Nowhere Is Safe From Our Garbage

10:05 AM EDT on September 16, 2022

A golden dart frog perched near a phytotelma in a bromeliad.

The tiniest bodies of water on the planet are smaller than small ponds, big puddles, and even small puddles. They are not gouged into the earth but cradled by leaves, flowers, and other vegetation. This kind of waterbody is called a phytotelma—which is Greek for plant and pond—and they form serendipitously, when rain falls into the natural cavities of a plant and becomes a standing body of water where things can live, breed, and die. Phytotelmata—the very fancy and technically correct plural form—generally form in scoop-shaped leaves, like those in pitcher plants, natural water tanks, like bromeliads, fallen fruit, seeds like coconut shells, holes in trees, and the chambers inside bamboo.

Some phytotelmata are so astonishing that they appear conjured out of a Miyazaki movie. Many bromeliads have a spiraling rosette of leaves that trap water at the center, transforming them into a reservoir of water for other organisms. Here in this tiny pool, small organisms forage for food, take refuge from predators, and rear their young. Some frogs spend their entire life cycle within a bromeliad; it is their whole world.

Other phytotelmata are less wondrous, at least to our human eyes. Phytotelmata that form in rotting logs or among vine-like ficus roots can become unofficial nurseries for hordes of mosquito larvae and rat-tailed maggots—which boast a tube-like tail that allows them to breathe in stagnant, seemingly inhospitable, and definitely stinky water.

Oceans are forever, lakes last a long time, and ponds stick around for at least a few months each year. But a phytotelma's discrete size makes its existence unpredictably ephemeral. Individual leaves and flowers weaken and die. Any pool of water filled by rain can be dried out by the sun. Phytotelmata are subject to the vicissitudes of the elements: rapid shifts in water volume, temperature, chemistry, pH, turbidity, and even the communities of organisms inhabiting them, according to a 2014 paper in the Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society.

A group of scientists—Katarína Fogašová, Peter Manko, and Jozef Obona of the University of Prešov, Slovakia—recently set out to sample phytotelmata in teasel, prickly plants festooned with spiky flowers that resemble sea urchins, in eastern Slovakia. (At a glance, it might seem like phytotelmata are unique to rainforests and other tropical ecosystems. But temperate zones have phytotelmata too. The term was first coined in 1928 by Ludwig Varga in reference to the pools of water formed in the crevices of teasel leaves.)

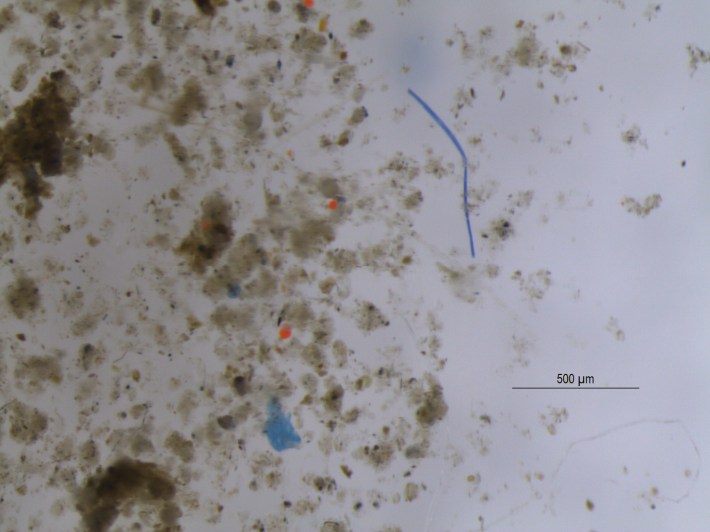

They wanted to understand what tiny communities dwelled in these tiny pools, which are common but last just a few months. But the scientists' sampling produced an unexpected result: itty-bitty blue, black, red, and white fibers and teensy orange and blue fragments were found in six of the 171 samples. In other words, several of these tiny, brief reservoirs were contaminated with microplastics. The scientists believe these are the first observations of microplastics in phytotelmata.

"These phytotelmata are very small and have a short lifespan," the scientists wrote in a report of their findings, published in the journal BioRisk. "The question is, therefore, how were they polluted with MPs?"

One theory the authors suggest is that the microplastics might have fallen out of the sky, deposited from the unknown number of microplastics that drift, suspended, in ambient air. Scientists still know very little about suspended atmospheric microplastics—where they originate and occur, where they go, and what the effects might be on our health and the world.

The authors' other potential theory came from their observation of living or drowned snails, as well as snail poop, inside the phytotelmata. Snails might have collected the plastics on or inside their bodies on land, and then slimed their way up the teasel to (unintentionally) deposit the plastics inside the phytotelmata. The authors include a zoomed-in photo of horseshoe-shaped snail poop containing a long blue microplastic, like a lone party streamer. (Poop warning: shows poop.)

So what is the takeaway from all of this? It's not news that microplastics are everywhere, blanketing the deep seafloor and surging through our own blood. Anywhere you look, there will probably be microplastics; it seems no environment, however tiny or remote, can be entirely protected from our horrible human trash.

Scientists are still learning about phytotelmata and the creatures that depend on them, such as this species of fighting fish that courts mates, builds bubble nests, and hatches fry inside nipa palm phytotelmata in Thailand, or this recently discovered mite that does whatever mites do in bromeliads in Brazil. The authors write that phytotelmata could be useful bioindicators of how much microplastic pollution exists in different habitats, which is one way to put a positive spin on it. Part of the beauty of these water bodies is in how their smallness encompasses an entire habitat, a tiny beautiful (and/or stinky) world. But all this wonder cannot protect them from our trash. The trash just got smaller, and found them too.

If you liked this blog, please share it! Your referrals help Defector reach new readers, and those new readers always get a few free blogs before encountering our paywall.

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter