimed both their encounters earlier this summer, the Wimbledon fourth-round on grass, and a Croatia Open three-setter on clay, recalibrating the expectations. They entered the Open as the No. 3 and No. 11 seeds. Their gifts heavily overlap: They have the best ground games of anyone in their cohort, all precision and spin and outer-range execution. But there are some differences. Alcaraz is superior in his foot speed and leaping, and skews a bit spicier in his shot selection, thanks in part to softer hands. Sinner has longer reach, once-in-a-generation timing that creates outlandish power with minimal expenditure, and (I must repeat) a Parmesan cheese sponsorship.

They also share a conspicious flaw. The staple skill at the top of the men's game is a powerful and consistent serve that earns low-effort points. For both Alcaraz and Sinner, the serve is a deficiency to be worked out in the future; at present, it's a boon to viewers, because tons of the points land in neutral position where both players must hit their way into a creative solution. Their lack is our gain. Together they managed 18 breaks of serve in 54 games, which is weird for a match of historic quality. Sinner, who attempted to serve out the match at 5-4 in the fourth set, came up with a few timely unreturned bombs but will also rue his 55 percent first-serve percentage and 11 double faults. It's possible that Sinner has a higher ceiling as a server—he's taller and has served a higher percentage of aces over the season—but that has yet to be realized. Alcaraz dug into Sinner's service games more than vice versa, winning 45 percent of return points to Sinner's 38 percent. In their previous seven sets this summer, Alcaraz hadn't managed to break him at all.

To lay out every intricacy of this odyssey would require a steady rewatch (or three) and the space of a short book. Every surface of it was embedded with tiny experiments, regrets and triumphs. Alcaraz toyed around with an unconventional wide position on serve; Sinner tried slinging those returns down the line. Sinner skunked his foe in the third-set tiebreak; he also blew match point on his serve. Alcaraz squandered a putaway forehand with set point in the second set; he also rampaged back down a break in the fifth. For both players, there were discrete moments where victory seemed almost inevitable. But Alcaraz is the one who advances to the semifinal, the first teenager to reach that stage of a major since Nadal won the 2005 French Open. His opponent in that semifinal, Frances Tiafoe, joked earlier in the day that he wanted a "super-long match, marathon match, and they get really tired come Friday." He got everything he wished for—as did any sicko who stuck around for the whole fight, and saw the game reborn.

this match is insane. I leave at 6am for the airport but I refuse to sleep and miss this. #Sinner #Alcaraz

— Coco Gauff (@CocoGauff) September 8, 2022

If you liked this blog, please share it! Your referrals help Defector reach new readers, and those new readers always get a few free blogs before encountering our paywall.

Staff Writer

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter