Baseball’s Erasure Of Black Managers And Executives Shows Who MLB Believes Is Worthy To Lead

2:23 PM EDT on March 22, 2021

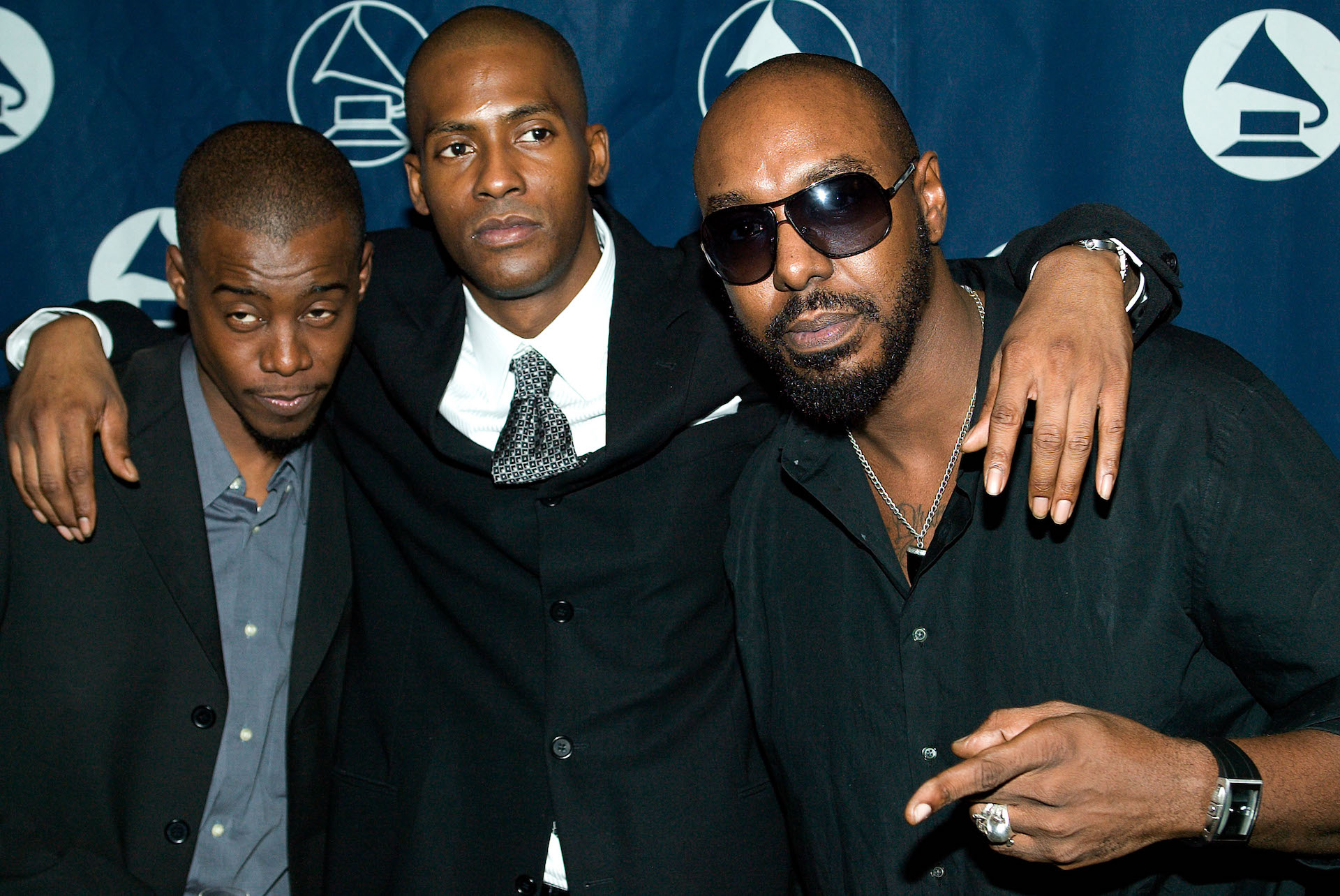

Connie Brooks, second from the right, the niece of 2006 inductee Effa Manley, accepts Manley’s Hall of Fame plaque from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum president Dale Petroskey (L), chairwoman Jane Forbes Clark, and MLB commissioner Bud Selig.

In 2006, 17 people affiliated with the era of segregated baseball were inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Their inclusion was greenlit by a special committee convened by the Hall to determine whether there were any from Black baseball (including the Negro Leagues and the previous, unorganized, period) who were deserving of baseball’s highest honor, but not yet recipients.

That the special election even occurred was momentous in itself. After all, it took Ted Williams advocating for Negro Leagues players during his own 1966 induction speech for the Hall to consider such a thing. “I hope that someday the names of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson in some way could be added as a symbol of the great Negro players that are not here only because they were not given the chance,” he said.

Before Williams delivered his speech and even for a few years after, the careers of the men and women who worked in Black baseball before Jackie Robinson’s historic turn with the Dodgers—most of whom were Black themselves—had been discounted and disregarded.

But Paige, the ageless right-handed hurler with a historic arsenal of pitches, did make it into the Hall in 1971. In 1972, Gibson, who was perhaps Paige’s only equal in terms of cross-racial popularity, was inducted alongside defensive first baseman Buck Leonard, the Lou Gehrig to Gibson’s Babe Ruth. Cool Papa Bell was given his flowers in ’74, and Oscar Charleston, the man many baseball historians consider the best all-around player the game has ever seen, was inducted two years later.

All told, in the three-decade span from 1971 to 2001, 18 Black men from baseball’s segregated era, not including players like Robinson and Larry Doby who spent the primes of their careers in Major League Baseball, were invited to join baseball’s most exclusive and prestigious club. But while that group was certainly formidable and deserving, it was also incomplete.

Despite the induction of 40 white managers and executives during this same time period—men like Clark Griffith, Ban Johnson, and, of course, Branch Rickey—only one Black inductee held the same distinction. Rube Foster, who was easily one of the most talented pitchers of his era and also a staunch advocate for player’s rights, was admitted to the Hall in 1981 as a testament to his role in launching the first successful Black league, 1920’s Negro National League.

For Hall of Fame voters, Foster’s legacy loomed as large as his 6-foot-4 frame once did atop the mound. His achievements were undeniable and unassailable, despite Major League Baseball’s eagerness to both deny and assail the efforts of the thousands of men and women who found their own success on their own diamonds.

This is especially the case when talking about Black front-office personnel. Even now, it feels somehow silly to have to say that there could have been no Paige or Gibson, no Black teams or Black leagues, without Black managers and executives. But it does, in fact, need to be said. In baseball and, really, all of professional and collegiate sports, fans readily acknowledge the power of Black bodies, the strength and speed that becomes the foundation of their value to white executives. Much more rarely do we applaud, or even consider, Black intellectual capacity.

Case in point: When Brooklyn Dodgers General Manager Al Campanis was asked about the lack of Black managers and executives in Major League Baseball in April 1987—a question asked by Ted Koppel of ABC’s Nightline to shed light on the league’s (failed) integration efforts a full four decades after Robinson’s debut—Campanis was adamant that Black men belonged in pro sports. He was also clear about the exact positions in which they belonged. “I truly believe that they may not have some of the necessities to be, let’s say, a field manager, or perhaps a general manager,” Campanis said.

Koppel pushed back against the racist assertion that Black people don’t have the mental capacity for certain roles. But when probed, Campanis only doubled down. “How many quarterbacks do you have; how many pitchers do you have that are Black? The same thing applies.”

Perhaps it would have been helpful for Koppel to mention that, before Campanis and Robinson were teammates on the minor league Montreal Royals in 1946, Robinson spent a season in the Negro American League playing for the Kansas City Monarchs. It was there, under the tutelage of the Monarchs’ Black manager Frank Duncan, who led Kansas City to the 1942 Negro World Series title and the NAL pennant in 1946, that Robinson was able to develop into the player who would later be called on to cross Major League Baseball’s still-present color line. This history matters, and Robinson’s own history makes that apparent. While at UCLA, the four-sport athlete batted a paltry .097 in 1940. Easy as it is to marvel at Robinson’s achievements as MLB Rookie of the Year, six-time All-Star, World Series Champion, and, yes, civil rights icon, it seems entirely too easy to forget the role that the Negro Leagues played in kickstarting his ascent.

If Koppel had mentioned this critical detail—and even if Campanis had skirted it—the significance of Black managers and executives in both the Negro Leagues and Major League Baseball’s post-segregation era would have been made explicit. But he didn’t. And the omission of these facts, from Koppel’s interview as well as the wider discourse about baseball history, only illuminates the degree to which the efforts of these men and woman have been forgotten.

This is how baseball fails to acknowledge Gus Greenlee, the Black owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords who was largely responsible for the launch of the second Negro National League in 1933 and who built his own eponymous stadium in Pittsburgh in 1932. We don’t talk about Cum Posey, who, after logging a successful playing career, took ownership of the Homestead Grays, providing the roster and the salary that enabled Gibson and Leonard to heat up the middle of the Grays lineup and hit their way into history books. Neither do we consider Effa Manley, who served as co-owner and business manager of the 1946 Negro World Series champion Newark Eagles, the team that introduced a 22-year-old Larry Doby to an enterprising Bill Veeck and, indeed, the (white) world.

To be clear, this erasure goes beyond a surface-level disrespect of some of the greatest leaders to helm a ball club. When the accomplishments of Black managers and executives are overlooked, it reinforces an antiquated idea that hiring Black people in managerial and executive positions would be a reckless break from some necessarily established norm—that if Black people are to be “allowed” onto the hallowed grounds of Major League Baseball, they would surely be better suited for the field, the setting that best displays their “natural” abilities.

Although Rube Foster’s leadership achievements were recognized in 1981, the Hall continued to exclude his Black contemporaries and predecessors well into the new century, even as white managers and executives continued to collect their own plaques. From 1936 through 2001, a total of 40 white men were inducted not for their on-field prowess but for their in-office savvy; among the Hall’s first four classes (1936-39), 10 of 26 inductees were managers or executives.

This is a history that speaks to the value of leadership, that reveals the reverence baseball reserves for the men who shape and shepherd this sport. And upon closer inspection of who is inducted and who is ignored, these numbers also provide an unmistakable blueprint for who will be allowed to lead baseball now and in the future.

The mantra that Black people are not a monolith is not just an election-cycle cliché; it is a reality, one fully evidenced when news broke that Major League Baseball was officially elevating the Negro Leagues to major league status. For some, including Negro Leagues Baseball Museum President Bob Kendrick, the acknowledgment was long overdue and welcome, the necessary amends for a generations-long slight. For others it was too little too late, little more than a statement of the obvious rendered hollow by MLB’s still-pitiful record on race relations.

As a former employee of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and someone who has spent much of my adult life studying this important history, my thoughts fall somewhere in the middle. No, we didn’t need Commissioner Rob Manfred and his crew to tell us what we already know—that Paige, Gibson, Leonard, and so many others were the best of the best, turning Jim Crow’s barren fields into oases of swagger and skill. We also didn’t need Major League Baseball to tell us that their names should be remembered alongside their white counterparts because, even when the governing rule demanded that baseball remain segregated, Black players were known to take the field with white players and more than hold their own.

Nonetheless, the significance of Major League Baseball’s announcement cannot be overlooked, especially when considering the league’s past views of the Negro Leagues. In his rush to sign Black players from the fall of 1945 through the spring of 1946, Branch Rickey did not consider the Negro Leagues as major league equivalents. As a result, he moved like a plantation owner sweeping into the cabin of his enslaved mistress: covertly but brash, as if whatever he desired was simply his for the taking by right.

With the St. Louis Cardinals, Rickey’s reputation as a game-changing baseball executive was built, in part, on the development of the modern farm system—a system that allowed him to sign players as cheaply possible and then shop them if their talents didn’t fit the club’s needs. Ultimately, Rickey’s expert knowledge of the business of baseball renders his refusal to speak with/compensate Black teams before signing their players all the more egregious, even if Rickey had his own justifications for doing so.

“The Negro organizations in baseball are not leagues, nor, in my opinion, do they have even organization,” he told the New York Times in October of 1945, just days after Robinson’s signing was announced. “As at present administered they are in the nature of a racket.” This opinion directly led to the exploitation of Black baseball and, eventually, to its demise. And because this attack was a direct rebuke of the business and leadership skills of Black baseball executives, it also sullied their reputations and diminished their achievements in the eyes of the entire league.

It’s true that a number of Black owners of Black teams had built their fortunes running numbers operations, an activity deemed illegal until the government decided to get in on the game—and profits—through state-run lotteries. But Rickey never acknowledged the systemic barriers Black men and women faced; he never considered how challenging it was for Black owners to secure cash and keep it flowing while so much of their revenue was funneled to white team owners via stadium rental fees. Instead, Rickey criticized their character; in deriding their lack of bootstraps, he ignored their bootless feet.

So, yes, Major League Baseball’s announcement matters, if for no other reason beyond the fact that it establishes a public denouncement of Rickey’s racist, elitist sentiment. The announcement also declares that, yes, the Negro Leagues were of “major league” status, and that Rickey was wrong for not treating them as such, for not compensating Black teams for their talent, and—perhaps more importantly—for indirectly saying what had always been assumed about Black executives: that their teams, and their efforts, were second-rate.

And these assumptions didn’t just keep deserving Black executives and managers out of the Hall of Fame while their white counterparts were ushered in freely. They created mile-high fences that have kept the would-be successors of Greenlee, Posey, and Manley out of the game altogether.

Of the 17 Black baseball inductees of the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s 2006 class, only five were counted as executives. There were no Black managers from the era inducted—as of this writing, there has never been a Black manager inducted in the Hall—but the occasion was momentous all the same. Finally, more of the people responsible for building the stages on which Black players shined—including Manley, the first woman inducted in the Hall’s history—received overdue recognition. It was an important first step that establishes the capability and credibility of Black executives, a step now solidified by Major League Baseball’s announcement.

It is, however, too early to say whether the “elevation” of the Negro Leagues will amount to anything more than performative lip service.

There have been Black GMs in Major League Baseball since Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers in 1947, re-integrating the majors. But with only five total hires at the GM position since Bill Lucas was tasked with running the Atlanta Braves in 1972, the league’s hiring record for Black executives stands in stark contradiction with its declared commitment to diversity.

And while Kim Ng’s hiring as the general manager of the Miami Marlins fails to move the needle for Black executives in Major League Baseball, her status as the first woman to hold the position could lead to more sweeping measures of inclusivity. Or … it could not. Kenny Williams, who was named GM of the Chicago White Sox in 2000 before being promoted to executive vice president in 2012, has enjoyed a long and successful front-office career. Still, his achievements have thus far failed to open the floodgates for other Black executives. This past offseason, not a single Black candidate was hired to fill one of the eight open GM or President of Baseball Operations positions throughout the league.

Similarly, a celebration of Bianca Smith’s hiring as a coach in the Boston Red Sox’s minor league system—making her the first Black female coach in MLB history—is relatively incomplete without a discussion of Gary Jones and others who saw their careers peak, and stall, in the minors.

These are issues that MLB’s hiring of Ken Griffey Jr., however promising it may be, can’t fix. Even if The Kid is successful in getting more Black kids into the game, as Major League Baseball hopes he will be, those young athletes will still be tasked with navigating a system that has closed its doors to the very people who would be best positioned to nurture and develop them.

The good news is that the act of hiring more Black people in managerial and executive positions isn’t the risk it’s often perceived to be. The history of Black front office success in baseball is as long as Josh Gibson’s tape-measure home runs and as deep as the roster of Effa Manley’s 1946 Newark Eagles—a team that also featured Hall of Famers Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, and Leon Day, and was able to wrest the Negro World Series title from the mighty Kansas City Monarchs.

The history is there; the precedent is there. The only question is whether Major League Baseball will acknowledge it, and whether it will finally give credit—and jobs—where they are most certainly due.

If you liked this blog, please share it! Your referrals help Defector reach new readers, and those new readers always get a few free blogs before encountering our paywall.

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter