MLB Owners Are Still Trying To Win The Labor Battles Of The 1990’s

12:04 PM EST on March 1, 2022

Defector has partnered with Baseball Prospectus to bring you a taste of their work. They write good shit that we think you’ll like. If you do like it, we encourage you to check out their site and subscribe.

This story was originally published at Baseball Prospectus on February 28.

Do you recall how the 1994-1995 strike actually ended? It wasn’t because of a proposal from the Players Association that finally satisfied the owners, and it certainly wasn’t because the league decided they were finally going to listen to what the union was saying. The strike ended because a federal judge ended it. The issues that led to the strike, and, to some degree, to the involvement of federal judge (and now Supreme Court Justice) Sonia Sotomayor, still remained at that point: it would actually take until March of 1997 for the PA and the owners to ratify a brand new CBA. They played with the 1990-1993 agreement in place from 1994 through 1996, because labor tensions that had built up and up for years finally came to a head in a way that made communication next to impossible.

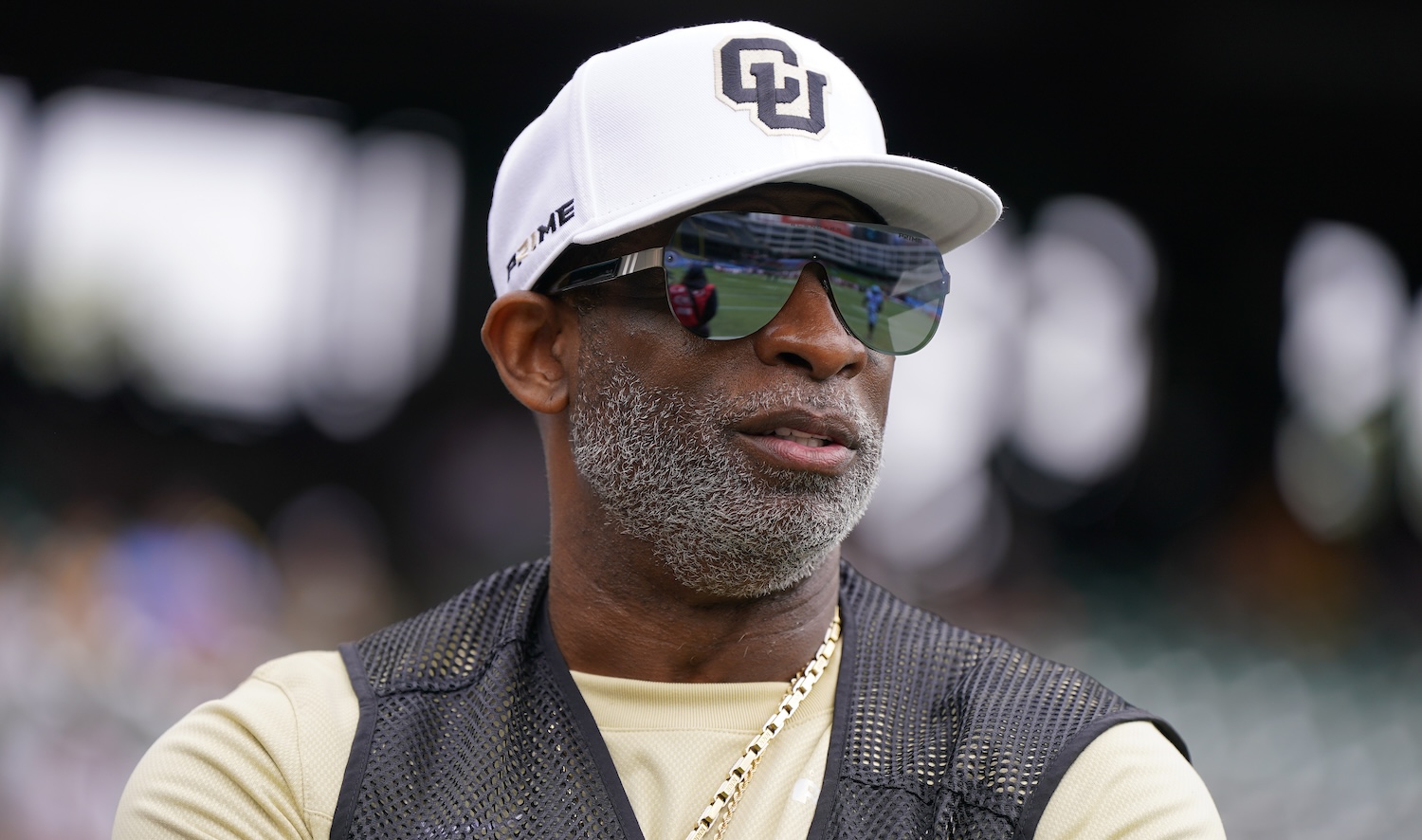

This is, as you were likely able to piece together on your own without this transition, a relevant bit of MLB history to consider in these times. The league locked the players out on December 2, at the exact moment the CBA expired, with commissioner Rob Manfred stating that, “we are taking this step now because it accelerates the urgency for an agreement with as much runway as possible to avoid doing damage to the 2022 season. Delaying this process further would only put Spring Training, Opening Day, and the rest of the season further at risk…” Fast-forward back to the present, and, well, this is being written less than 24 hours before Opening Day and some amount of the 2022 season to be determined is wiped off of the schedule. MLB was already clear about the fact that “a deadline is a deadline,” and that any games missed because of their self-imposed February 28 deadline for a new collective bargaining agreement would not be made up, nor would the players be paid for those canceled contests. A curious choice of words, that deadline quote, considering MLB’s flagrant disregard for the expiration date of the previous CBA, as well as the over 40 days it took for them to schedule a bargaining session post-lockout, but calling a hypocrite out for being hypocritical never gets you anywhere. So let’s move on.

We’re actually not done with the trip back to 1994, in part because of Manfred’s own words. In both his letter to fans regarding the lockout and in a press conference to elaborate further on why the league made this decision, he referenced the strike from that year. In the letter, it was to say, “we cannot allow an expired agreement to again cause an in-season strike and a missed World Series, like we experienced in 1994.” In his presser, Manfred stated that, “We made the mistake of playing without a collective bargaining agreement in 1994, and it cost our fans and our clubs dearly. We will not make that same mistake again.”

The mistake was strategic, and a calculated one. The league had locked the players out in 1990 in an attempt to push major economic changes into the CBA that would limit spending and player salaries while fundamentally changing the ways players would be compensated, and when the players balked at what looked a whole lot like a capped system with formulaic pay scales—one that would make it very difficult for free agents to be paid handsomely for their services—the owners reacted by locking them out. Remember, too, that the players still had plenty of justifiable anger and distrust over three years of collusion in the mid-80s; the fact the owners genuinely seemed to not understand why the players would even still be upset about that only inspired additional anger.

A four-year agreement was reached in 1990, the games not canceled by the lockout but bumped back so that a full 162 would be played. The two sides once again could not reach a deal before this one expired, and so the 1994 season began without a new CBA in place—the status quo of the previous agreement remained, however. Negotiations were tense, as anyone who lived through it or has at least read Jon Pessah’s The Game will recall. The league once again proposed eliminating salary arbitration and enacting a salary cap, but in exchange they would allow players to be free agents after just four years. Sort of, anyway. It would have actually been a restricted free agency, with teams having a right of first refusal for years five and six of a player’s career, and the PA would have also had to agree to put half of their licensing money into a revenue-sharing pool, too. You know, the licensing money the players used to help keep their strike fund full. As big of a fan of them as they are, MLB’s owners in 2022 didn’t invent “well, what’s the catch?” proposals.

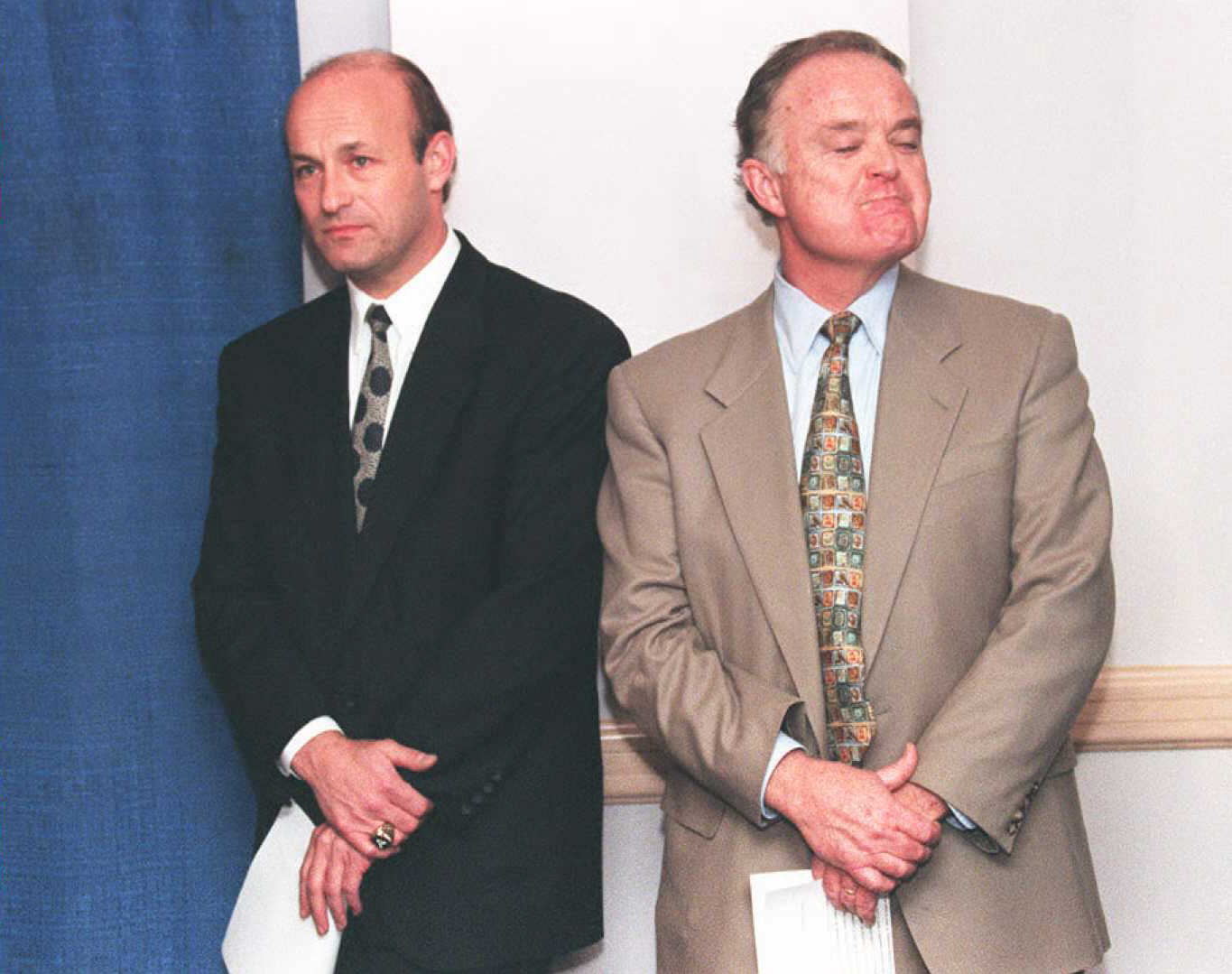

In August, after months and months of this sort of thing, the players went on strike: the owners were still pushing hard for that cap, and no agreement was going to be reached while that remained on the table. The players went into that strike assuming that fear of losing out on stretch run attention, as well as postseason revenues, would get the owners to drop their salary cap demand. They guessed wrong, and it’s because Bud Selig was in charge this time around. Selig was the acting commissioner, following the resignation of Fay Vincent, who had helped put an end to the 1990 lockout and eventually paid for that with his job. And Selig wanted a strike, because the league had a plan.

That plan was to break the union, and they would do it by any means necessary. As the players had gone on strike at a time when union support was diminishing and both fans and media had fatigue from all of the stops and starts and lockouts and past strikes, Selig felt that fingers would be pointed at the players for the canceled World Series. And even if there weren’t as many fingers as hoped, he planned to barrel ahead with a series of unilateral changes he felt justified in implementing as the commissioner. A little over a week after negotiations aided by a federal mediator failed to end the strike, the league’s owners added a salary cap to the CBA without the players’ input. The union responded less than two weeks later by declaring every union member a free agent. Eight days later, the owners’ executive council authorized the use of replacement players.

A little less than a month later, the salary cap change was revoked by the owners, but they also removed salary arbitration, negotiating between teams and players in general, and the anti-collusion protections. It’s not like the league was using the last of those very much, anyway. The union threatened that they wouldn’t lift the strike if a game was played with replacements, but it never got to that point, even if it got damn close. The National Labor Relations Board stepped in, getting the federal courts involved after MLB’s owners made unilateral changes to the CBA: that was bad faith bargaining, since there wasn’t actually any bargaining involved. This is where Judge Sotomayor came in: there was no other call beside the one she made, because there was no justification for what Selig and the owners had done, and therefore zero chance of them coming out the winners there. If you’re wondering how Manfred ended up getting a more significant role with the league later in the 90s, part of it is likely due to the fact that they needed someone around to go, “have you ever heard of ‘labor law’ before?”

The “mistake” of 1994 wasn’t beginning the season without a CBA in place, or a failure to lock the players out. It was the assumption that the owners could just bully their way to the CBA they wanted, and that they could either break the union or outright replace them if that failed. While Manfred and the owners of the present aren’t going to make that exact same mistake, you can certainly see similarities between the plans of 1994 and now. Like the lockout and collusion as lead-ins to ‘94, these players have the very public and very bad faith negotiations of the pandemic-shortened 2020 season on their minds, and the exploitation of every loophole found in the 2016 agreement as well. The owners forced a direct conflict by negotiating just enough to avoid setting off the legal version of “bad faith” bargaining, then locked the players out when, to the surprise of no one paying attention, time ran out on the previous CBA. They then waited 43 days to schedule their next bargaining session, and have mostly used the illusion of movement as their ally while waiting for the union to give up on their demands and/or capitulate entirely. If you think those $5 million bumps to the pre-arbitration bonus pool are meaningful progress in negotiations, consider that $5 million divided by 30 teams is $167,000 each. You can’t even get a top-end pilot for your private plane for that amount. The owners are still just wasting time, and waiting for the union to crack… just like Selig and Co. in 1994. Considering the players seem as unified and (justifiably) angry as they’ve been in ages, you should probably settle in for a very long spring, while recognizing, too, that there might not be a magic bullet proposal out there that’ll end this thing.

Manfred, by the way, was outside counsel for the league at that period in time. When he said he’s still the same guy he was back in the 90s, well, that might just be the most honest thing you’ll ever hear him say.

If you liked this blog, please share it! Your referrals help Defector reach new readers, and those new readers always get a few free blogs before encountering our paywall.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter